This first appeared in Lit Hub’s Craft of Writing newsletter—sign up here.

Article continues after advertisement

My wife and I have a strange habit. Whenever one of us needs to accuse the other of causing harm, we yell “J’accuse!”– the French phrase which grew to fame from Émile Zola’s open letter published during the Dreyfus affair. The words are always accompanied by a dramatic upstroke of a sharply pointed index finger.

It’s highly effective.

The simple phrase forces burgeoning disputes into the open and establishes a tenuous perimeter around our conflicts in a manner not dissimilar from the firefighter’s controlled burn.

Beyond marital disputes, accusatory moments hold tremendous power to build narrative momentum. But in a world drowning in wrongdoing, and subsequently, accusations of wrongdoing, the narrative power of “the accusatory moment” is easily overlooked. But writers ignore the power of the accusatory moment at their mortal peril.

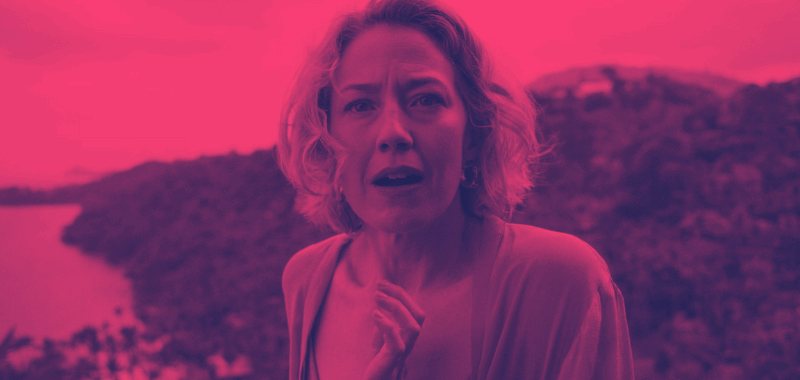

Okay, maybe not “mortal.” And maybe not “peril.” But Season 3 of The White Lotus is a textbook example of how accusations are narrative momentum machines. Whether you think that Season 3 is the best or worst of the loti is beside the point. The point is that a record six million viewers felt compelled to finish the season. And it may be useful to understand the mechanics of why.

Before we journey to that luxury Thai resort, first, a brief heart-to-heart with the conceptual uncle of the accusatory moment: “the request moment.” The latter term coined by the revered novelist, poet, and essayist Charles Baxter. Baxter argues that request moments are dramatically useful because they 1) happen in a social world with social consequences, 2) may reveal power relationships, and 3) expose ethical obligations. Not all stories need request moments, but some stories go flat because the request hasn’t been clarified.

Accusatory moments carry with them implicit requests, so these two kinds of moments create overlapping effects. Apologize! Stop being awful! Make this better! These are common parenthetical requests of accusations, often loud and unsaid at the same time. Both accusations and requests demand immediate action and may reveal and shift power dynamics. They tell us what people do and think they can do under the grip of such forces. And both contain a generally finite number of responses for the viewer or reader to guess at (yes, no, maybe, ignore) which create a gamified story experience, promoting engagement and simplifying the value landscape, as noted by philosopher C. Thi Nguyen.

That said, accusatory moments offer the potential for additional layers of narrative urgency through our desire to know: 1) the self-judgment of the accusee, 2) the distance between that self-judgement and the accusee’s response, and 3) the ways in which the accuser processes and responds to that response.

Accusatory moments are the heartbeat of all three seasons of The White Lotus, perhaps none more so than Season 3. All three seasons generate narrative momentum by building up the stakes around multiple synchronous and interconnected accusations. The key storylines that commandeer viewer curiosity often orbit the question of how one character will respond to an accusation by another. In Season 3, these accusations cluster in episodes five through seven, driving urgency in a sprint toward the finale.

Unlike requests, which social graces may permit us to politely decline in ways that return us to the original state of a relationship, the same cannot be said of accusations. There is no going back.

In episode five, Belinda, the visiting spa manager from Maui, escalates her accusation that the wealthy expat “Gary” is actually Greg, who may have killed his wife, and she raises her concerns with Fabian, the general manager of the hotel. One key distinguishing feature of accusations is they almost always bring along not only requests but also the other two general categories of imperatives identified by Baxter: advice and commands. In Belinda’s case: Hey Fabian, you should call the police! American, Italian, Thai—call all the police! These added layers of imperative raise the stakes of Fabian’s response giving a dismissal of the accusation greater weight. Which is exactly what we get. Fabian dismisses Belinda faster than Carrie Coon hightailing it away from gunfire. But the aftermath of an accusation does even more to rev the narrative engine. Accusations irrevocably alter the connection between accuser (Belinda), accusee (Greg), and witness (Fabian). Unlike requests, which social graces may permit us to politely decline in ways that return us to the original state of a relationship, the same cannot be said of accusations. There is no going back.

Another distinct feature of accusatory moments is they often create an exponential impact less typical of other imperatives by generating escalating and retaliatory accusations. We see this most clearly with the girlfriend trio: with Laurie’s accusation that Jaclyn had an affair with staff health mentor Valentin. When both Jaclyn and Kate try to brush off the significance of Jaclyn’s hook-up, Laurie escalates the accusation, claiming Jaclyn did the same thing with Kate’s husband Dave. Jaclyn finally retaliates, accusing Laurie of never being happy with her life. That her unhappiness is a choice she does to herself—the short stick she always chooses. Kate immediately piles on: “The source of your disappointment changes, but the constant is you’re always disappointed.” Having arrived at this point of no return, Laurie fires everything she has left. To Kate—”You’re always fake and fronting like your life is perfect.” To Jaclyn—”And you’re vain and selfish.” Having said the worst things about her friends she can say, Laurie has no choice but to go make questionable life choices at a Muay Thai fight. The downstream effects of a single accusation can be staggering.

That there is no going back after an accusation should have been clear to Rick, our existentially tortured likely criminal, who concludes the penultimate episode in the series with our final major accusation: that the owner of the White Lotus, Jim Hollinger, killed his father. But instead, Rick almost acts as if episode seven hadn’t occurred. Briefly cleansed of his long-held burden and cradled by a false sense of closure, he returns for a delightful breakfast with his girlfriend, Chelsea, at the resort belonging to the accused.

You can’t do that Rick! You made the accusation. You can’t go back!

Jim Hollinger’s arrival shortly thereafter leading to the violent climax of the season finale, and its Darth Vaderesque (Rick, I am your father) moment, makes that much abundantly clear.

These are only a few of many accusatory moments floating throughout The White Lotus universe that drive narrative momentum. Beyond that universe, so many compelling recent novels convey urgency by leveraging the power of accusations: The Vanishing Half by Brit Bennett, Leave the World Behind by Rumaan Alam, Chain-Gang All-Stars by Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah, The Guest by Emma Cline, Intermezzo by Sally Rooney. Fiction is well-poised to exploit the power of accusatory moments because of its unparalleled access to the interiority and self-judgment of the accused and the ways in which time can be manipulated on the page to interrogate evolving power dynamics with exquisite nuance.

If only the same were possible in my marital life.