After Kansas City’s victory in the recent Super Bowl, an X post in the wake of tight end Travis Kelce’s highly publicized embrace of Taylor Swift, his girlfriend, went viral. In it, the user alleged that a “televangelist from Arkansas” stated that Swift’s likely marriage to the football pro was orchestrated so that she could give birth to the Antichrist and launch the apocalyptic thousand-year war against Christ. The claim is notably unsubstantiated, and the name of the televangelist in question has not been offered up. However, the allegation is just one in a flood of right-wing conspiracy theories that continue to envelop the pop star.

There is little doubt that the broad public appeal and measured liberal leanings of Taylor Swift have many conservatives worried about her possible role in the upcoming US presidential election. A new poll from Monmouth University indicates that around 18% of the American public now believes she is part of a covert plan to re-elect President Joe Biden. But allegations of Satanic worship are not a new contention for her. Swifties know that Reddit theorists and White evangelicals have long maintained that the singer has ties to the Church of Satan. This is partially due to her striking likeness to Zeena Schreck, the daughter of the Church of Satan’s co-founders.

Such allegations against Swift have grown to a fever pitch in the leadup to a contentious and high-stakes election. And yet these apocalyptic allegations feel both desperate and sadly familiar. Since antiquity, periods of political uncertainty and religious anxiety have often generated spurious proclamations of the Antichrist, false allegations of satanic worship, and warnings about the imminent Apocalypse.

Instead of addressing the probability of Swift and Kelce giving birth to the Antichrist, let’s start with some basics. For one, what even is the Antichrist? The Biblical figure’s name literally means “opposed to Christ.” Today, American Evangelicals in particular believe he is foretold to rule before the Last Judgment as an agent of Satan. He is mentioned only five times in the New Testament, all in the epistle of 1 John. Each time the Antichrist is directly or indirectly referenced, as in the “man of lawlessness” noted in 2 Thessalonians, it is without a proper name or secure identifier. What we do know is that the Antichrist is a false prophet necessary to trigger the second coming of Christ and the subsequent Battle of Armageddon.

The Antichrist has also been falsely identified numerous times over the last 2,000 years.

Perhaps one of the earliest named Antichrist figures was the Roman emperor Nero. Nero Claudius Caesar ruled from 54 to 68 CE and was known for his cruelty. Often remembered as the alleged instigator of the first Christian persecution following the Great Fire of Rome in 64 CE, Nero was only later named the Antichrist by early Christian writers, centuries after his death. From academic research to museum exhibitions, scholars and institutions are now reassessing the accusations leveled against the heavily maligned imperator.

The British Museum is one such institution, with an exhibition titled Nero: The Man Behind the Myth that ran from May until October 2021 at its London galleries. The Nero exhibition was an attempt to use contemporary artifacts to clarify the myths and misconceptions surrounding the Julio-Claudian emperor. Encompassing around 200 objects from across the Roman Empire, the show aimed to recast Nero as a man of the people. The tyrant rumored to have played the fiddle as the Great Fire of Rome burned, the curators argued, was actually a misunderstood populist beholden to the desires of the Roman public. In fact, the fiddle hadn’t even been invented when Nero was supposed to have played it.

As it turns out, it wasn’t just the fiddle that was an anachronism. The Roman historian Tacitus remarked that Nero blamed the devastating conflagration on a small, emerging religious sect within the city only later called Christians. However, in The Myth of Persecution (2013), historian Candida Moss notes that Nero’s pinning of the fire on Christians may only be a story fabricated by Tacitus himself. Princeton University historian Brent Shaw made a similar argument in an article in the Journal of Roman Studies blaming Tacitus for pinpointing Christians as the group scapegoated for the fire. It may be that Nero is not the man to blame, after all. Perhaps it was Tacitus and, later, the early Christians themselves who used Nero as a tool for their own purposes.

Among some Christian theologians in the later Roman Empire, Nero then developed into the figure of the Antichrist, thus becoming fundamental to early Christian identity formation. Particularly in the early 3rd century, the idea that Nero might be the Antichrist and had blamed Christians for the Great Fire became increasingly important in filling in many of the ambiguities within the Thessalonians, the Book of Revelation, and other visions of the impending Apocalypse, such as the earlier Book of Daniel. Nero seemed to fit the bill in particular because there were rumors that he actually had not died in 68 CE by assisted suicide, and continued to live. In addition, he fit nicely into the apocalyptic sea beast in Revelation (later interpreted as the Antichrist) with seven heads — each head being a king.

To help the 4th- and 5th-century faithfuls envision the perfect Christian, theologians of the era proposed a model antithetical to the ideal: Nero. New research from Shushma Malik has lifted the veil on how later Christians developed the idea of the Antichrist and associated Nero with the end times in the late Roman Empire and then again beginning in the 19th century. Her 2020 book also investigates something the British Museum largely did not: how reception — that is, the later referencing and rewriting of history — refashioned Nero as the Antichrist.

Into the Middle Ages, the identity of the Antichrist changed frequently depending on the political climate. Accusations were often thrown at monarchs, popes, and potentates during times of crisis and upheaval. Allegations also enshrined contemporary ideas of the “other.” The 7th-century Spanish bishop Isidore of Seville believed the Antichrist came from outside the Church — heretics, Jews, and possibly Muslims. In fact, the Prophet Muhammad was frequently cited as the Antichrist. The 10th-century Benedictine abbot Adso of Montier-en-Der, who wrote a popular biography of the Antichrist, claimed the figure would be Jewish, underscoring the deep antisemitic sentiment among many Christians in the Middle Ages.

But when did the Antichrist first appear depicted as a human in art, not just an apocalyptic beast? Art historian Rosemary Muir Wright pinpointed this initial illustration within a Spanish manuscript created between 930 and 950 CE. The artwork accompanied an earlier book called Commentary on the Apocalypse by a monk named Beatus of Liébana who lived in the Asturian region of Spain in the 8th century CE. Numerical tables often accompanying these popular manuscripts allowed readers to assign numbers to the letters in the name of Antichrists and add them up to the number of the beast referenced in Revelation: 666 (DCLXVI).

Women also figured in fleshing out the life story of the Antichrist. A 12th-century German abbess named Hildegard of Bingen had apocalyptic visions in which she specifically saw the birth of the Antichrist coming from within the Church, rather than the competing narrative of the Antichrist as Jewish. Hildegard warned of corruption within the Church and the connection to the Antichrist. She became quite the celebrity in her own time and went on regular speaking tours, discussing the corruption in the Church with both men and women.

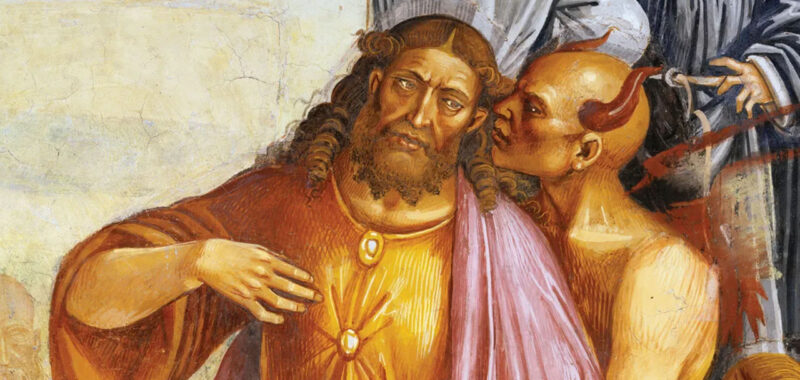

During the late Middle Ages, Christian scholars promoted the idea of multiple antichrists before the main Antichrist would emerge. Claims of antichrists also positioned one group, Christians, as a savior of humanity within a divinely ordained plan. As medievalist Michael Ryan has argued, by the end of the Middle Ages and into the Renaissance, clerics and then Protestants also wielded the Antichrist as a rhetorical tool to call for institutional reform within the papacy and the Church. In the Italian city of Orvieto, the Renaissance artist Luca Signorelli would paint the hugely influential work “The Sermon and Deeds of the Antichrist” (1499–1502) in the Chapel of San Brizio in the midst of economic and social upheaval in the city, as well as rainstorms, plague, and other ominous signs that might portend the end times.

In 1520, German theologian and Protestant Reformation leader Martin Luther began to believe that the papacy was itself the Antichrist. Luther saw himself as the antidote in the long-prophesied final struggle between good and evil. By the 16th century, invoking the Apocalypse could also be used to justify ideas of a manifest destiny during the Age of Discovery. Reinterpreting the Book of Revelation to justify his own actions was integral to Christopher Columbus’s outlook, as well. In 1500, he proclaimed, “God made me the messenger of the new heaven and the new earth of which he spoke in the Apocalypse of St. John after having spoke of it through the mouth of Isaiah; and he showed me the spot where to find it.” As theologian Maria Leppäkari has shown, Columbus quoted apocalyptic literature to the likes of King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella of Spain. The monarchs and Columbus himself hoped that exploration of the New World would bring enough gold to reclaim Jerusalem for Christianity.

Accused antichrists often reflect the social conditions and interests of their times. But contextualizing their naming goes beyond recognizing the accusation merely as a societal mirror. Instances of named antichrists can reveal not only a common Christian vocabulary for describing excessive evil but oftentimes also a desire to see themselves as the hero of a crisis — and to present themselves as true believers in opposition to the Antichrist.

If we look further toward the 19th century, we see many alleged antichrists emerging, from literature to “scholarly” attacks on Catholicism and new interpretations of Revelation. In Leo Tolstoy’s novel War and Peace (1869), the story opens with a Russian woman of the court named Anna Pavlovna Scherer at a soiree set in 1805. She rants that then-Emperor of France Napoleon Bonaparte was an Antichrist, and later, another character finds Masonic writing decoding the fact that Napoleon was tied to the sign of the Beast.

As Russianist Michael Pesenson has discussed, this anecdote is just a portion of a larger apocalyptic discourse in Russia during the early 1800s. Russian apocalyptic views cast Napoleon as the Antichrist and, in turn, made Russia the rescuer of the world. For every Antichrist, there is someone who casts themselves as the fated savior leading the march toward Christ’s return. As in Roman antiquity, for every anti-hero, there must be a hero.

And what of American Christianity’s obsession with being the one to correctly pinpoint the identity of this Antichrist? Five years before the apocalyptic prophecies that populated the media leading up to the year 2000, historian Robert Fuller published Naming the Antichrist: The History of an American Obsession. In it, he traced the idea of the Antichrist from antiquity to the founding of the United States, noting how early colonists cast Native Americans in the Antichrist role, as well as Catholics. Fuller then moved into the 20th century, when then-President Franklin Delano Roosevelt was accused of being a pawn of the Antichrist, falling in line with the actions of Hitler, Mussolini, and Stalin.

The Ku Klux Klan also capitalized on eschatological imagery and the fear surrounding the Apocalypse as one way of validating and legitimizing their violent campaigns against Jews, Catholics, and African Americans. In 1925, a White woman named Alma Bridwell White published a popular book called The Ku Klux Klan in Prophecy, which included illustrations of key apocalyptic episodes and created a direct link between the Klan, the prophecies of the Bible and the Book of Revelation, and American patriotism.

Notions of the Antichrist rooted in antisemitism and anti-Blackness have not dissipated in the 21st century. In 2012, Southern Baptist pastor Robert Jeffress claimed that a vote for Barack Obama paved the way for the Antichrist. Subsequently, a 2013 poll noted that one in four Americans believed Obama might be the Antichrist. Hillary Clinton then became one of the rare women to be named as an Antichrist. And yet, we cannot shrug off men like Jeffress with a dismissive laugh. The influential pastor later became a close friend of Donald Trump and spoke frequently about how access to the president had allowed evangelical Christians unprecedented political sway via the White House. Many Christian evangelicals in the United States believe not only that the end times are near, but that they have a duty to reveal the truth behind its coming. Faith in the evangelical role as “true” revealers of God’s ultimate plan and their part in unmasking the false messiah is also one reason why conspiracy theorist groups like Q-Anon have attracted so many White evangelicals.

Although some might mock and dismiss white nationalist conspiracies, claims of the impending end times are neither marginal nor benign in today’s America. Scholars of religion like Anthea Butler and Kelly Baker have already revealed an undeniable intersection between apocalyptic thinking and white nationalism. Such beliefs are also behind many fundamentalist and evangelical notions supporting the state of Israel. A 2018 study found that over half of evangelicals believe Israel’s existence is needed — and should be defended politically and economically — as a part of fulfilling God’s larger plan for the end times, consequently influencing right-wing political movements.

New Testament scholar Gary Burge has noted how Christian Zionists in particular often support Jews not out of a sense of camaraderie or kindness, but as a means of setting into motion the ultimate plan for Christ’s return to Earth and to “accelerate an eschatological crisis that will deliver the world to Armageddon and bring Christ back.” At a Wisconsin rally in 2020, Trump tacitly remarked on his earlier reasons for moving the US embassy to Jerusalem from Tel Aviv by saying, “And we moved the capital of Israel to Jerusalem. That’s for the evangelicals.” Evangelicals eagerly greeted Trump’s recognition of Jerusalem as a move that set into motion the constellation of events that would lead to the final battle of good and evil.

Whether Nero, medieval Jews, the Pope, or Taylor Swift, revisiting alleged Antichrists across history can unveil the motivations behind accusations formulated in periods of crisis and uncertainty. Reconstructing the long history of accusations of antichrists also brings the millennia-long Christian obsession with the Apocalypse into focus, while throwing into relief the ways in which religious leaders use apocalypticism to political ends.

Within America today, eschatological beliefs have already reframed the war in Ukraine — especially for evangelical and fundamentalist leaders. In 2022, aging televangelist Pat Robertson noted that Russian President Vladimir Putin was “compelled by God” to invade Ukraine. Robertson connected the war with the road that would lead to the eventual Battle of Armageddon. Quoting the Prophet Ezekiel, Robertson returned to a familiar adage: What seems to be chaos is, in fact, a part of God’s plan. To him, the invasion of Ukraine could then be understood as the fulfillment of a long-foretold prophecy, one that benefits evangelical Christians in particular. And he is not speaking to a minority of people. Later that year, the Pew Research Center released a study that said that 39% of Americans believed they were living in the end times.

Taylor Swift may be a self-professed “anti-hero,” but if history is any indicator, the practice of naming Antichrists will only continue. The ambiguity of Christian Apocalypse narratives in scripture and in later tellings has long created space for opportunists. Periods of “Satanic Panic” and endless warnings about the coming end times have a long and troubled history, but not one we should so easily dismiss as marginal or impotent. Religious leaders, white nationalists, and politicians have long capitalized on threats of evil and charges of Satanic meddling to persuade those living — and voting — in the present. Swift, her boyfriend, and even her close friends have become the target of satanic slander in large part because she is a wealthy woman under her own control and one who, without a doubt, could use her popularity to sway the 2024 election.