Linguists Find Proof of Sweeping Language Pattern Once Deemed a ‘Hoax’

Inuit languages really do have many words for snow, linguists found—and other languages have conceptual specialties, too, potentially revealing what a culture values

In 1884 the anthropologist Franz Boas returned from Baffin Island with a discovery that would kick off decades of linguistic wrangling: by his count, the local Inuit language had four words for snow, suggesting a link between language and physical environment. A great game of telephone inflated the number until, in 1984, the New York Times published an editorial claiming the Inuit have “100 synonyms” for the frozen white stuff we lump under a single term.

Boas’s observation had swelled to mythic proportions. In a 1991 essay, British linguist Geoff Pullum called these claims a “hoax,” citing the work of linguist Laura Martin, who tracked the misinformation’s evolution. He likened it to the xenomorph from Alien, a creature that “seemed to spring up everywhere once it got loose on the spaceship, and was very difficult to kill.” His acerbic critique rendered the subject taboo for a generation, says Victor Mair, an expert on Chinese language at the University of Pennsylvania. But now, he says, “it’s coming back in a legitimate way.”

In a sweeping new computational analysis of world languages, researchers not only confirmed the emphasis on snow in the Inuit language Inuktitut but also uncovered many similar patterns: what snow is to the Inuit, lava is to Samoans and oatmeal to Scots. The results were published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA in April. Charles Kemp, a computational psychologist at the University of Melbourne in Australia and senior author of the study, says the results offer a window onto language speakers’ culture. “It’s a way to get a sense of the ‘chief interests of a people’—what’s important to a society, what they prioritize and value,” he says, quoting Boas.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

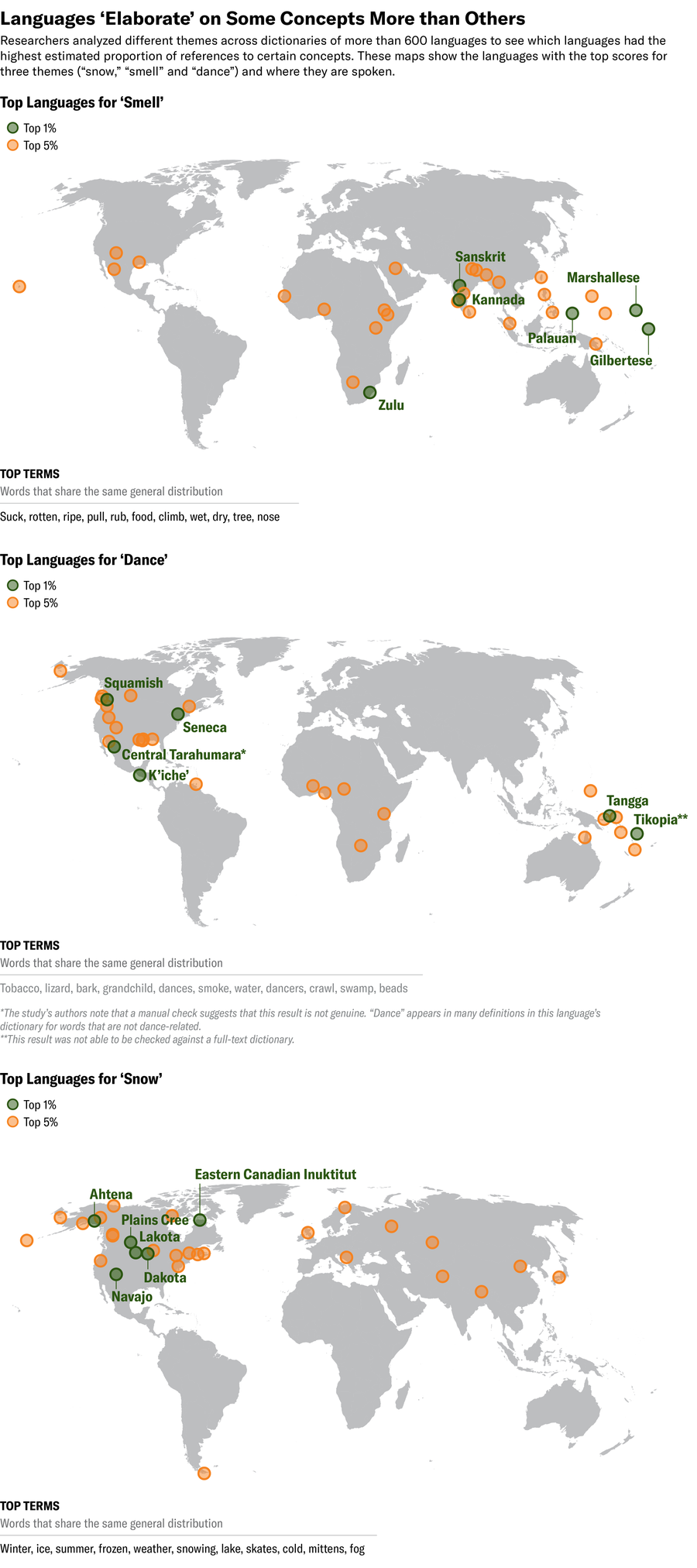

The researchers analyzed bilingual dictionaries between English and more than 600 languages, looking for what they call “lexical elaboration,” in which a language has many words related to a core concept. It’s the same phenomenon that fueled the Inuit debate. But this study brings a twist: rather than the number of words, it measured their proportion, the slice of dictionary real estate taken up by a concept. This produced elaboration scores for hundreds of concepts, from “abandonment” to “zoo,” based on how many times the English words for those concepts appeared in the definitions of foreign words. You can explore the results in this online module that shows which languages have the most words for each concept and which concepts have the most words in each language.

Ripley Cleghorn; Source: “A computational analysis of lexical elaboration across languages,” by Temuulen Khishigsuren et al., in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, Vol. 122, No. 15; April 15, 2025

Often the elaboration is clearly a product of environment—small wonder that Arabic, Farsi and Indigenous Australian languages abound with words to describe the desert, and Sanskrit, Tamil and Thai with words for elephants. Other cases aren’t so straightforward. Many Oceanic languages, for example, have highly specific words for smell. In Marshallese, meļļā means “smell of blood” and jatbo means “smell of damp clothing.” This may be explained by the humidity of the rainforest, which amplifies scents. But why is the concept of rapture so prominent in Portuguese and agony in Hindi? What historical and cultural circumstances lead a language down such obscure paths? “I’m not sure if anybody knows,” Kemp says.

Mair says this research, which he highlighted on the popular linguistics blog Language Log, helps resurrect the much-maligned idea of linguistic relativity, sometimes known as the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis. At its boldest, linguistic relativity asserts that language determines how we perceive things, causing speakers of different languages to experience the world in radically different ways (think of the movie Arrival, in which a character becomes clairvoyant after learning an alien language). But in Mair’s opinion, this study supports a softer claim: our brains all share the same basic machinery for perceiving the world, which language can subtly affect but not restrict. “It doesn’t determine,” he says. “It influences.”

Similarly, Lynne Murphy, a linguist at the University of Sussex in England, who was not involved in this study, notes that “any language should be able to talk about anything.” We may not have the Marshallese word jatbo, but four words of English do the trick—“smell of damp clothing.” It’s not that having many precise words for smell reveals mind-blowing cognitive abilities for processing smell; it’s simply that single words are more efficient than phrases, so they tend to represent common subjects of discussion, highlighting areas of cultural significance. If we routinely needed to talk about the smell of damp clothing, we’d whittle that unwieldy phrase down to something like jatbo.

Still, “lexical elaboration alone cannot tell us about the culture of its speakers,” at least not with certainty, says study lead author Temuulen Khishigsuren, a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Melbourne. And because this analysis was based on dictionaries, it comes with the biases and limitations of the lexicographers that wrote them. As Murphy puts it, they “offer only snapshots of a language at a particular time, from a particular angle.” Some of the dictionaries used are decades or centuries old, and they may reflect the archaic concerns of colonizers—to translate the Bible or establish a trade route—as much as those of modern-day speakers. Dictionaries of vast written languages like German or Sanskrit are much larger than those for languages that are exclusively spoken and are loaded with esoteric terminology.

Because dictionaries don’t represent how people use language in the real world, the next step would be to measure how often people actually talk or write about the concepts being studied, such as snow and smells and elephants. This is difficult for languages without large bodies of written text but could be possible for many languages, especially those used heavily on social media.

It bears remembering that these lexical elaborations come from comparison between languages—French only has “many” words for futility because other languages have fewer. And because all the bilingual dictionaries in this study map back to English—it’s the language into which everything else gets translated—the analysis is influenced by the words used in English itself. If we find the patterns of elaboration in other languages unusual, it’s safe to assume their speakers will return the favor. “English is as ‘different’ as any other language,” Murphy says, which raises the question: “If we had started from, say, Spanish or Chinese or Malayalam, which concepts would have stood out for English?”