Augusta Savage played a pivotal role in the Harlem Renaissance as a sculptor and teacher who opened doors and held them open for other Black artists. But despite her wide reach and countless accolades, only a small portion of her crucially important artwork has been preserved for future generations to learn from and enjoy. A new short documentary from Audacious Women Productions, hosted by art historian and curator of Augusta Savage: Renaissance Woman (2018–19) Jeffreen M. Hayes and free to stream on PBS, examines and celebrates Savage’s legacy while questioning how so much of it was allowed to vanish over time.

“Searching for Augusta Savage” (2023), the 22-minute first installment of PBS’s new American Masters documentary shorts, tells the story of a steadfast woman who persisted in her artistic goals despite the obstacles before her. Hayes sets the scene by introducing one of Savage’s most important projects, “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” a 16-foot-tall plaster sculpture commissioned for the 1939 World’s Fair in Flushing, New York, which honors African-American music through the portrayal of an arm raising 12 Black singers into the air to create the silhouette of a harp.

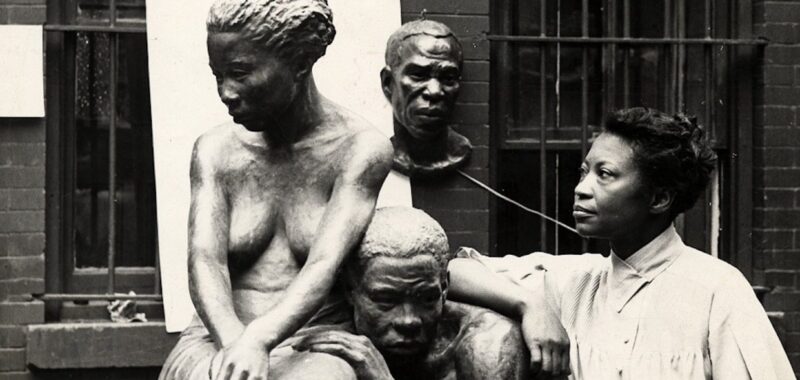

Savage’s commission was demolished after the fair ended, as she didn’t have the funds to preserve it. Aside from photo documentation, all that’s left is a small maquette of the piece. Indeed, the majority of her sculptures and monumental achievements have been reduced to mere memories. Savage’s sensitive and dignified portrait busts, primarily of Black subjects, were typically sculpted from plaster or clay, as she couldn’t afford to cast them in bronze. As a result, many of her artworks couldn’t be preserved, or otherwise remain unaccounted for.

This lack of access is unfortunately still ongoing. “The issues that Augusta Savage navigated in her time, and the impact they had on the visibility surrounding her legacy, are problems that Black artists are still dealing with in the present day,” Hayes told Hyperallergic. “These are issues of visibility, of discrimination, of racial inequality, of financial limitation, and of sociocultural barriers. During Savage’s life and since, she faced sexism along with racism and what we call today misogynoir — the intersection of racism and misogyny that exists against Black women, specifically at the hands of Black men.”

Through her childhood as the seventh of 14 siblings; her education at Cooper Union, which she completed in three years despite working to support her family; and her opening a free community art school as well as a gallery dedicated to African American art, Savage always made a point of not only standing out, but going above and beyond to deliver in her own name and for her communities.

But she was unable to withstand the financial burdens of her teaching and gallery endeavors at a time when there were so many financial and social limitations imposed on Black women, and eventually left the city.

In the film, Hayes explores Savage’s 1945 move upstate to Saugerties and the life she built for herself along the Hudson River, in which she was cherished by her neighbors, visited by her friends, and freely writing and creating.

Though much of her work has been lost to time, her legacy persists, and is taking new forms. Students like Jacob Lawrence, Gwendolyn Knight, and Norman Lewis, among others, remember her fondly and cite her as a critical resource. Savage’s home and studio are on the National Register of Historic Places, and current overseers are looking to host a visual or literary arts residency to continue the artist’s lifelong commitment to nurturing the creatives of the next generation.

“Savage left behind a blueprint of what it means to be an artist who centers humanity, community, and advocacy. She was committed as a sculptor to depicting Black people in the most beautiful way,” Hayes told Hyperallergic. “But she also passed down knowledge of how to create art to those who did not otherwise have the means. She paved the way for artists, curators and arts leaders to be community-builders and institution-builders.”

In the documentary, Hayes delves into Savage’s remaining correspondence. “I have created nothing really beautiful, really lasting,” Savage wrote in 1935. “But if I can inspire one of these youngsters to develop the talent I know they possess, then my monument will be in their work.”

In honor of Savage’s leap-day birthday, the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture collaborated with the New York Public Library’s Digital Imaging Services and its Center for Educators and Schools to develop an educational kit for teachers across the city.