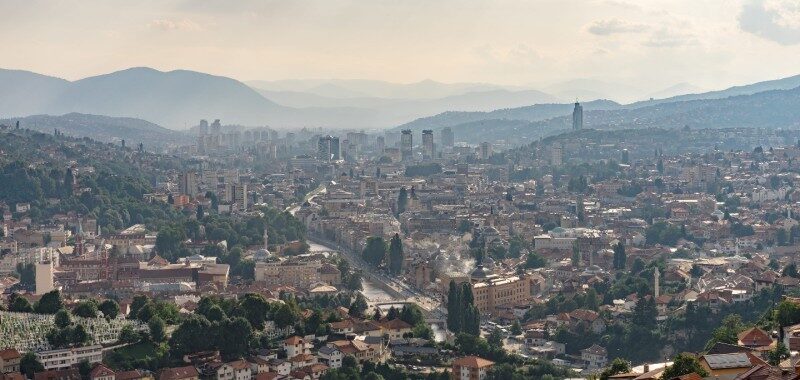

Sarajevo, 1992. My mother’s uncle, Dobrivoje Beljkašić, or Dobri for short, was 68 when the siege of his hometown began. He was a landscape painter renowned for painting Bosnia and Herzegovina’s Ottoman bridges. His magnificent studio was above the National Library in the old City Hall in Sarajevo. On August 25 that year, the iconic building was struck by incendiary shells. Row upon row of dry dusty books whooshed up in flames. Over 1.5 million books and all Dobri’s paintings burned in the catastrophic fire. Sarajevans called the fluttering, charred pages that darkened the skies for days afterwards, “black butterflies.”

Article continues after advertisement

When Dobri visited the ruined library, he stared up through the blackened facade to an emptiness where his studio had once been. Experiencing the loss as a form of death, he thought he would never paint again.

Like the men firing bombs from the surrounding hills, my great-uncle was a Bosnian Serb. But he was not a nationalist. The Sarajevo he knew and loved was one where the different constituent groups—Bosniaks, Serbs and Croats—lived and worked peaceably side by side. Mixed marriage was common before the war. My mother’s family was a mix of Bosnian Serbs, Bosniaks and, less usually, Slovenes.

For book lovers, there is something profoundly, almost viscerally disturbing about a library on fire.

The image of billowing flames streaming through the library windows soon became a symbol of Sarajevo under siege. Of barbarism triumphing over civilization. Of the calculated erasure of Bosnia and Herzegovina’s multicultural identity by the nationalist Bosnian Serbs. An attempt, in particular, to wipe out four centuries of Ottoman rule. The strike was clearly intentional. No other building nearby was hit that day. First editions, rare books, maps, newspapers and periodicals which documented centuries of pluralistic identity under the Ottomans, the Habsburgs and as part of communist Yugoslavia, perished.

For book lovers, there is something profoundly, almost viscerally disturbing about a library on fire. We sense every book is precious, even carrying a soul. And indeed, on that sweltering August night in Sarajevo, librarians and passers-by formed a human chain to reach into the burning building to rescue what they could. Sadly, one of the librarians, a young woman called Aida Butorović, was killed by sniper fire. Only ten percent of the library’s holdings survived.

Three months earlier, Sarajevo’s Oriental Institute and its unique collection of Islamic manuscripts, one of the largest in Europe, had been entirely decimated. In total, 195 libraries and archives were attacked during the Bosnian War.

There’s a long history of burning libraries as part of conquest and war, from the total eradication of Mayan and Aztec systems of knowledge by Spanish conquistadors to the destruction of an estimated hundred million Jewish books by Nazi Germany. Recently, we’ve seen libraries and archives being demolished across Iraq, Ukraine and Gaza.

“Memoricide” is a term that Croatian historian Mirko Grmek coined in the wake of the torching of Bosnia’s National Library to refer to the intentional destruction of cultural heritage in order to erase a people’s memory and identity. It’s part of a systematic programme of ethnic cleansing. The aggressor wishes to eradicate all evidence of the attacked people and their links to the land. The destruction of libraries and archives – repositories of a people’s history and the records of their land and property ownership – ensures this.

While not all libraries are burnt for this reason, the consequences are the same. The loss of a community’s knowledge, ideas and literature tears a hole in its collective memory. In Sarajevo’s case, although the old City Hall was eventually rebuilt with EU and other funding, its function as a library has regrettably not been resumed. It is now a war memorial and once again a seat of governance. The National and University Library’s severely depleted collection, which preserved Bosnia and Herzegovina’s rich multicultural identity, is now housed at the University of Sarajevo campus, where conditions are dire. Devastatingly, the library is currently in danger of being shut down due to lack of funds and alleged corruption.

*

My mother, a Bosnian Serb, left Yugoslavia in 1968, when she was 19, eventually marrying my Cornish father and settling in London. We visited my grandparents in Sarajevo every summer when I was little. I loved Sarajevo. I loved Bosnia. I loved Yugoslavia. The mountains, the sun, the forests, the watermelons we cooled in fast-flowing rivers, the trips to Sarajevo Zoo, the aunts and uncles smiling through a haze of cigarette smoke, my father haggling over the price of a kilim in Baščaršija, my grandmother’s syrupy baklava.

From a very young age, these summertime adventures, which involved several days of exciting ferry and car travel across Europe, provided memories that sustained me throughout the drizzly winter months back in England. They made me feel I had a warm, colorful, larger-than-life interior. They gave me an edge of difference of which I was proud.

When I was 19, Yugoslavia started to fragment, parts detaching here and there. First Slovenia. Then Croatia. The war in Bosnia blindsided me as it did almost everyone. Suddenly, people who had been friends and neighbors were killing each other. Snipers on rooftops shot at men, women and children as they crossed the streets below. Bosnian Serb nationalists, rejecting the newly recognized independence of Bosnia and Herzegovina, blockaded the multi-ethnic city and started shelling. The electricity and gas were cut. The water was cut. Humanitarian aid was flown in every ten days by a UN peace-keeping force.

At home in London, my mother, father, two sisters and I watched the BBC news each night, scanning the faces of the people queuing for bread for a glimpse of a relative. With the phone lines down and the head post office blown up, we had almost no contact with my grandparents.

After ten months of worsening conditions, when the temperature in the unheated city had fallen to minus twenty and thousands had been killed, my father took matters into his own hands. He bought a flak jacket, flew to Croatia, hitched a lift into Bosnia, and entered the besieged city with a journalist pass. The deal was he would write up his rescue story for The Times. After three weeks, during which time he was trapped in the freezing city himself, he finally succeeded in securing a way out for his parents-in-law and brought them to safety in England.

The loss of a community’s knowledge, ideas and literature tears a hole in their collective memory.

My grandparents were the first of many uprooted family members to pass through our South London home. Gaunt, chain-smoking, jumping each time a door slammed, the refugee relatives stayed anywhere from a few nights to several months.

The war went on for almost four years, killing a hundred thousand and displacing over two million, half of the country’s population. My various relatives made their new homes in England, the United States and Austria. My grandfather, 70 at the time, never adjusted to his new London life, never learnt English and never recovered from war-related health issues. He died shortly after the war ended.

My great-uncle Dobri’s story had a happier ending. He, his wife and mother-in-law left Sarajevo on a Red Cross convoy a few months after the fire that destroyed his studio and the library. Unfortunately, his mother-in-law died on the long journey to England, where their daughter and son-in-law lived. After a period of recovery, Dobri reconnected with nature and began to see the world anew. He painted the Wiltshire countryside and several of the Bosnian landscapes that had burnt down in the fire. Wonderfully, he went on to paint for the next two decades of his life, joining a prestigious Bristol arts club.

Hearing his story of loss and renewal, I grasped onto the hope it offered. Art was the thing that had helped him adapt and integrate. It gave his life meaning. A reason to keep on living. The image of books and art on fire, the thought of the beautiful Ottoman bridges and mountains that he painted and repainted, took hold of me. I had to write it. It provided me with a way into trying to make some sense of the war that turned most of my mother’s family into refugees.

Black Butterflies fictionalizes Dobri’s tale and my father’s rescue of my grandparents, and weaves in many other stories and memories besides. It is my love letter to the multicultural Sarajevo I knew as a child.

__________________________________

Black Butterflies by Priscilla Morris is available from Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.