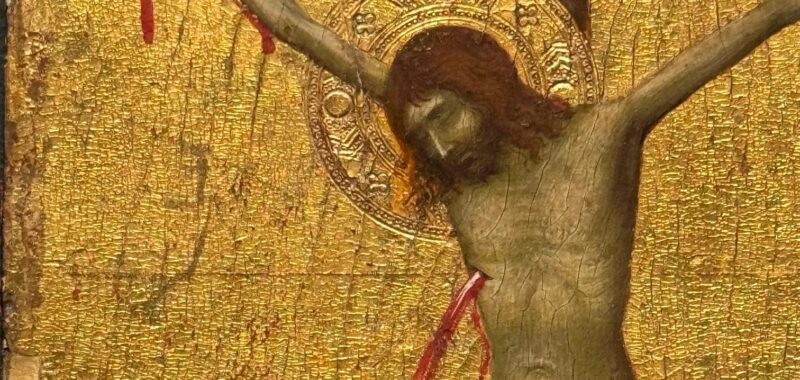

Siena: The Rise of Painting, 1300–1350, an examination of Siena’s breathtaking mix of blood and gold at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, is long overdue. Works like Simone Martini’s “Christ on the Cross” (1340) simultaneously glow and ooze in a dramatic contrast. The show rightly avoids the bias toward Florence in early Renaissance narratives that unfold in most museums and art history curricula outside of Italy. However, recent trailblazing research is missing in the show’s didactics and left underdeveloped in the catalog. A changing contemplative theology of flesh led by friars throughout Italy created the underlying market conditions for Sienese artists to imbue their figures with more dimensionality and emotion alongside the scintillating expanses of gold.

St. Dominic (1170–1221), portrayed in the iconic Duccio triptych on loan from London’s National Gallery, and St. Francis (1181–1226) inaugurated movements that would not only revolutionize Christianity from within but also change the direction of art history. After the meteoric rise of their namesake mendicant orders in the 13th and 14th centuries, Dominican and Franciscan friars began to demand new forms from devotional art. This prompted a dramatic paradigm shift that the friars led as patrons, as their novel theologies and meditative practices contributed to the iconic “fleshy breakthrough” in late 13th- and 14th-century Italian Renaissance painting.

In a groundbreaking 2014 exhibition at the Frist Art Museum in Nashville, Sanctity Pictured: The Art of the Dominican and Franciscan Orders in the Renaissance Italy, curator Trinita Kennedy argued that friars wanted fleshier figures in devotional art so worshippers could vividly picture scenes from the life of Christ in their mind’s eye during prayer and meditation. Friars, particularly Franciscans, read texts such as the Meditations on the Life of Christ from the early 14th century, motivating them to unlock spiritual power by envisioning every little cinematic detail while meditating. It was an innovative concretization in the museum of recent research on these friars from Joanna Cannon, Donal Cooper, and others.

Holly Flora took the argument a step further in her important book Cimabue and the Franciscans (2018). Championed as the first Italian painter to reject Byzantine formulae and paint in a fleshier manner, Cimabue is widely admired as the godfather of Renaissance painting. Flora’s study contextualizes how many of Cimabue’s innovations, which would appeal to later art historians as consequential stylistic breakthroughs, were actually artistic gestures toward the Franciscan friars’ evolving theological interests and contemplative exercises.

What does Cimabue have to do with Siena? Quite a lot, actually. A New Look at Cimabue, opening January 22 at the Louvre, proposes that the artist’s liberty with flesh inspired the Sienese artist Duccio to make his own fleshier bodies in his Maestà altarpiece. And Duccio would go on to prove to other artists in Siena the marketability and appeal of rendering bodies with more dimensionality. It’s wonderful to see panels from the Maestà altarpiece on view at The Met. However, when the didactics withhold how the contemplative practices by the mendicant friars granted artists more leeway with naturalism in both Florence and Siena, viewers only have part of the story.

Studying the influence of patrons is a well-established methodology in art history. The Met missed an opportunity to foreground the influence of the Dominicans and Franciscans as commissioners who were changing the norms of 14th-century art. For instance, wall texts could have explored the wishes and perspectives of friars as patrons. The friars were not bystanders who received artistic innovations in the devotional art they commissioned, as the passive voice of the wall text for the Maestà altarpiece suggests: “In 1308, Ducio was commissioned to paint the grand altarpiece for Siena’s cathedral.” In fact, scholar Peter Seiler has established that the back of the altarpiece is in conversation with the theology of contemplating scenes from the life of Christ. Duccio pointedly excluded some scenes that were “too Franciscan,” betraying the influence of the Dominican Bishop who commissioned him.

The catalog dutifully performed the bare minimum to acknowledge the friars. On page 33, Joanna Cannon’s essay on Duccio’s Maestà altarpiece briefly touched on the meditative practices of the friars and the popularity of meditative texts like Contemplations on the Life of Christ. But the full iconographic and stylistic ramifications were left unpacked throughout the catalog essays. Attention kept turning back to archival documents.

The friars’ cursory treatment in the catalog and exhibition didactics belies how their pivotal role in early Renaissance painting has grown closer to a new scholarly consensus than a fringe theory. In light of this, the subject’s overall elision is all the more unexpected. This gap in the show’s framing is particularly surprising because Cannon, of the Courtauld Institute, was deeply involved in the exhibition and edited the catalog, but key ideas from her 2014 book, Religious Poverty, Visual Riches: Art in the Dominican Churches in Central Italy in the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries, were left out of the wall texts. Likewise, Donal Cooper of Cambridge University wrote for the catalog, yet central ideas from his 2013 book, The Making of Assisi: The Pope, the Franciscans, and the Painting of the Basilica, did not turn up.

It seems that The Met, in partnership with the National Gallery in London, decided to play it safe. At the risk of sounding provocative, is a consensus about the important role of friars arising from formal analysis as well as iconographic and patronage studies from highly esteemed Renaissance scholars too conjectural to present to the general public?

The silence about friars in Siena: The Rise of Painting, 1300–1350 betrays a battle for the soul of art history. Many of us still believe that art historians may observe artworks closely, formally analyze, read relevant texts from the work’s milieu and timeframe, and then formulate arguments about style, patronage, function, and meaning, culminating in what art historian Michael Baxandall once called the Period Eye. Other art historians dismiss these lines of inquiry as too speculative, seeking to limit the discourse to textual analysis of extant archival documents like inventories, contracts, and wills that directly discuss the artist and artwork in question. When The Met enters this fray, it has an opportunity to join an intellectually rigorous debate. Why not present both types of scholarship? Why not offer the latest theories about the friars’ role in shaping artistic change, as well as insights that can be gleaned from a serious review of extant documents — and let the general public decide what they think? If people outside of academia can’t learn about the latest scholarship in early Renaissance art in a major museum exhibition on Sienese painting, where can they encounter it?

Pietro Lorenzetti’s 1320 silhouetted “Croce Sagomata” crucifix may not have the star power of some other works on view. But, as the legend goes, it was before a crucifix that St. Francis experienced his conversion. St. Francis began to suffer the stigmata in his last years, bleeding from his hands like Christ. The orders that followed in his footsteps pushed artists to create work that might surprise and astound viewers with its own fleshy realism, to jolt them into their own conversions. As the Franciscans popularized the stigmata of their founder, 14th-century Sienese artists like Lorenzetti, who undertook commissions for the Franciscans, began to portray the blood and wounds of Christ with more gore, showing off their virtuosity and one-upping each other, and soon an increasingly bloody realism was the norm.

On Sunday, December 22, 2024, a large group of Franciscan friars visited the exhibition while I was there. It was a pointed reminder that the Sienese work on view was originally for a sophisticated Christian audience, not a mixture of tourists and New Yorkers who might not know the intricacies of Christianity. Sadly, the friars declined to be photographed. Their gray robes were not the typical attire for a Met visitor, and their viewings were frequently interrupted with requests for blessings and curious conversations from museum-goers.

In conversation with Brother Lazarus and Brother Agustin, Franciscan Friars of the Renewal, I had the opportunity to explore Duccio’s small panel from his Maestà altarpiece of the calling of the apostles Peter and Andrew through a modern friar’s eyes. The complex theological notion of hearing and honoring the call of God, cherishing moments in which we discern the will of God for us, and making the decision to heed it and get out of our own way, is — to put it lightly — not part of the PR when Old Masters come up at auction houses, or in line with the limitations of short wall texts in exhibitions. Nevertheless, it is the deeper thread of this story of Jesus calling on these two fishermen to serve him.

This panel was part of an elaborate narrative sequence about the life of Christ on the back of the altarpiece, which recent scholarship has shown was a major interest of Renaissance friars. Did Duccio render a reluctance in Peter’s and Andrew’s faces as a reflection on this theology? It was a unique experience to look at a panel with a modern-day friar, to gain insight into what Renaissance friars might have brought to Sienese art as patrons and viewers.

Barna da Siena’s painting of St. Catherine’s Mystical Marriage contains a scene in which St. Margaret bludgeons the demon Beelzebub with a hammer. It is one of the more humorous vignettes in this show. It can also serve as an allegory for the strife between art history and theology. Although the church commissioned many of these works, contemporary art critics and historians have been hesitant to “get lost” in the theological weeds for fear of coming across as preachy or downright boring. As a result, today’s audiences get an art history in which Christianity is so oversimplified that it’s almost beaten out of the art. And given the Catholic Church’s heinous mishandling of the sexual abuse of children, as well as its retrograde ideas about women, trans individuals, and sexuality, it’s not necessarily a moment to assert the theology.

Is something lost when we go light on the theology? Pietro Lorenzetti’s portrayal of John the Baptist set within his Arezzo altarpiece is ten times juicer when viewers have some knowledge about John the Baptist, who did not care for the easy path. He exiled himself in the desert, subsisting on a balanced macrobiotic diet of wild honey for carbs and locusts for protein and fat, indicting the gluttony of the wealthy. He wore wild animal skins instead of the finery of the day. In Luke’s gospel, John gives a lengthy speech about living justly and foretells fire and wrath upon those who do not act virtuously (Luke 3: 7–10). Lorenzetti’s nuanced portrayal amps up this grisly man with a beard of dreadlocks and plays with the long artistic tradition of depicting a grungy John the Baptist. John’s scowl is all about his harsh warnings regarding how those who are not virtuous will burn in the end.

Perhaps the exhibition’s curators do not share John the Baptist’s passion for confrontation and controversy; the show would be richer and smarter if it spotlit new scholarship on how friars catalyzed 14th-century painting. The blood and flesh of early Sienese painting was a breakthrough moment — one that was sanctioned and encouraged by the friars, many of whom payed for it. While nothing in the carefully edited didactics and catalog is inaccurate, the show’s overall framing and emphasis sticks to the facts derived from archival documents and effectively leaves out an innovative new scholarly consensus reached via other methodologies that are widely (albeit not universally) accepted. Upon such a momentous occasion as the first exhibition in New York dedicated to 14th-century Sienese art — a once-in-a-lifetime experience for many of us — the general public deserves to know the fascinating role of friars as influential patrons and an important target audience for the Sienese style of flesh, blood, and gold.

Siena: the Rise of Painting, 1300–1350 continues at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (1000 Fifth Avenue, Upper East Side, Manhattan) through January 26. The exhibition was curated by Stephan Wolohojian, John Pope-Hennessy Curator in Charge of European Paintings at The Met; Laura Llewellyn, curator of Italian Paintings before 1500 at the National Gallery, London; and Caroline Campbell, Director of the National Gallery of Ireland; in collaboration with Joanna Cannon, Courtauld Institute of Art.