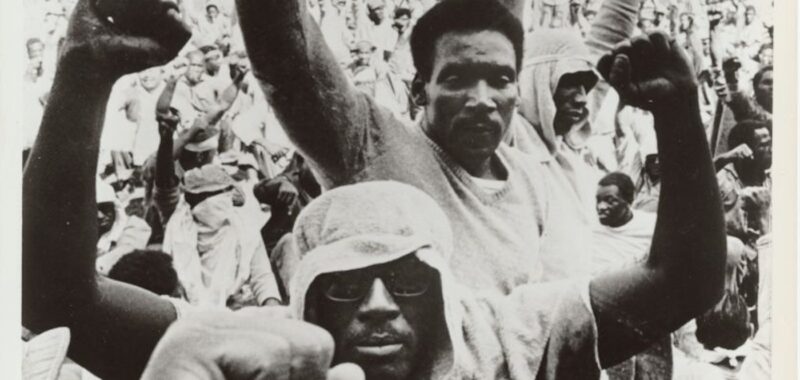

You don’t have to be one of the nearly two million Americans currently incarcerated to have an idea of what prison looks like, whether accurate or not. Audiences have long feasted on sensationalized narratives and pop cultural dramatizations, from escape fantasies like Cool Hand Luke (1967) to the acclaimed dramedy series Orange Is the New Black. But with The Warehouse: A Visual Primer on Mass Incarceration, published by PM Press in June, co-authors James Kilgore and artist Vic Liu aim to offer a realistic visualization of contemporary life in prison and the complex history of how the US built the world’s largest system of incarceration. Across nearly 200 pages, they layer archival photographs of historic uprisings, graphic charts highlighting demographics and the disproportionate population of Black and Latino people in prison, collages of fear-mongering “War on Drugs” headlines, and illustrations of everyday details described by incarcerated people firsthand.

Now a writer and activist, Kilgore himself spent six and a half years in the California prison system in the 2000s after living as a fugitive in South Africa because of his involvement with a far-left organization. He is clear on his abolitionist stance and frames it in well-researched terms. “The US government spends about $80 billion per year on prisons and jails,” Kilgore writes. “This $80 billion could: build 1,000 high schools; construct 320,000 low-income apartments; pay the salaries of a million nurses; cover the operating costs of 1.6 million wind turbines.”

There’s an overwhelm of facts and figures in The Warehouse, all of them bleak. Black kids are six times more likely to be detained than White kids are; one in six trans people has been incarcerated; the average prison cell is six by nine feet. But the accompanying hand-painted illustrations by Liu — who chose to only use materials available to create art in prison — clarify the numbers, countering the tendency to reduce people to stereotypes or mere statistics. “I firmly believe that text is elitist,” the artist recently told Them magazine. “Twenty percent of Americans are illiterate. We exclude so many people when we exclusively encase information in text.” Liu paints objects that don’t make it into Hollywood’s depiction of jail time, like melted red M&Ms used as ad-hoc lipstick or a tube sock over a telephone receiver, a practice that, according to the Marshall Project’s reporting, was recommended for germ protection at a Washington prison.

The book’s most evocative images, though, arguably result from a collaboration between people on the “outside” and those on the “inside.” Since 2009, the grassroots project Photo Requests From Solitary invites those held in long-term solitary confinement to request a photograph of anything at all, and then finds a volunteer to take it. Kilgore and Liu’s inclusion of these images acknowledges the need for incarcerated people’s agency in their own narratives. From photos of a frog on a rock to a pink sunset over water, these images are as much a part of the visual story of imprisonment as are the infographics and sketches of quotidian life.