“Life is a bitter aspic.”

–Wallace Stevens

*Article continues after advertisement

“Stir-fried pork and asparagus is a starting point for poetry.”

–Zhang Di (trans. Eleanor Goodman)

*

First, I am obsessed with aspic. The word is gelatinous. I want to eat it—the word, that is. As for the dish, mostly I gaze at images of it. In one photograph, translucent jelly traps within its radiance precision cuts of carrot, zucchini, and quail egg; the lime green plate on which it sits turns the aspic a little yellow. In another, the jelly acquires an orange glow from the gemmed centers of cherry tomatoes encased within. Aspic’s the jewelry of food, I think.

I think of aspic as the reverse-madeleine. If the material for Proust’s seven-volume novel were said to have sprung from savoring a single madeleine dipped in tea, perhaps aspic is memory—or whatever it is one seeks to grasp—held in abeyance, trapped in jelly. It is a thing I know is there. I am able to study its contours, smell it, touch it, discern its colors and layers; I can know it to an appreciable extent without eating it. You can’t say this of soup or even a tiered cake.

I suppose this is why I haven’t yet tried to eat aspic. It’s sexier withheld.

Incidentally, the madeleine too is a molded comestible. It’s a small sponge cake shaped like a shell. It does well dipped in tea. The famed madeleine episode that occurs early in the first volume of In Search of Lost Time is often paraphrased as an event of comical speed: the protagonist tastes the tea-soaked madeleine; poof!; we get four thousand pages of remembered narrative.

Actually, the process is quite methodical. First, he tastes a spoonful of tea in which the madeleine has soaked: a “delicious pleasure” invades him. He drinks a second mouthful, then a third, with diminishing returns. In between that first sip and the moment the first—the instigating—memory finally arrives are nearly three pages of the protagonist trying and trying again to unearth the source of that sudden “delicious pleasure.”

If the material for Proust’s seven-volume novel were said to have sprung from savoring a single madeleine dipped in tea, perhaps aspic is memory held in abeyance, trapped in jelly.

Some relevant excerpts (translated by Lydia Davis):

I put down the cup and turn to my mind….I ask my mind to make another effort, to bring back once more the sensation that is slipping away….Then for a second time I create an empty space before it, I confront it again with the still recent taste of that first mouthful….Ten times I must begin again, lean down toward it.

This strikes me as a dogged method of inquiry inaugurated and sustained by taste.

Though I continue to maintain a gustative distance from aspic, I believe quite strongly in eating as a form of research. Eating can be an entrance into thought and action, though at other moments it’s a happy fall into oblivion (“Indeed eating is so pleasant one should even try to suppress thought,” observes Iris Murdoch’s Charles Arrowby in The Sea, The Sea).

It’s the kind of research that led me to write a series of forty or so brief meditations on food called “Concerning Matters Culinary.” Here’s one:

THERE IS DEATH FOLDED

IN MY MOUSSE TODAY

Here’s another:

SEASONED THE WINE

MULLED THE PARADOX

NOW PERPLEXED SOLUTIONS

TRICKLE INTO MY CUP

The series appears at the heart of my new book of poems Material Witness, out from Nightboat Books.

*

First, I am obsessed with aspic. Then, I want to know who invented it and how and why. I search for its first appearance in a cookbook. I also begin to wonder what the first cookbook is.

Chief among the contenders is a compilation of Ancient Roman recipes called De re coquinaria, which translates to something like “About Culinary Things.” That word re is the ablative case of res, which one might recognize from res ipsa loquitur (“the thing speaks for itself”) or in medias res (“in the midst of things”). Aside from “thing,” res can mean ?cause,” “event,” “fact,” “property,” and “matter.”

I enjoy a word like res that denotes primarily abstractions—concept things, things of the mind—but lurking somewhere in its semantic realm is a tangible thing thing. A culinary matter is a food-related topic or question; it could also just be an ingredient or tool for cooking. A culinary matter is abstract and concrete both. My preferred translation of the Latin cookbook therefore is “Concerning Matters Culinary”; I make it the title of my culinary serial poem.

It appears that for a long time the compilation of De re coquinaria was ascribed to one Marcus Gavius Apicius, an infamous gourmet who lived in the first century C.E.. Seven of its recipes are named after him (one of which could be a precursor to aspic from well before the Middle Ages; more on this bit of wishful thinking soon).

But Sally Grainger—chef, food historian, and (in my opinion) leading expert on this book—posits that it was primarily the work of enslaved cooks, unnamed and highly skilled laborers responsible for feeding the ruling elite to which Apicius belonged.

Grainger calls De re coquinaria a “practical handbook, a ‘blue-collar’ text” and explains that it is written in Vulgar Latin, the language of the home, the street, and the workplace. Its lack of measurements and sparse directions frustrate me as I’m sure they would others, but the culinary professionals of the time would have known what to do with them.

Then there are those intrepid historians and translators of the contemporary era who have sought to figure the dishes out. One might credit—or blame—a certain Joseph Dommers Vehling for the few years I spent believing Ancient Romans were eating aspic on a regular basis, or you know, at all. Vehling’s was the first English translation of De re coquinaria I encountered; it was first published in the 1930s.

Vehling translates two dishes—one “Sala Cattabia” and the other “Aliter Sala Cattabia Apiciana”—as respectively “Boiled Dinner” and “Apician Jelly.” While the meaning of sala cattabia is evidently up for debate, aliter just means “another” and Apiciana, “in the style of Apicius.”

The recipes are clearly variants of each other: both involve grinding together ingredients for a dressing or sauce, followed by assembling various ingredients in a pot and drenching them in “[a lukewarm, congealing]” or “[jellified] BROTH”; in the final step, the pot is placed in ice or snow to set before being unmolded and served.

Why is one variant merely a boiled dinner and the other a fanciful jelly? Perhaps the name Apicius—the suggestion that he himself might have updated the humble dinner—imbues the latter with incumbent glory. It’s more likely that Apicius became associated with the dish simply because he liked the second version better. Its ingredients do sound rather special: “PICENTIAN BREAD” instead of the regular kind; a special cheese from the Adriatic coast; and sweetbreads.

What I can’t figure out is why Vehling understood the poured-over liquid to be a broth, let alone one that was “[congealing]” or “[jellified].” As the brackets indicate, that word doesn’t appear in the Latin text.

My quite modest facility with Latin gleans something like “pour the liquid” (ius perfundes) in the first recipe and “pour the liquid on top” (ius supra perfundes) in the second.The index in Vehling’s edition lists the verb gelo (“to freeze or congeal”) and the noun gelu (“jelly”), suggesting that jellification was a known technique of the time.

But this indexical entry isn’t linked to either of the sala cattabias. (Actually, there is a third such dish and Vehling seems to have given up finding an English name for it; it’s just “OTHER SALACACCABIA.”)

Meanwhile, Christopher Grocock and Sally Grainger—who have prepared the most recent critical edition of De re coquinaria—interpret all three “Sala Cattabia” dishes as salads rather than jellies or boiled dinners. They note that “[a]ll the ingredients that would normally need cooking, such as the meat, are assumed to have been prepared in advance.” While they agree the dishes must be molded or layered somehow, they translate the ius in both cases as a sauce to be poured over, presumably the viscous mixture made of herbs, honey, and vinegar (among other items) in the first step.

Grainger has also produced a handy little trade paperback called Cooking Apicius: Roman Recipes for Today for layfolk who might want to try their hand at Ancient Roman cuisine in an approachable way. She provides measurements and substitutes for hard-to-source ingredients. Her adapted version of “Sala Cattabia” is basically chicken (liver) salad—a slightly unusual one that includes bread, cheese, cucumber, capers, and pine kernels with a “creamy mint sauce poured over.”

Creamy mint sauce, jellified broth—these differences in interpretation sound dramatic, but I find them fascinating, dexterous, savvy. I’m fascinated by them in the way I am by variant translations of non-recipe texts.

Translating and cooking both involve transformative acts of reading and remaking. It’s poesis, pure and simple. Cooking—particularly at home—requires one to make do with whatever is at hand: ingredients in the refrigerator, produce easily available in local stores, items one can afford to buy.

It’s the same with translation: one makes do with the target language’s possibilities and constraints, sometimes squeezing the most out of it in order to recreate a particular effect from the source text. And sometimes you’re very happy with what you squeezed out of it.

(Apropos: the chili plants I’ve been growing in an attempt to maintain a steady supply of the kind of green pepper I need most for Indian cooking continue to produce flavorful but sadly mild fruit. I’ve started to let them turn red on the plant, which makes the chilis hotter and more floral-tasting. The resulting curries are a bit different from what I grew up with, and I enjoy them for that very difference.)

I translated some of these Ancient Roman recipes—on a couple of occasions with a treasured reading group—mostly to improve my Latin. But translation’s effects tend to be somewhat extra. Something about having to feel my way into a practical text whose language was nevertheless opaque to me, opaque but steadily acquiring translucence as I worked my way through, made language feel even more visceral. Like matter itself, a thing thing.

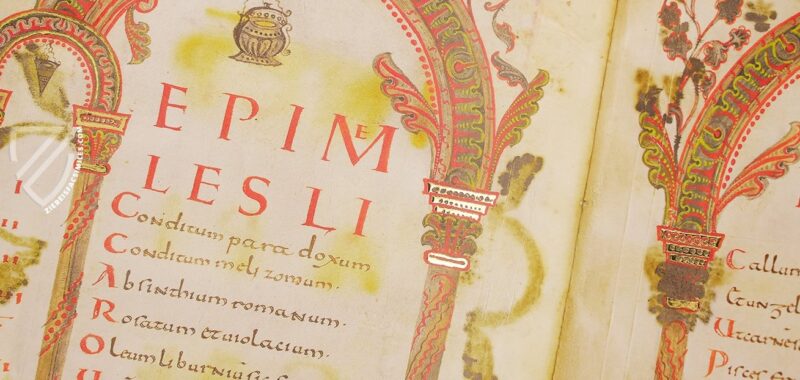

My first clumsy stab at translating a recipe in De re coquinaria had me parsing its title “Conditum Paradoxum” as “Spiced or Savory Paradox.” An abstraction infused with sensation, an opacity turning translucent, a word giving off fumes! Imagine the “delicious pleasure” this gave me!

I had relied upon the verb condire (to season, spice, or make savory) to achieve my translation. Turns out the phrase is a much more mundane: conditum refers to a family of spiced wines and paradoxum can mean something like “special” or “surprising.”

Poetically, “Incredible Spiced Wine” doesn’t do it for me the way “Spiced Paradox” does. A spiced paradox enfolds me in its contradiction; it seasons my thinking, invites me to reflect on how and why I have become infused.

In the end, I failed at discovering the source of aspic but (re)discovered translation as cooking, eating as meditation, and cooking as a preparation for thought and action.

In the end, I failed at discovering the source of aspic but (re)discovered translation as cooking, eating as meditation, and cooking as a preparation for thought and action. Each process involves the radical transformation of matter, a transformation one might elect to slow all the way down and observe in the flux of its happening.

I suppose in writing my poetic version of “Concerning Matters Culinary” I was recording transformations of edible matter—as it ripens, wilts, or decays; as it gets cooked, eaten, and digested—in poetic language. At first the record took the form of weird little recipes (a salad of kohlrabi ribbons, tender coconut, and salted juniper berries); then the poems became meditative, even a little funny.

But even the funny ones are deadly serious. As in, there is death folded in my food today and every day. I ought to remember that.

______________________________

Material Witness by Aditi Machado is available via Nightboat Books.