Years ago, for reasons I still don’t fully understand, I found myself writing about flight. It started as just a few paragraphs, a bit of spontaneous fiction jotted down in a notebook: a man stood on the roof of a barn, wearing a pair of enormous wings built from wood and cloth. His friend on the ground—the narrator—looked on nervously, ready to call an ambulance. And then the man jumped. Somehow, he flew.

I still remember the surprise I felt as the scene spilled down the page. The thrill of liftoff, a human body lofted in midair. The whole thing only lasted a minute before the man swooned back to earth in a shuddering crash. He was safe, he’d done it. Hoarse, joyful shouts echoed around the field.

That scene became the seed of my novel, The Sky Was Ours, which has a similar pair of handmade wings at its center. It’s about a small cast of modern-day characters obsessed with finding a way to freely navigate the air the way birds do. Success is far from certain, but they’re convinced their efforts have revolutionary potential: the hope is that flight will jam capitalism’s relentless machinery the way nothing else can, allowing the earth to heal and a new, nomadic way of life to flourish. When I put my notebook away on that first day, though, I had no idea that I was embarking on a major project—or that the history of flight would become an obsession of my own.

Maybe the thirst for flight itself became a kind of madness, the kind of desire that makes risk beside the point.

It happened slowly. I kept returning to the scene I’d written, fascinated by something in its basic formula—man, barn, wings. The impossible pull of the sky. In time, I started to flesh things out, developing my first tentative sense of who these people were, and why they were attempting something so audacious.

Before long, I ran into a more practical question: Was a book about self-powered flight science fiction or magical realism? Was it literally, physically possible to fly like that, or could such a thing happen only in the realm of fantasy? This wasn’t a topic like time-travel or mind-reading, after all. Flight—as birds and bugs, drones and planes show us every day—really is possible, even unexceptional. But are we capable of it, physically? Did anyone really know?

I started to look into the biology and physics of self-powered flight, which led me to start researching the history of aviation before the Wright Brothers. That’s when a whole secret world started to emerge—riveting, wildly dangerous, and largely forgotten.

It seems the urge to fly has always been in us, though that desire grips some more powerfully than others. Surviving historical records describe attempts at birdlike flight going back at least 1,000 years. The 9th-century Andalusian polymath Abbas Ibn Firnas supposedly experimented with a feather-covered winged glider that carried him some distance (he injured his back badly in the landing). In the first years of the 11th century, the medieval Turkic philologist Abu Nasr al-Jawhari jumped from the roof of a mosque in some kind of winged mechanical contrivance, falling straight to his death.

Around the same time in Britain, a Benedictine monk named Eilmer attached handmade wings to his arms and legs and launched himself from the tower of Malmesbury Abbey. According to his monastic successor, the influential 12th-century historian William of Malmesbury, Eilmer was inspired by the myth of Daedalus and Icarus, which he believed to be literally true. His experiment was surprisingly successful, though it had brutal consequences: He soared over 600 feet before smashing back into the earth, shattering both legs on impact. (“He used to relate as the cause of his failure his forgetting to provide himself a tail,” William wrote.) Eilmer may have been the first person to travel any meaningful distance through the sky, but he remained on the ground for the rest of his life.

Injuries like that, in those days, could have life-altering consequences, even if you managed to survive. And yet people kept trying—the historical record describes subsequent, bone-snapping dives off a tower parapet in Perugia, from the walls of Scotland’s Stirling Castle. Locals in Troyes, France still speak of Denis Bolori, an Italian watchmaker who jumped from the top of Saint Pierre cathedral in a pair of spring-loaded wings, reportedly flying nearly a mile before crashing to his death in a nearby field. These high leaps were feats of unimaginable daring. And yet the early aeronauts must have talked themselves into believing, on some level, that they had a shot at success. Until you convinced yourself of that, how could you possibly jump?

Or maybe the thirst for flight itself became a kind of madness, the kind of desire that makes risk beside the point. But not everyone was so reckless. Around 1500, Leonardo da Vinci famously started to sketch plans for a flying machine in his notebooks—but it’s assumed he had the good sense to leave his designs in the drafts folder.

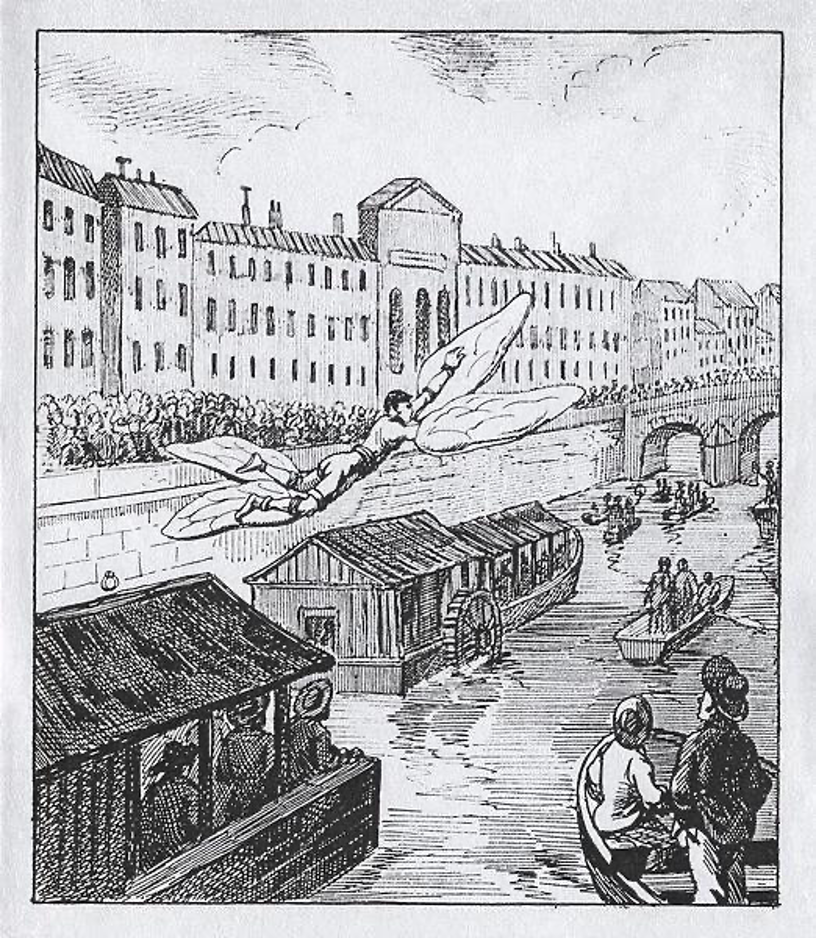

In the 1680s, the Italian Renaissance physiologist Borelli determined that human musculature wasn’t sufficient to achieve bird-like flight; according to the historian Lynn Townsend White, this conclusion helped to divert focus onto developing lighter-than-air gas balloons instead. Yet some still tried. In 1742, Jean-François Boyvin de Bonnetot, a Parisian marquis, announced his intent to fly across the Seine. A crowd assembled to watch him leap from the roof of a nearby building with wings strapped to all four of his limbs. Apparently, he struggled against the air for a moment before plunging down toward the river, landing on the deck of a washerwoman’s barge—breaking his leg in the fall.

The marquis’s stunt had a significant literary outcome, if not a scientific one: It inspired a young writer named Jean-Jacques Rousseau, one of the onlookers that day, to publish a piece called “The New Daedalus” about the practicality of human flight. Years before he became one of the most influential Enlightenment philosophers, Rousseau was asking questions about how—or when—we might break the chains of gravity. “Is it entirely true that the impossibility of ascending into the air is demonstrated?” he wrote. “We walk upon the earth, we sail upon the sea, we even swim in it and skim through it. Why would the path of the air be prohibited to our industry? Is not the air an element like the others? And what privilege can the birds have to exclude us from their abode?”

A few decades later the Montgolfier Brothers managed the first manned ascent in a hot-air balloon, a development that coincided with the rise of steam power—the rapid advance of these technologies coincided with a renewed interest in attaining birdlike flight. This was especially true in America, where newspapers routinely carried stories about would-be inventors claiming their patented devices could deliver astounding aerial feats. “A man in New Orleans has invented a flying machine, which he says he will have completed by Christmas,” an indicative 1826 blurb in Rhode Island’s Warren and Bristol Gazette reported. “He proposes to carry the mail, and can take one or two passengers—no danger at all.”

American papers from the period are strewn with reports like these, filled with outsized claims and delusions of grandeur. A mathematician from Philadelphia who claimed his apparatus was ready for sale begged Congress to give him a monopoly over commercial production. An inmate at the Virginia Lunatic Asylum, “crazy on the topic of a flying machine,” worked peacefully on his gizmo all day along—but when a fellow resident questioned his engineering prowess, he was murdered in a fit of pique. Some had loftier goals. In 1860, an abolitionist named Thaddeus Hyatt offered $1,000 to anyone who could create a successful flying machine. His goal, in part: to help enslaved people escape the South in an Underground Railroad of the air.

As time went on, stories like these were met with widespread skepticism, and were often played for laughs. A mid-century piece in the Detroit Free Press described the exploits of a certain Mr. Fulger, who announced a plan to fly to Grand Rapids. “Exactly what took place cannot be described, as everyone was laughing so that his eyes refused to see,” the reporter covering the event wrote. “There was a jump, a flop, two or three keel-overs, a rustling of silk, and the audience saw Mr. Fulger lying on his stomach on the ground, the spreading wings making him a figure comic beyond description…He claimed that he lost his balance at the critical moment, or else would have sailed away like a Muscovy duck, but declined to repeat the experiment again.”

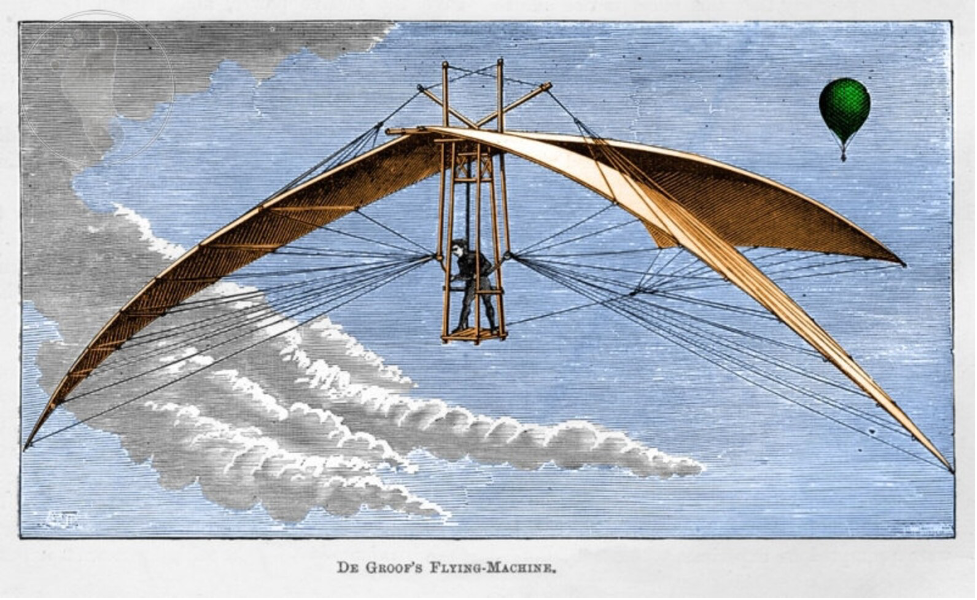

The mocking tone was understandable, given that disasters frequently occurred on both sides of the Atlantic. In 1874, a Belgian shoemaker named Vincent DeGroof created a flapping device and traveled with it to London, where he convinced a balloonist named Joseph Simmons to tow him up 1,000 feet in the air to test it. In a widely misreported incident, local media gave Degroof credit for a successful flight—headlines screamed about a “flying man.” First-hand witnesses told a different story: the balloon had come down again, they said, with the terrified passenger still attached.

A second attempt a week later quickly went off the rails. The wind picked up, and the balloon lost control. DeGroof spoke no English, and Simmons spoke no French, so the two yelled at each other in broken German as they careened toward the tower of St. Luke’s church. This time, Simmons let DeGroof go. As the machine fell, it collapsed like an umbrella with its doomed inventor still inside. He was killed on the spot when he hit. Simmons narrowly avoided his own fate after his balloon came down a few miles east in the path of an oncoming train.

In his 1894 treatise Progress in Flying Machines, the French-born aviation pioneer Octave Chanute took stock of dozens of flight experiments. It’s a wildly entertaining book, one that wryly describes the (often fatal) exploits of deluded souls like DeGroof alongside more serious efforts. Despite the many failures, real science was advancing.

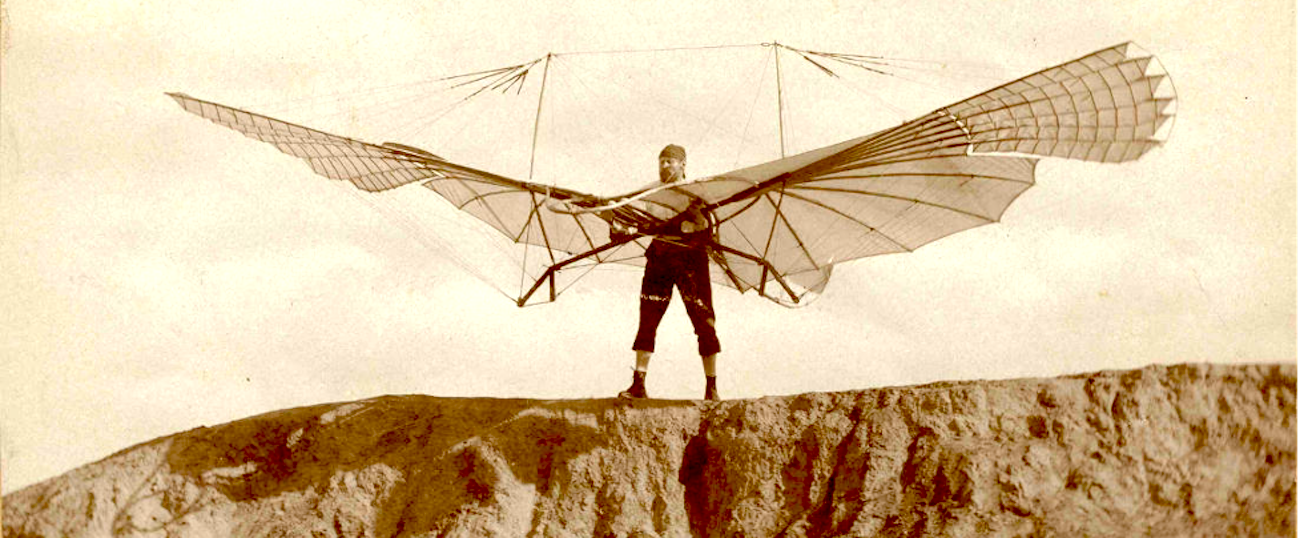

A skilled, innovative engineer in his own right—he’d later go on to assist the Wright Brothers at Kitty Hawk—Chanute reserved his most exuberant praise for Otto Lilienthal, a brilliant and athletic German who designed and built gliders modeled on bird anatomy. Strapped to his apparatus, the winged Normalsegelapparat, Lilienthal successfully soared from great heights countless times in glides of thousands of feet.

Lilienthal had been obsessed with flying since his boyhood, crouching in the meadows of Anklam to track storks’ paths through the sky. He really believed that it was humanity’s destiny to one day fly freely through the air, and dedicated his life to demystifying the mechanics of bird flight, and adapting what he learned into his own sets of wings. A passionate and dedicated scientist, Lilienthal was first to put a rigorous scientific language around the physics of air travel. His “fixed” gliders couldn’t actually gain elevation without a windy updraft, though they could travel considerable distances when launched from high places.

I wonder, too, if flight can be a proxy for another kind of longing.

Lilienthal became an international celebrity, and papers reported breathlessly on his experiments. “At last, a flying machine that really flies,” one 1896 headline ran, above an etching of Lilienthal aloft above a transfixed crowd. But he wasn’t content with glides alone. He wanted to fly, and had learned enough to believe it was possible—though he felt the scientific community’s reluctance to conduct practical experiments was holding progress back. He likened the challenge ahead to inventing a bicycle from a scratch: You could only get so far thinking abstractly. Eventually, you had to get on the thing and try to ride.

By 1896, he was working on a new model of the glider with movable wings designed to allow the wearer to ascend freely, the breakthrough he’d spent his whole life dreaming about. It would be the culmination of decades of methodical work, putting into practice everything he knew. It wasn’t to be.

On August 9, 1896, Lilienthal was testing his glider—the standard one, in a routine exercise, something successfully done thousands of times—when he stalled out in a sudden updraft, losing momentum while 50 feet in the air. Lilienthal knew how to handle this situation, according to his modern-day biographer, the German aeronautical engineer Marcus Raffel. But he over-corrected, and ended up crashing head-first into the ground. The accident left him paralyzed from the waist down, and he lapsed into a stupor before dying the next day. The last words he uttered, reportedly, reaffirmed his commitment to his art: “Sacrifices must be made.”

Lilienthal’s accident was grieved across the world, a calamity felt across borders. Hundreds of mourners joined his funeral procession in Berlin. It also ended the quest for autonomous flight, and in that sense marks a kind of double death. Because if even he couldn’t ride the wind safely, who else would be crazy enough to try? People close to him took steps to ensure that wouldn’t happen. At the request of his widow Anna and brother Gustav, the wings Lilienthal had crashed in were burned, along with his other, newer designs. Destroying their beloved Otto’s work was a startling decision, and a moving one: as if, in their anguish, they felt it was better to close the door Lilienthal had opened.

Some of those experimental aircraft were already partially complete when they were destroyed, their tantalizing secrets purged with smoke. And so the question I started with—can we really fly?—remains unresolved. But in a sense Lilienthal’s legacy was only just beginning. When a bicycle salesman in Dayton, Ohio named Wilbur Wright saw a headline about the accident in the local paper, the news would change his life, and ultimately ours.

“My own active interest in aeronautical problems dates back to the death of Lilienthal in 1896,” he told an audience in 1901. “The brief notice of his death which appeared in the telegraphic news at that time aroused a passive interest which had existed from my childhood and led me to take down from the shelves of our home library a book on Animal Mechanism…”

Ultimately, the Wrights would take flight out of the realm of animal mechanism, pushing us toward something much more practical and industrial—the airplane. And though the approach they inspired has since come to dominate the skies, the experience Lilienthal and his predecessors wanted has still eluded us except in dreams: to swim through the air on our own strength, the sky like an infinite lake.

A few oddball figures, like the Boston opera singer Madame Helene Alberti—who believed in the 1930s that “the day is not far distant when we will be able to entrust our bodies to the air”—continued to experiment with flight according to Lilienthal’s paradigm. But the moment had passed. Self-powered flight fell away as an ambition, abandoned and then forgotten.

Barry Haliban, the flight-mad inventor at the center of The Sky Was Ours, wants to wake us up to that possibility again. He’s driven wild by knowledge of how close Lilienthal came before the world went in a very different direction. The design of Barry’s wings are heavily influenced by Lilienthal, whose scientific writings about wing engineering and construction helped to inform my descriptions in the book. But in a deeper sense, Lilienthal helped to shape Barry’s psychology: like his predecessor, Barry is haunted by the fact that this beautiful, simple, everyday act could prove so unattainable. To change that is the animating purpose of his life.

What is that desire about, really? It’s tempting to believe the human obsession with flight is ultimately physical, as Barry sometimes suggests—we simply want to move like that, experience the primal thrill of traveling through the air with no ground below. We watch birds do the impossible and marvel at it, filling with a question Judy Garland once sang about: “why, then, oh why can’t I?”

But I wonder, too, if flight can be a proxy for another kind of longing. Our desire to rise up and away from present circumstances, unbound by the things that constrain us. To replace what is with what could be—to make a world that’s more generous and merciful, more beautiful, more just. Is that such a fantasy? To rise up against our most ruinous instincts—against systems that demand our endless toil, against our craven trashing of the planet, against the mad obscenities of war—and refuse them in the name of something else?

A woman walks the subway as I write this, singing as she begs for change. “Love me gently, love me gently,” she sings, a song I’ve never heard but somehow know. She sings and the thing she wants feels very close at hand, within reach of our straining fingertips. I can still imagine a world that grants her wish.

__________________________________

The Sky Was Ours by Joe Fassler is available from Penguin Books, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.