In 2015, artist Matthew Chavez was recovering from a motorbike accident that left him in the hospital for three weeks and unable to walk for months when he planted the seeds for Subway Therapy, a public participatory art project that has become a phenomenon across the Metropolitan Transit Authority (MTA) system.

“I thought a lot about how grateful I was for my family and my friends that showed up for me,” Chavez said in an interview with Hyperallergic. “I thought: You know what? I want to show up for people that don’t have that in New York.”

That Christmas Day, Chavez said set out to become the “New York Secret Keeper,” asking strangers to confess a secret with him to lighten the burden of holding it.

“As a stranger, it wouldn’t be so heavy for me, but I’d help them carry the weight,” Chavez said.

Soon after launching his secret-sharing campaign, Chavez — who is not a licensed counselor — said he began holding mock therapy sessions, setting up a mobile “office” in subway stations complete with wall art one might find in a private practice and two chairs where Chavez and participants would enact therapeutic confessionals.

Subway Therapy gained prominence in November 2016, when Donald Trump secured the White House for the first time. Chavez incorporated sticky notes into the performance, taking the project out of the artist’s hands and into the hands of the thousands of people who ride the subway each day.

This month, Chavez recreated the project during the week of November 7, capturing a rare glimpse into the thoughts of New Yorkers following the election.

At the height of the project’s post-election popularity in 2016, disgraced former Governor Andrew Cuomo left a note of his own: “New York State holds the torch high! – Andrew C.” Strangers left messages including “Trump is inhumane,” “Love to my Muslim brothers and sisters,” angry sentiments toward the electoral college, and the popular slogan “Love Trumps Hate.”

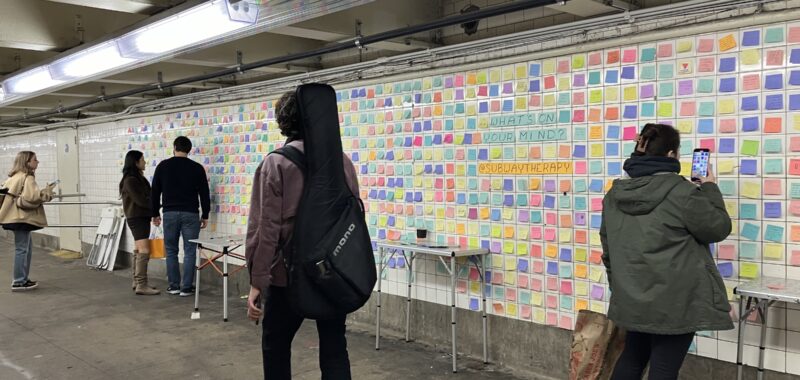

Eight years later, the rhetoric hanging from the neon Post-it squares is different. While there was barely any room for even one more sticky note at the Union Square station in 2016, this year’s confessionals are more sparsely populated, and their messages seem less reactive to a Trump win.

Chavez set up a shop between November 5 and 10 in an underpass at the 14th Street subway complex with a prompt spelled out in tacked notes: “What’s on your mind?”

Scribbled messages from this month included calls to action like “Free all innocent Black men and women,” “Love and Protect Trans People,” “Free Cuba,” and “Democrat or Republican, they both send billions to Israel, ditch the bread and circuses.” More common than overtly political statements in this year’s crop of notes, however, were participants’ witty personal observations.

In English, Spanish, and French, passersby contributed intimate thoughts to the public wall, perhaps indicating an ambivalence to this year’s election. “Gracias New York por permitirme conocer al chico de mis sueños,” one note written in cursive read. (“Thanks New York for letting me meet the boy of my dreams.”)

Others wrote “Just had an amazing date,” “The price of a coffee is wild [sic] expensive,” “This wall is vibrating it makes me cry,” “Brat,” “I miss my family and boyfriend,” and “Quiero Taco Bell.” Other notes shared cancer diagnoses, grief for lost parents, and mental health struggles.

Chavez attributes the difference in the messages to a change in this year’s prompt. “In the past, I’ve done ‘Express yourself for the election,’” Chavez said. An observation that has remained steady over the years, he explained, is the persistent need for public expression among New Yorkers.

Chavez has also started his own nonprofit, Listening Lab, which hosts events and workshops on listening and “community development.” Now he manages Subway Therapy via the organization and sends volunteers underground for the project’s subway pop-ups at stations including Columbus Circle and Union Square.

“One thing that is so ever-present is how much people need opportunities to express themselves in shared space,” Chavez said. “There’s this huge divide, this big chasm between people who are experiencing the same thing.”