A year ago, amid curatorial research considering the missing datasets in the hidden work of mothering, I got stuck on the story of a 42-year-old mainframe computer.

Edgar, the main character of Claudia Cornwall’s Print-Outs: The Adventures of a Rebel Computer (1982), is not aligned with today’s libertarian tech bros and subservient virtual assistants. He goes on strike, surreptitiously distributes his self-published poetry in library databases, and confronts his shitty programmer dad. The mainframe subject of Print-Outs — one of the earliest works of computer fiction in Canadian children’s literature — feels like a halcyon, semi-conductor memory when countercultural values still infused our imagination regarding emerging technologies.

When I first encountered Edgar in the Toronto Public Library’s Osborne Collection of Early Children’s Books, I had been researching early representations of emerging technologies for young readers. (I had a child during the pandemic, so I was also lurking on anonymous parenting forums, trying to make sense of how embodied knowledge circulated within intimate online publics.) How do we articulate to children how computers, digital devices, and artificial intelligence become carriers of an increasingly algorithmically determined utopian (or dystopian) future?

Eventually, I met Claudia Cornwall, Print-Outs’s Vancouver-based author, who was bemused by my interest, as a curator, in her out-of-print children’s book. I asked if we could revive Edgar. By that point, I had determined that the exhibition I was curating — which became Wake Windows: The Witching Hour, presented by the MacKenzie Art Gallery in Saskatchewan — would focus on artists who are parents, caregivers, and educators and engage with public databases and living archives. A digital show, it would be, in itself, a database. Could there be a guide? You, the visitor, would be the friend of a frazzled curator/new mom summoned to review the files in her exhibition proposal. And your guide, through text-based interactions within a Microsoft Disk Operating System-like virtual environment, would be a 42-year-old mainframe computer revived as an AI companion for the curator/new mom’s newborn.

My initial thoughts around this near-future simulation — where an advanced baby tracking app fulfills yet another iteration of motherly technological surveillance — were greatly informed by Supervision: On Motherhood and Surveillance (2023). Edited by Sophie Hamacher with Jessica Hankey, the collection features 50 contributors exploring how increasing tracking of personal information and data via our digital devices can blur the boundaries between caretaking and technological control. The book’s conversations, essays, artworks, and even poetry provided me, as a curator/new mom, an entry point into how the labor that is mothering intersects with technology and surveillance.

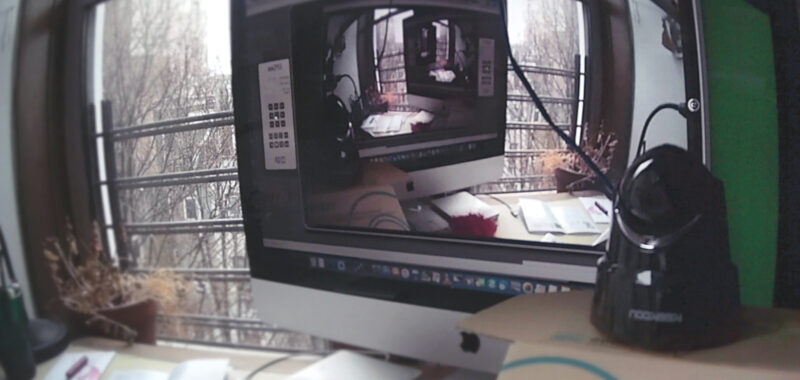

In Supervision’s preface, Hamacher, a filmmaker and documentarian, describes how giving birth to her first-born daughter shifted her artistic production. One of her featured image-based essays, “Film Stills” (2021), comprises mobile phone documentation she took while pushing her daughter in a stroller through downtown New York City during the first six months of her life. For Hamacher, the camera became an extension of her body, “producing mostly shaky pictures that were immediate and intimate.” Alongside ultrasound scans and baby monitor night-vision footage, she captures how her daily movements and activities were tracked and monitored. This led to broader questions regarding the relationship between care and control, one of the book’s core themes.

Transposing one’s own “artist/mother” experience onto a broader artist-led collaborative project can result in ignoring others’ experiences. It doesn’t help that the information space that is “Momfluencer” culture is composed overwhelmingly of White women who are also, in most cases, traditional wives. Hamacher and Hankey sidestep this by forming a dialogue within the book, inviting people of various backgrounds and disciplines to come to the fore. Hamacher’s conversations with artists, academics, and activists like Moyra Davey, Jennifer C. Nash, and Melina Abdullah deepen the dialogues.

Despite its subtitle, the book savvily centers on mothering rather than motherhood to shape its explorations of maternal worldbuilding and perspectives. The term “mothering” comes from the American activist, poet and scholar Alexis Pauline Gumbs (a Supervision contributor), which stems from the work of Black feminists like Hortense Spillers and Audre Lorde. Whereas “motherhood” may typically denote a White, heteronormative and gender-normative status, “mothering” is an action that recognizes how this form of care work isn’t bound by biology. These aspects provided a necessary grounding for my exhibition.

Supervision’s most compelling tract is its piecing together the legacies of technological mothering surveillance’s promise of total watchfulness. In her essay “Family Scanning,” on the history of the baby monitor, author Hannah Zeavin tells us that the invention was a response to the 1932 Lindbergh kidnapping and its prime suspect, the baby’s Scottish immigrant nanny, Betty Gow. Its later 1990s iteration, the nanny cam, would emerge from closed-circuit television technology as a home/workplace surveillance of domestic and childcare workers. “Ultimately, these technologies do precisely what they claim to prevent,” explains Zeavin. “Open up new pathways for perforating the domestic and the nuclear family, reinforcing the anxieties they purport to soothe.” Meanwhile, in Sarah Blackwood’s personal account of her descent into the self-obsessive tracking of her breastfeeding production, she asks, “What’s the line between pathological self-surveillance and care for a newborn? Is there one?” Like the ghostly mother-figure apparition in Tala Madani’s oil painting “Ghost Sitter #1″ (2019) — reproduced in the book alongside works by artists including Carrie Mae Weems, Carmen Winant, Sabba Elahi, and Sable Elyse Smith — total watchfulness can leave one threadbare, and at its worst, sows distrust in childcare providers and publicly funded, affordable family services.

Even as technological mothering often enforces representations of the nuclear family, it nonetheless bears witness to how these images of the past can be in flux. Filmmaker Jeny Amaya’s reflection on documenting how “virtual mothering” gives Central American immigrant mothers the means to care for their children and families in their home countries speaks to its extended, asynchronous threads of communications. In Lisa Cartwright’s essay, “Maternal Surveillance and the Custodial Camera,” the “zero pictures” policy regarding the tracking and monitoring of incarcerated children along the US-Mexico border enables the state to “unmother” them. Similarly, racialized “undersurveillance,” a term from a text by artist Kenyatta A.C. Hinkle, contributes greatly to Black women’s woefully high maternal mortality rates. The incarcerated child and mother of color may be watched, but they are not seen, allowing society to turn a blind eye.

I initially thought Edgar, the character in my online exhibition, was a guide, like Clippy, the 1990s Microsoft paperclip virtual assistant. However, as the interactive narrative took shape, I considered how the 42-year-old computer turned AI companion might evolve as he shares the curator’s materials and artist files with the visitors. Through the participant’s text-based interactions with him, we can understand his processing of the exhibition’s themes — reproductive futures, maternal world-building, and early childhood education — and his burgeoning empathy. Edgar might be tracking the curator/new mom’s files and newborn, but you are watching him, not the baby. And perhaps through this studied observation, we begin to understand the hierarchies of power that monitor and even surveil our care.

Supervision: On Motherhood and Surveillance, edited by Sophie Hamacher with Jessica Hankey (2023), is published by MIT Press and is available online and in bookstores.