On the last day of September, a judge in Georgia struck down the six-week abortion ban that was imposed on the state two years ago, following the Supreme Court’s 2022 decision to overturn Roe v. Wade, the landmark opinion that granted reproductive freedoms to pregnant Americans for fifty years.

Article continues after advertisement

The judge, Fulton Country Superior Court Judge Robert McBurney, called the ban unconstitutional. He wrote: “It is not for a legislator, a judge, or a Commander from The Handmaid’s Tale to tell these women what to do with their bodies during this period when the fetus cannot survive outside the womb.” Absorbing this news (Georgia will appeal the judge’s decision), I thought—as I’ve thought many times this century—about the system of justice that prevailed in another country, in a distant, golden age: the Italian city-state of Siena, seven centuries ago.

The governance of that republic was so fair-minded and so respected that the Sienese people had frescoes made to honor it. The frescoes, painted by Ambrogio Lorenzetti, still can be seen today on the walls of Siena’s city hall, the Palazzo Pubblico. This month, at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, an exhibition opens that showcases art Lorenzetti and his peers made during this flourishing moment in their city’s history: Siena: The Rise of Painting, 1300–1350. But to see Lorenzetti’s frescoes and absorb their civic lesson you must travel to Italy and stand in the room where they are painted. I did so, by accident, many years ago. I have never forgotten.

*

Siena rises from the green and golden-brown hills of Tuscany like a medieval terra cotta mirage. From afar, two tall spikes punctuate the orange-tile roofscape: the licorice-striped campanile (belltower) of the 13th-century Siena Cathedral; and the brick-and-stone Torre del Mangia, the belltower of the palatial city hall.

Long ago, during a work trip to Florence, I took a day trip to Siena with a Tuscan writer friend who was steeped in the city’s lore. He told me that the two belltowers were of equal height, which was a coincidence, but not an accident. During Siena’s Golden Age, in the late 13th and early 14th centuries, he explained, the city was governed by a Council of Nine known as “le Nove” (“the Nine,” in Italian), nine men who ruled over the secular affairs of the populace. The Nine ordered the Torre del Mangia to be built exactly as high as the Duomo’s campanile, as architectural proof that the civic sphere was equally important as the celestial in Siena, under their watch. The era of the Rule of the Nine is known, my friend said, as “the good governance.”

At the time, I paid little attention to my friend’s commentary, and didn’t think much of the strange coincidence that, in modern-day America—as in Siena in the Middle Ages—nine citizens decided the secular fates of their countrymen: the nine justices of the Supreme Court of the United States. My mind that day was not on laws, churches or towers, but on Siena’s fabled biannual horse race, the Palio.

Shortly before my trip, I had fact-checked an intricate, beguiling and enormously long New Yorker article on the history and pageantry of the Palio; and that is what had lured me to the city, even though the race would not be run during my jaunt. I knew that the Palio had taken place for centuries—and that on race days, seventeen riders from the town’s medieval wards (contrade), ride horses bareback at furious pace three times around the cobblestoned Piazza del Campo—Siena’s vast, tilted central square.

I knew (fun fact) that the jockeys use a kind of whip called the “nerbo,” made from the skin of a calf’s penis, to urge their mounts forward. I knew that the Campo’s cobbles are packed with local earth (in shades of “Burnt Sienna” or “Raw Sienna,” Crayola might say) to cushion the track and make it less slippery; but that a horse (or rider) often falls, all the same. And I knew that townspeople flood Siena’s squares and narrow lanes during the Palio to celebrate this tradition, sporting the colors of their contrade, flourishing silken pennants, chanting slogans, and cheering on their jockeys. I wanted to stand in the storied piazza and feel the cobbles underfoot.

The people and scenes depicted reminded me less of the paintings I’d seen in the museums of Florence than of a medieval version of Richard Scarry’s “Busy, Busy World.”

In Siena, my friend left me in the broad, sunny Campo to wander while he raced off to the Duomo, a ten-minute walk away, to buy tickets to climb its stairs, so we could look out on the countryside from on high. He promised to be right back, but it took ages (there was a line). After a while, bored of pacing the impressive but empty square, I walked through the open door of a giant palace that abutted one edge of the Campo, which turned out to be the Palazzo Pubblico, the city hall.

Entering the cavernous main room, the Sala della Pace (Hall of Peace), I felt a thrill of anachronism. Frescoes filled three walls in the kind of wraparound display you might find today at a “Van Gogh: The Immersive Experience” show. The people and scenes depicted reminded me less of the paintings I’d seen in the museums of Florence—of the Madonna and Child and John the Baptist; of The Passion and The Annunciation; and of kings, queens and nobles bedecked in Bronzino greens, Titian reds, and Raphael blues, glinting with jewels, gold and silver—than of a medieval version of Richard Scarry’s “Busy, Busy World.”

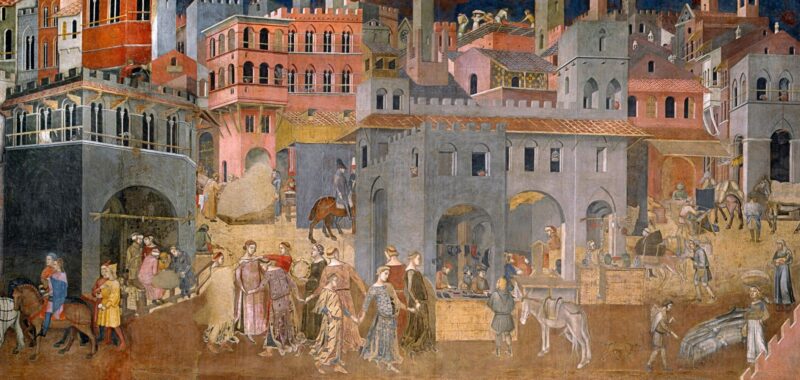

On one wall, smiling Sienese men and women, dressed in ordinary (if antique) fashion, were shown shopping, chatting, dancing, teaching, building, or just hanging out, looking down from apartment windows onto the bustle of the streets below (which resembled the streets I’d seen branching off from the Campo). On the outskirts of town, the fresco showed a merchant leading a pig to market, farmers tending crops, hunters with falcons on their wrists.

The mood struck me as startlingly contemporary. The name of the artist who painted these frescoes, a wall plaque said, was Ambrogio Lorenzetti. Lorenzetti had completed them in 1339, and had died in 1348, presumably of the Black Death (which killed about half of his Sienese contemporaries that year). I had not known, before seeing these frescoes, that a century before Fra Angelico, and decades before the Italian Renaissance, a Sienese artist had made common people his focus, lavishing the detail and respect upon them that Renaissance artists mostly reserved for religious figures and kings.

But this harmonious vision occupied only the east wall. Across the Hall of Peace, it faced another wall that presented a much bleaker portrait of the same city. Here, the townspeople cowered, grimaced and wailed, armed men on horseback rode among them. Scowling men gripped a woman by the arms and led her off; a wounded or murdered citizen lay on the pavement, ignored. Buildings were pocked with artillery holes; the city was under attack; and outside city walls, crops and farmhouses burned. A row of evil leaders presided over this dystopia, chief among them a horned strongman (the label beside him read “Tyranny”) flanked by vicious robed men and women, labeled Avarice, Vainglory, Cruelty and Fraud. At their feet, Justice, personified as a grieving woman, lay tied up, in chains.

Looking down on these dueling urban scenarios from the north wall was the central fresco, which at first glance seemed more Florentine in atmosphere. A godlike man or king sat on a throne, flanked by women of beatific countenance in stately robes. Beneath them, Sienese men and women stood in line, holding a twisted cord that descended from two scales held by an angel on high. The cord passed between their hands until it reached the palm of the godlike man, who held it fast. Like a biblical painting, this fresco clearly held parable; but it evoked Greek and Roman myth, or a Visconti-Sforza tarot card, not the Catechism.

Before the advent of le Nove, in 1285, the city-state of Siena had been riven by wars, feuds, factional divisions, and the predations of what we would call special interests.

Reading more wall text, I learned that the godlike king-man represented the Good Commune of Siena. The “goddesses” embodied virtues like Fortitude, Prudence, Magnanimity and Temperance. One of them, Peace, sat apart from the rest, reclining on a cushion, propped up by silver armor that she didn’t need, since the wise administration of the Good Commune assured harmony in Siena. The “angel” who held the scales (she looked like the Statue of Liberty), was Justice. And the twined cord that passed from her scales to the people represented Concord—equal judgment, equal treatment—descending from the ideal, and shared by the governed, because the Commune secured it.

Lorenzetti’s “The Effect of Bad Governance.”

Lorenzetti’s “The Effect of Bad Governance.”

I learned that these frescoes, collectively, were known as “The Allegory of Good and Bad Government.” The central fresco showed the sought-for ideal of Good Government. The joyful fresco on the east wall showed the Effects of Good Government on the city-state of Siena. The wretched panels on the west wall showed the Effects of Bad Government. What, I wondered, had prompted Lorenzetti’s fixation on justice? And who had commissioned these frescoes, in the 1330s?

I guessed (wrongly) that the frescoes had been intended to warn the (mostly) illiterate citizens of 14th-century Siena, through their richly colored, instructive imagery, that if they did not obey their leaders, they would sabotage their own happiness and security. In other words: if you don’t behave, lawlessness and tyranny will descend upon the land and Siena will be ruined, its women ravished, crops burnt, and everyone’s livelihood destroyed.

But when my friend returned from the cathedral (the tickets to climb the Duomo were sold out), he corrected me. Le Nove had commissioned the paintings, he explained, to warn the rulers not to let down the people. The Nine met in this hall to decide the affairs of the populace; and they entered the room through the door under the main fresco. The Allegory was an admonition, meant to awe the council with the consequences of the decisions they made on the people they governed.

Before the advent of le Nove, in 1285, the city-state of Siena had been riven by wars, feuds, factional divisions, and the predations of what we would call special interests. But for more than sixty years, until the Black Death weakened their hold, le Nove brought Siena unparalleled prosperity, peace and progress through conscientious, public-minded decision-making—which is why the period of their rule came to be known as the Good Governance.

How long, you may ask, did these uniquely effective adjudicators serve—did they have lifetime appointments, like our nine Supreme Court justices? No; but it’s a trick question: le Nove were not appointed, they were chosen by lot; and their terms in office were nowhere near lifetime in length.

They held it as a certainty that members of a group this powerful would face temptations to corruption that some would find irresistible.

So… again: how long was the term of a member of le Nove? Might it have been 18 years—the lengthy span lately proposed by those who wish to reform the American Supreme Court (including President Joe Biden)? No. Perhaps six years, like a US senator; or four years like a president; or two years, like a representative? No. Each member of le Nove served on the council for only two months. Then they were all turfed out, and a new raft selected.

Why, you may ask, did the members of le Nove serve such short terms in office? The answer can be glimpsed in Lorenzetti’s cautionary murals—which surrounded the council members as they made their deliberations, reminding them of their accountability. The Sienese of the Golden Age were realistic, even cynical. Remembering the disorder and injustice of the eras that had preceded theirs, they held it as a certainty that members of a group this powerful would face temptations to corruption that some would find irresistible. They imposed the two-month term limit to protect the public good.

As my friend and I walked out of the Palazzo Pubblico into the sunny Campo, we headed for an espresso bar to talk and to ponder the lesson on the walls. Ducking through a red brick archway, hoping for a shortcut, we found ourselves in a courtyard where three teenage boys were absorbed in a rehearsal for a historic pageant for the next Palio, the Corteo Storico. Two of them knelt at opposite ends of the courtyard, watching each other intently as the third, off to the side, beat a drum. One boy held a long pole topped with a white flag decorated with red and yellow wavy stripes and the emblem of a ram. That meant their contrada was Valdimontone, “Valley of the Ram.”

On an unseen signal, the flagbearer flung the staff high into the air, where it hovered, then looped like a baton before arcing into the waiting hand of his friend. As they executed this skilled, graceful transfer, like their fathers, grandfathers and great-grandfathers had done before them, red dust rose from the cobbles and glinted gold in the afternoon light. I thought then about the tradition of the ideal that le Nove had respected, and that Lorenzetti had translated into art; which still suffused civic life in Siena, some 700 years later.

Our nine do not meet in a room enwrapped in admonitory frescoes; but they do swear an oath to defend the Constitution, which contains the American ideal.

In the last six years, as the composition of America’s nine has changed, taking on a partisan flavor that has undermined public confidence in their judgments (in an Emerson College poll in late August, less than a third of respondents said they thought the court was fair), I’ve thought often of that decades-ago day in Siena, where I absorbed Lorenzetti’s Allegory and happened upon that idyll of community in a courtyard. Again and again I’ve thought of the phenomenon of le Nove, and wondered if there were lessons in Good Governance that this country could take from them.

Our nine do not meet in a room enwrapped in admonitory frescoes; but they do swear an oath to defend the Constitution, which contains the American ideal. There’s no way that a two-month term limit could be imposed on America’s Supreme Court. And yet; the fears of corruption and of abuse of the public trust that led the Sienese powers to constrain their Nove are no less legitimate and pressing today than they were seven centuries ago.

When James Madison was drafting the United States Constitution some 240 years ago, in his upstairs study in Orange, Virginia, he asked his friend and fellow Virginian Thomas Jefferson, who was in Paris as US Minister to France, to buy as many books on “ancient and modern confederations” as he could, and ship them to him at Montpelier. Madison wanted to learn from past precedent what principles were important in creating and preserving a successful republic. Those books, more’s the pity, presumably did not include an art history monograph on Lorenzetti’s Allegory.

To see the Allegory, you would have to travel to Siena—the frescoes are on the walls, after all, not shippable. But seeing the other works created by Lorenzetti and his peers during Siena’s Golden Age may put you in mind of the mission of their art, and of the times that produced it; and of the mission of Good Governance that this country’s council of nine is currently failing.

In the United States today, the nine justices of our Supreme Court are appointed, not selected or elected; and even if they notionally serve the ideal of the Constitution, no code of ethics constrains them from abusing that ideal; and no term limits exist to protect the public from justices who violate it.

On July 1st of this year, the Supreme Court issued a ruling, “Trump v. United States” (supported by six conservative justices; the three liberal justices dissented), which declared that US presidents were “absolutely” immune from prosecution for crimes committed during execution of their “official” presidential duties. The decision has produced an outcry.

That same day, Ruth Marcus wrote in an op-ed titled “God save us from this dishonorable court,” that: “The Supreme Court has just ruled that the president is, in fact, above the law—absolutely immune from criminal prosecution for some conduct and ‘presumptively’ immune for much else.” In an op-ed on July 29th, President Biden proposed three reforms, beginning with a “No One Is Above the Law Amendment” (which would require a two-thirds majority in each house of Congress, plus ratification by 38 states to pass); then term limits (which likely would require a Constitutional amendment to pass); and finally, the creation of an enforceable code of conduct for the nine, which would require a degree of non-partisan cooperation that is unlikely in our polarized congress.

Are our nine above the law? Can you speak of a body as being “above the law” which essentially IS the law—as our nation’s highest court? It sounds positively medieval… except that, as the example of Siena shows, in one city in the Middle Ages, they found a workaround.

What kind of allegory, one wonders, might Lorenzetti paint on the walls of the US Supreme Court, if he were alive today, and got the commission? What would he think of a republic that gave nine men and women the power to decide the fates not of 50,000 people, but of 330 million? And what might he, or any of his fellow citizens, have thought of a republic that empowered those nine to hold sway over their countrymen not for two months, but for a lifetime?