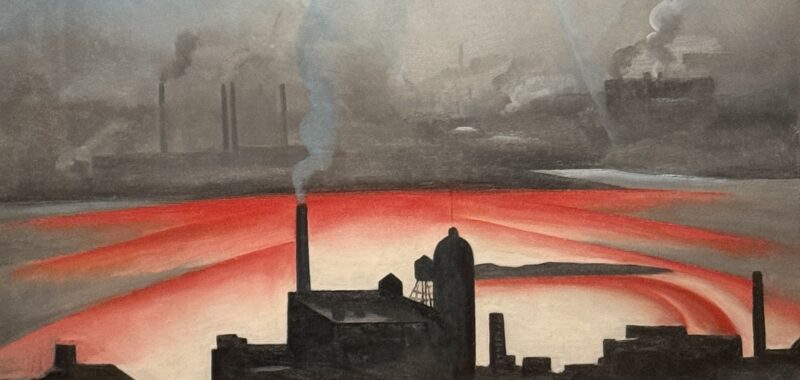

CHICAGO — Before Georgia O’Keeffe painted her legendary Southwestern scenes, she spent years depicting a very different kind of landscape: the harsh and smoky urban canyons of New York City. After she married photographer Alfred Stieglitz in 1924, they moved into an apartment on the 30th floor of the Shelton Hotel. Living in what was then the tallest residential building in the world, their bird’s-eye view inspired a masterful series of experimentations with abstraction, perspective, and scale. “My New Yorks would turn the world over,” she said. But she was discouraged from exhibiting these angular, dark paintings, which the art world’s reigning men viewed as too masculine for a woman artist.

It’s only now, a full century later, that these works are the focus of a dedicated exhibition. Georgia O’Keeffe: “My New Yorks” is on view at the Art Institute of Chicago (AIC) through September 22.

Whether illuminated by the blinding sun during the day or glowing windows and neon signs at night, O’Keeffe’s skyscrapers offer insight into a transformative period of her life, nestled between her first forays into abstraction and her subsequent love affair with the desert. Her famed studies of scale, in which small flowers and shells are blown up to massive proportions, take on new meaning when placed next to her towering, pitch-black skyscrapers — which, the exhibition’s wall text tells us, is the way she originally presented them.

It is particularly surprising that it’s taken so many decades for these paintings to get a proper showing, given how popular they were in their own time. “Her skyscrapers actually sold for a lot of money,” Curator Sarah Kelly Oehler said in an interview with Hyperallergic. “Several of them sold directly out of exhibitions.” It helped, she added, that they were made and shown during “a moment of skyscraper mania.”

But for a woman artist, the fad was a double-edged sword. The hard-edged aesthetic of modern architecture, it was assumed, was solely a man’s domain.

“The men decided they didn’t want me to paint New York,” O’Keeffe later said. “They told me to ‘leave New York to the men.’ I was furious.” Even her own husband discouraged her architectural experiments. “He was obviously instrumental in promoting her career,” Oehler says, “but he certainly had a particular view of what that career should be. There was this expectation that she would bring a certain femininity to her painting that the urban paintings seem to contradict.”

Chicago, the birthplace of the skyscraper and the city where O’Keeffe went to art school, is in many ways a natural home for this show. But the fact that New York institutions appear to continue to overlook these works feels like an extra twist of the knife.

Oehler’s co-curator, Annelise K. Madsen, underlined that these works aren’t completely unknown to the public. Other institutions have requested “The Shelton with Sunspots, N.Y.” (1926), the dreamy piece in AIC’s permanent collection that inspired the current show, for loans. “But it’s typically a one-off,” she said, used in an exhibition to briefly represent the time she spent in New York before moving on to O’Keeffe’s Southwest work. “In some ways,” she added, “they’re hidden in plain sight.”

By the early 1930s, O’Keeffe was exploring using figuration as a way into abstraction, as seen in works like “Manhattan,” (1932) a fever dream of pink architectural zigzags superimposed by soft flowers. “I have always been very free in my approach,” she reflected in one of her many quotes printed on the exhibition’s walls. “I see no reason why abstract and realistic art can’t live side by side. The principles are the same.”

Despite the male-dominated art world’s cold shoulder, O’Keeffe was nothing if not a staunch character. She was adamant about her own genius, and continued to show her New York paintings in galleries such as Stieglitz’s An American Place. “She knew that she was onto something and that she could do something great in the field of modern art,” Oehler says. “And then — she did.”