The popular opinion isn’t always the correct one.

In January, the average retired-worker beneficiary brought home a $1,976 check from Social Security. While this average monthly payout might not sound like much, Social Security helped to pull 22.7 million people out of poverty in 2022, including 16.5 million adults aged 65 and over.

Despite the undeniably important role Social Security plays in helping aging Americans make ends meet, the foundation of this leading retirement program has been crumbling for decades. While a confluence of factors is responsible for Social Security’s worsening financial outlook, the finger of blame often gets pointed at Congress.

Image source: Getty Images.

Social Security is contending with a greater than $23 trillion long-term funding shortfall

In January 1940, the Social Security Administration (SSA) mailed its first-ever retired-worker benefit check. Since this point, the Social Security Board of Trustees has released an annual report detailing the financial health of the program. This includes taking a closer look at the income and outlays for Social Security each year, as well as forecasting the future solvency of America’s leading retirement program.

In each of the last 40 reports, the Trustees have warned of a long-term funding obligation shortfall. In other words, the Trustees forecast cumulative income received in the 75 years following the release of a report and determined that, inclusive of cost-of-living adjustments (COLAs), outlays would handily outpace income.

In the 2024 Trustees Report, Social Security’s long-term cash shortfall was estimated at $23.2 trillion through 2098. This was up $800 billion from the projected 75-year funding obligation shortfall listed in the 2023 Trustees Report.

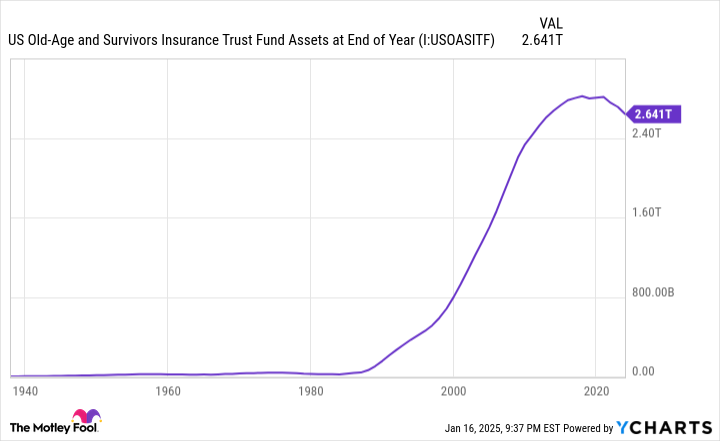

Additionally, the Trustees call for the expected depletion of the Old-Age and Survivors Insurance Trust Fund’s (OASI) asset reserves by 2033. Although the fund responsible for dishing out benefits to retired workers and survivors of deceased workers is in no danger of going bankrupt or becoming insolvent, an exhaustion of the OASI’s asset reserves in eight years would result in an expected reduction in monthly payouts of 21%.

The million-dollar question is: “Who or what’s to blame for Social Security’s deteriorating financial situation?”

The OASI’s asset reserves are forecast to be depleted in 2033. US Old-Age and Survivors Insurance Trust Fund Assets at End of Year data by YCharts.

Did lawmakers in Congress really steal from Social Security’s trust funds?

If you were to peruse social media message boards on topics/articles pertaining to Social Security, you’ll commonly find that Congress is the scapegoat. Specifically, some commentors point to the idea of lawmakers stealing or raiding Social Security’s trust funds to fund wars and other line items, and failing to “put the money back, with interest.”

The thing about popular opinions on Social Security is that what’s popular isn’t always what’s right. In this instance, the idea of Congress stealing trillions from Social Security is completely baseless.

In August 1935, the Social Security Act was signed into law by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Among the laundry list of provisions and rules set forth by the Social Security Act of 1935 is the treatment of any excess income (asset reserves) collected — i.e., income collected above and beyond what’s paid out in benefits and used to cover the SSA’s administrative expenses to operate the program.

By law, any excess income collected by Social Security is to be invested in special-issue, interest-bearing government bonds. U.S. Treasury bonds are exceptionally safe and backed by the full faith of the U.S. government.

What’s most important to note is that every cent of these special-issue government bonds is accounted for. In fact, the SSA publicly updates the combined asset reserve amount for the OASI and Disability Insurance Trust Fund (DI), along with the average interest rate it’s generating on its asset reserves, every month. As of the end of December 2024, the combined OASI and DI held around $2.721 trillion in asset reserves, with an average yield of 2.557%.

The idea that Congress “stole” this money is akin to misunderstanding how a certificate of deposit (CD) at a bank works. If you purchase a $10,000 CD at your local bank that’s yielding 4%, your bank isn’t going to set your cash in a vault and let it collect dust. Rather, it’s going to put that money to work via loans to generate a yield in excess of 4%. Your money hasn’t been stolen by the bank. It’s still fully accounted for, and the bank can make good on your interest payments and principal when the time comes.

Likewise, the federal government isn’t going to let $2.721 trillion in excess cash sit around and lose out to the prevailing rate of inflation. This cash is invested in government bonds (as required by law), which generates much-needed interest for Social Security. If the program was no longer allowed to purchase U.S. Treasuries, it would lose out on one of its three sources of income, leading to sweeping benefit cuts at an accelerated pace.

Image source: Getty Images.

Ongoing demographic shifts are behind Social Security’s financial woes

The answer is clear as day that Congress didn’t steal from Social Security’s trust funds. If you want to know what’s really behind the program’s financial woes, look no further than an assortment of ongoing demographic shifts.

Some of these ongoing changes you’re probably familiar with and have been hearing about for years. For example, the retirement of baby boomers from the labor force is weighing down the worker-to-beneficiary ratio.

Likewise, we’re also living a lot longer now than we were when Social Security retired-worker checks were first mailed in 1940. The program wasn’t designed to dole out benefits to retirees for multiple decades.

But there are other subtler demographic shifts that are/will have a big impact on Social Security. For instance, net legal migration into the U.S. plummeted by 58% from 1998 through 2023. Migrants into the U.S. tend to be younger, which means they’ll spend decades in the labor force contributing via the payroll tax, which is Social Security’s primary funding mechanism. In short, one of the biggest problems is that not enough legal migrants are coming to the U.S.

The U.S. birth rate is also at an all-time low. Although a lower birth rate doesn’t immediately hurt Social Security, the worker-to-beneficiary ratio is going to be pressured even further 10 to 20 years from now when not enough new workers are entering the labor force to cover eligible beneficiaries.

The other issue is rising income inequality. In 2025, all earned income (wages and salary, but not investment income) between $0.01 and $176,100 is subject to the 12.4% payroll tax. Roughly 94% of all workers will earn less than $176,100, and thus pay into Social Security on every dollar they earn.

On the other hand, around 6% of workers earn north of $176,100 and will have any income above this figure exempted from the payroll tax. Over time, a higher percentage of earned income has been “escaping” the payroll tax.

Lawmakers do deserve blame for not putting their heads together sooner to strengthen Social Security. But there’s absolutely no evidence that Congress has stolen from America’s leading retirement program.