There is a trove of items you’re prohibited from carrying in your purse or luggage over the US border. Some of these are: dog and cat fur, Haitian goat hide drums, soil from your Lagos backyard, African elephant ivory, terracotta statues from Mali, icons from Cyprus, Khmer stone archaeological sculpture from Cambodia, and perhaps most important to the Japa terranaut, the immigrant, select food articles.

Article continues after advertisement

Rice, chestnut cowpeas, melon seeds, achi, snails, periwinkles, kenke, African star apples, ugba, fura, are slowly plucked out of immigrants’ bags by CBP officials tasked with preventing the admission of agricultural pests into America, and tossed carefully into plastic-wrapped trash cans while the defeated traveler swallows hard, wondering if this is after all the opportunity cost of seeking a life in the United States. Many immigrants—like the stranded characters in T.C. Boyle’s The Terranauts—spend the rest of their lives in the US resigned to a fate in which they’re cut off from delicacies they’d enjoyed eating in their mothers’ kitchens in places as far away as Lusaka or Asuncion, for the simple reason that these items are unavailable at Walmart or Kroger.

This inaccessibility often triggers feelings of isolation, and a kind of aggressive rootlessness. It could also precipitate the loss of one’s mother tongue—already atrophied from limited use—because food can act as a receptacle of memory and language, drawing one back into early childhood and its shaping force, and the associative jargon of those recollections, allowing the immigrant not only to roll the syllables naming these foods on their tongues in a kind of remedial ritual, but also to evoke a connection to a language that now floats outside of its natural landscape.

Food can act as a receptacle of memory and language, drawing one back into early childhood.

The kind of slow, inquiring research that figures out the existence of a food-language ecosystem doesn’t appear to be top-shelf concern for multilinguists or cognitive psychologists today. But there exists some related study, conducted by neuroscientists at West Virginia University, which shows how breastfeeding stimulates language acquisition in babies. The longer infants are breastfed, the researchers say, the more connective strength they show in certain parts of the brain concerned with language performance. Anthropologists also believe that our specie’s leap forward into the development of language was possibly stimulated by our forebears’ change of grub. Though this theory highlights how a calorie increase pumped up our brain size and mediated our ability to originate language, one cannot overlook the curious link it draws between food and language.

Five years ago, a group of research-scientists (from Lyon, Zurich, Singapore) in collaboration with the Max Planck Institute, announced to the world that our ability to pronounce “f” and “v” sounds is a recent development in our evolution, induced by how diet changed the shape of our teeth. And in 1985, the linguist, Charles Hockett, noted that “f” and “v” sounds had been prominent in agricultural societies because they ate softer meals. Those sounds were not produced in hunter-gatherer communities who generally cracked hard nuts between their teeth and tore tough meat off bones. Further evidence that food can give breath to language.

Whenever I’ve attended African parties here in the US, cheesy Afrobeat, polite chatter, and teeth-flashing laughter have been the prologue to food. It’s often struck me as a minor anthropological miracle when folks promptly slip from English into Yoruba, or Igbo, or Twi, after the first spoonful of jollof rice, or the first pinch of banku. This same marvel reenacts when immigrants stroll into African, Asian, or Hispanic grocery stores and see all the food they aren’t allowed to bring in on display. That voluntary loss of English for something more forgiving, more sheltering. More Proustian. These stores function as sites of language retrieval, retention, and identity boosting.

Food is the scaffolding on which language builds reality.

Jacques Lacan, the French psychoanalyst, famously placed language above reality. Language, he argued, creates the world. And if anthropologists are to be trusted, and if immigrant social behavior—in the United States—at least from a subjective perspective, is to be cast in perpetual spotlight, then food is the scaffolding on which language builds reality.

I do not know how ethnic food stores get their products over the US border, but I suspect there is a system of compromises in place for provisions that arrive in commercial quantities. Perhaps storeowners are advised: bring in none of A, we’ll greenlight B. I’m inclined to ride with this premise because months ago my family purchased a bag of periwinkles at an African store in Atlanta only to realize all the shells were empty when we reached our final stop in Mississippi. Obviously we were swindled, but I wonder if the storeowner, knowing he couldn’t import those spiny ocean creatures and some other forbidden item (say, smoked fish) at the same time, decided to haul in deshelled winkles he intended to sell for the real thing—knowing that wouldn’t count to CBP—as a tradeoff for the smoked fish.

I still remember the Igbo word for snail, eju, but can no longer recall what a periwinkle is called. I have a vague memory of watching steam rise from a heap of boiled periwinkles in my mother’s kitchen, and hearing her tell me its name in Igbo as I plucked out one gray shell and weighed it in my palm. I’m quite certain the name will return the minute I crush the electric-green, rubber-soft flesh of a winkle between my teeth. One Japa day.

__________________________________

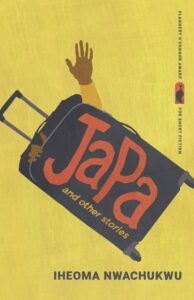

Japa and Other Stories by Iheoma Nwachukwu is available from University of Georgia Press.