The following is from Virginie Despentes’ Dear Dickhead. Despentes is a writer and filmmaker. She worked in an independent record store in the early ’90s, was a sex worker, and published her first novel when she was twenty-three. Upon release, it became the first film to be banned in France in twenty-eight years. Despentes is the author of more than fifteen other works, including the Vernon Subutex Trilogy, Apocalypse Baby, Bye Bye Blondie, Pretty Things, and the essay collection King Kong Theory.

OSCAR

Article continues after advertisement

Chronicles of chaos

Bumped into Rebecca Latté in Paris. Memories came flooding back of all the extraordinary characters she played—the dangerous, venomous, vulnerable, poignant, heroic women—how many times I fell in love with her, the countless photos pinned up in countless apartments over countless beds where I lay dreaming. A tragic metaphor for an era swiftly going straight to hell—this sublime woman who initiated so many teenage boys into the fascinations of feminine seduction at its peak, now a wrinkled toad. Not just old. But fat, scruffy, with repulsive skin with that foul-mouthed, female persona. A complete turn-off. Someone told me she’s become an inspiration for young feminists. The fleabag sorority strikes again. Am I surprised? Fuck no! I curl up on the sofa in the recovery position and listen to Biggie’s “Hypnotize” on repeat.

REBECCA

Dear Dickhead,

I read your post on Insta. You’re like a pigeon shitting on my shoulder as you flap past. It’s shitty and unpleasant. Waah, waah, waah, I’m a pissy little pantywaist, no one loves me so I whimper like a Chihuahua in the hope someone will notice me. Congratulations: you’ve got your fifteen minutes of fame! You want proof? I’m writing to you. I’m sure you’ve got kids. Guys like you always reproduce, they worry about carrying on the line. One thing I’ve noticed, the dumber and more incompetent men are, the more they feel a duty to carry on the line. So I hope your kids die under the wheels of a truck, you have to watch them die without being able to do anything, their eyes pop out of their sockets, and the howls of pain haunt you every night. There: that’s what I wish for you. And leave Biggie in peace, for fuck’s sake.

OSCAR

Wow—seriously harsh. Okay, I asked for it. My only excuse is I never thought you’d read it. Or maybe, deep down, I hoped you would, but never really believed it. I’m sorry. I’ve deleted the post and the comments.

Still—that was pretty harsh. At first I was shocked.

Later, I have to admit, it made me laugh out loud.

Let me explain. I was sitting a couple of tables from you on a café terrace on the rue de Bretagne—I didn’t have the nerve to talk to you, but I stared. I think maybe I was embarrassed that my face didn’t even ring a bell with you, and also by my own shyness. Otherwise, I’d never have written those things about you.

What I wanted to say to you that day—I don’t know whether this will mean anything to you—is that I’m Corinne’s little brother, the two of you were friends back in the eighties. Jayack is a pseudonym. My actual surname is Jocard. We lived in an apartment overlooking the place Maurice Barrès. You, I remember, lived in a housing project called Cali, your apartment block was called the Danube. Back then, you used to come over all the time. I was the kid brother, so I spied on you from a distance, you rarely talked to me. But I remember you standing in front of my toy race track, and all you cared about was showing me how to cause a pileup.

You had a green bike, a racer, a boy’s bike. You used to rob sackloads of LPs from the Hall du Livre, and one day you gave me David Bowie’s Station to Station because you had two copies. Thanks to you, I was listening to Bowie when I was nine. I still have that record.

Since then, I’ve become a novelist. Though I haven’t achieved anything like your level of fame, things have gone pretty well for me, and I’ve had your email address for ages. I got hold of it because I wanted to write a theatrical monologue for you. I never had the courage to get in touch.

Best wishes.

REBECCA

Dude, screw your apologies, screw your monologue, screw everything: there’s nothing about you that interests me. If it makes you feel any better, I’m even angrier at the dumb fuck who sent me the link to your post, like I need to be up to speed with all the insults being hurled at me. I don’t give a fuck about your mediocre life. I don’t give a fuck about your collected literary works. I don’t give a fuck about anything related to you, except your sister.

Of course I remember Corinne. I hadn’t thought about her for years, but the minute I saw her name it all came back to me, as if I’d opened a drawer. We used to play cards on a sled she used as a coffee table in her bedroom. We’d open the shutters and smoke cigarettes I stole from my mother. Your family had a microwave long before anyone else, and we used it to melt cheese and spread it on crackers. I remember going to visit her in the Vosges mountains—she was working as an instructor at some chalet where they had horses. The first time I ever went into a bar was with her, we played pinball and tried to look cool, like we’d been doing it all our lives. Corinne had a motorbike—though, given how old we were back then, it must have been a souped-up moped. She smoked Dunhill reds and drank beer with a slice of lemon. Sometimes she’d talk about East Germany and Thatcher’s politics—things no one around me gave a shit about back then.

I hated Nancy, I rarely think about the city, and I don’t feel remotely nostalgic about my childhood—I was surprised to find I had any pleasant memories of those times.

Tell your sister I googled her name but couldn’t find anything, I’m guessing she’s married and she’s changed her name. Give her my love. As for you: drop dead.

OSCAR

Corinne has never had any social media accounts. Not that she’s a technophobe, she’s a sociopath. I remember when you used to come over. Then, later, you became a movie star and I couldn’t get my head around the idea that the girl who used to sit in our kitchen had her fifteen minutes of fame at the Oscars. Back then, fame wasn’t something within the grasp of most people, it was for the select few. It seemed insane to me that it could touch someone who came from our neighborhood. I don’t know if I’d even have dared look for a publisher for my first novel if I hadn’t known you. You were living proof that everyone in my family was wrong: I had the right to dream. I feel like a complete dick that I wrote something vile about you. You’re completely right: it was a particularly pathetic way of trying to get your attention.

You didn’t go to the same school as my sister, so I don’t know how you two got to be friends. When you were in elementary school, your favorite thing was to build housing projects for dolls out of huge cardboard boxes. It was a massive undertaking, and even my mother, who never had much imagination, let you get on with it and never complained about the mess you were making in Corinne’s bedroom. One Wednesday, you brought a fridge packing crate over, and you filled it with shoeboxes to make apartments. The ceilings were too low for Barbies, so you raided the collection of folk dolls my mother had on the shelves of the living room. I thought she’d go ballistic when she saw her precious dolls from Brittany, Seville, Alsace, and wherever living in your development. The moment is burned into my memory, because my mother couldn’t even pretend to blow her top. A sense of joy overrode her sense of propriety. She kept saying, “You’re pushing it,” but before she gave the order to put the dolls back in their clear plastic display cases and tidy the bedroom, she crouched down in front of the installation, shaking her head and saying, “I can’t believe it.” She was only grumbling for form’s sake, and it was obvious. We rarely managed to make Maman laugh, us kids. You managed to cut through her bad moods. Years later, whenever she saw you on the little television set in the corner, she’d say the same thing: “Remember the time she and our Coco took all my dolls down off the shelf and put them in her big cardboard housing project . . . She always had a way about her, that girl. And she was so pretty, even back then.”

I wasn’t even old enough to play Go Fish at the time, but I knew you were beautiful, but I only truly realized how stunning you were one year at the end of summer, a few days before school started, when you walked into our place and said, “Shall we have a coffee?” From that day on, there was no more playing with dolls. Suddenly, you were a grown-up. And I hardly recognized you.

REBECCA

Listen, honey, I’m guessing you know you’re not the first guy to tell me I’m beautiful, or to point out that I’m famous . . .

But I have to admit, you’re the first slimy bastard who’s had the nerve to insult me and, practically in the same breath, follow up with “We come from the same neighborhood, we’ve got shared memories.”

At this point, your sheer dumbfuckery commands a certain respect. But it doesn’t change the basics: I don’t give a shit about you. All my love to your sister, she was a wonderful friend.

__________________________________

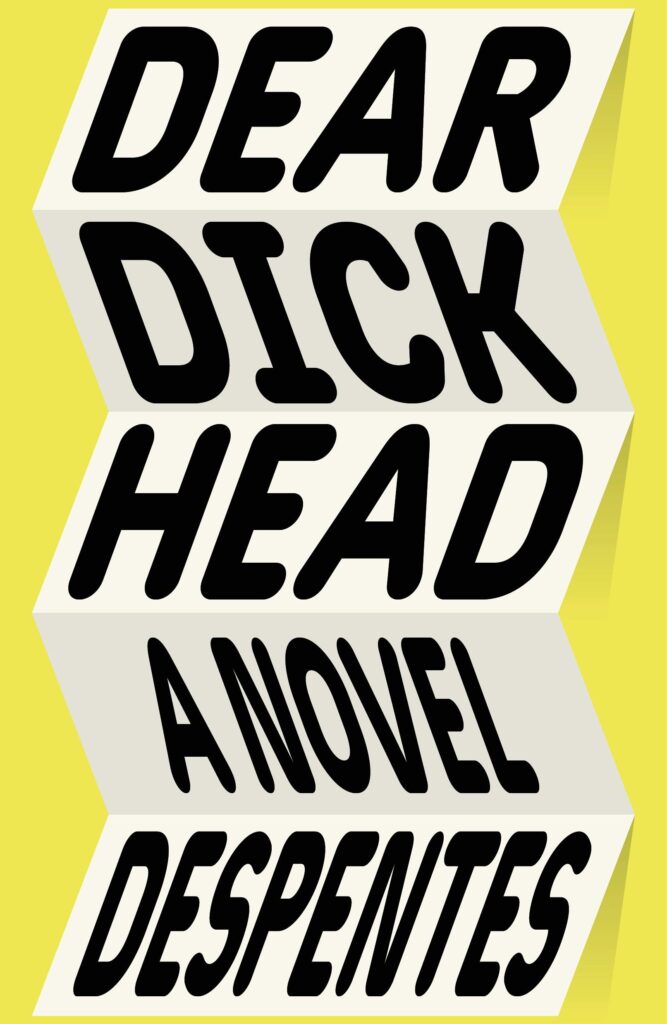

From Dear Dickhead by Virginie Despentes. Published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux, September 10, 2024. Copyright © 2024 by Virginie Despentes. All rights reserved.