The Prodigal Converses with the Land

Article continues after advertisement

I

Cape Coast:

I am a city in translation. What I say to you is not in the language

I carry. You will never understand the pidgin of my soil

because you, poet, are always a foreigner. It is true

that your grandmother’s bones are interred in me,

and I know you hoped that by returning to me

you would hear her speaking. But you must know

that even more desperate people have come,

asking for some sound to carry through.

At least you know that I was named by white people,

and they have left the noise of atrocities here,

so that when those who come back, year after year,

instead of speaking of the drama of the ocean

beating against the shore, instead of the shouts and songs

of the fishermen dragging their catch across the dark sand

for the women to collect and take to the market, instead

of the clubs, the hi-life, the scent of bread baking at night,

instead of the deep forests that reach the edge

of the sea, and the way the sunset falls over Elmina,

instead of this, all they can talk of are the ones

who were collected here and taken across the waters,

only to return as interlopers, people with foreign tongues,

who do not understand our language of centuries.

We are the Akan. We are warriors, the broken companies

of the Oguaa. This means nothing to you. What you know

is the smell of soap and algae in the gutters, and the way the brine

in the lagoons thickens in the air; the addiction to akara

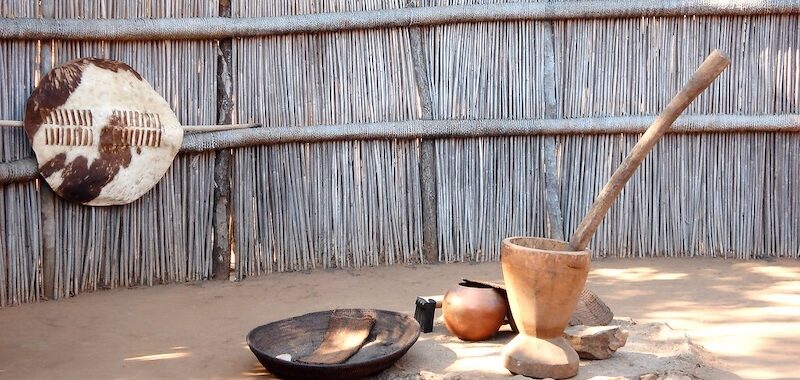

and the tart heat of pepper; and the tom-ba, tom-ba

of the mortar and pestle, the familiar sounds of heart and hearth:

these are the things that you will talk about, places

of nostalgia, of home. But all places know themselves

by the blood that has been shed there, the sadness

that will always haunt the laughter of this place.

Here is that church where your Mammy, the Pentecostal woman,

found her own Jesus, saw the coil of a python on the heavy shoulder

of her daughter, your mother, and they cast out the demon curse

on her, freed her from what would have consumed her.

She was young then, the age of your youngest

daughter. But she remembers, Chochoo remembers.

II

Kwame:

I know that the invention of memory, the silence before memory

is made—

the imagined comfort of language, though failing every time,

though betraying my inner head and liver—is what I have,

is what we all carry. I lied when I said I found

the translation of this land into something like a nation,

or home, or comfort, or the spirits of ancestors—

I lied, and still I will say to you who stand at the gates

of this village, “Tell Mammy her grandson,

the one she teased, tell her he is asking to be let in,

and he is craving her fresh baked bread.”

______________________________

Reprinted from Sturge Town: Poems by Kwame Dawes. First published in Great Britain in 2023 by Peepal Tree Press Ltd. Copyright © 2023 by Kwame Dawes. Used with permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.