My mother and Uncle Claude finally stepped out of the office. My uncle put back on his hat and smiled. “Now we’re headed for Rome.”

Article continues after advertisement

Little did I know that the worst hour of my life was about to start.

It happened quite suddenly with Uncle Claude’s attempt to leave Naples and head north onto the Autostrada del Sole, the relatively new highway connecting Naples to Rome. The problem, however, was how to find the entrance to the autostrada.

At first my uncle stopped the car and, addressing a traffic conductor, stuck his head out of the window and with his high-pitched voice shouted, “Scusi, vigile,” and proceeded to ask directions to the highway. The tall, elegant vigile, dressed in white with a white tapered helmet, pivoted with the agile grace of a ballerina, politely lowered his head to the driver’s window, and briefly explained the way to my uncle, who thanked him and drove on. But on reaching an uphill crossroads, he felt lost again and determined to ask another traffic cop, “Scusi, vigile…,” but once again, not finding the directions in any way fathomable, banged both palms on the steering wheel and began shouting, first at the car, then at Naples, which he called a befouled hole filled with urchins and criminals, and then let out his fury on the three of us. I was a complete imbecile, he said, with a fourth-grade knowledge of Italian, my brother a simpering toad who might as well be deaf like his mother, and finally my mother, who should have tried a bit harder to help him with directions but naturally couldn’t understand a word because her illiterate parents had put her in the care of witch doctors who made sure to keep her a deaf-and-dumb mutant condemned to deaf-dumbness for the rest of her deplorable, meaningless life.

My mother had no idea what he was saying but could tell from his ruddy complexion and protruding mandible that he was beyond furious. At the next crossroad, “Scusi, vigile…”: high-pitched voice, affected deference, and seething incomprehension. By then my brother and I were almost ready to guffaw when, hearing my brother whispering something to me, he turned around and, raising his voice again with a stare filled with undiluted venom, said, “As for the two of you, eat your puny candies and shut your little mouths.” Any excuse for humor instantly ebbed from the back seat. But to this day those two words, Scusi, vigile, have remained a source of humor and horror between us.

The trouble with abuse when it is dealt so implacably is that it leaves a mark, and you end up believing it.

At some point one of the vigili had suggested taking a sinistra, a left turn, but my uncle was turning right. So, thinking I was being helpful, I reminded him that the traffic conductor had said left, not right. What ensued was a battery of insults. “Keep that tongue of yours in your silly mouth and don’t dare open it again in my car. You’re unable to understand anything, least of all the instructions of a vigile.” Then, under his breath, “Failures and imbeciles, the three of them, the mother, the son, and that holy idiot”—me.

Never in my life, before or after, had I known such abuse. The trouble with abuse when it is dealt so implacably is that it leaves a mark, and you end up believing it. And for a long time I did believe everything he’d said to me that day. If I struggled not to let myself be swayed by his bullying, I always had the feeling that he had seen through me and assayed every shortcoming, every failure, real, imagined, or yet to come, and from these there was no hiding.

I was a prattler, I didn’t know my left from my right, I was an imbecile and, above all, a failure, something I’d been fearing since writing my first poem at the age of ten. I’d written about an escaped slave who knows he doesn’t stand a chance and, sooner or later, will be caught, because the Roman family who owned him was bound to track his whereabouts. Facing the Mediterranean, he doesn’t know whether to run left or right; he stares at the beach and is thinking of his wife and children and is tempted to turn himself in, but something holds him back. He is hungry, he needs to eat, and though he knows he is doomed, he cannot turn back. They’ll find him and, for the sheer fun of it, put him to death. So he keeps fleeing, never knowing what awaits him.

This was my welcome to Italy.

*

Eventually we did emerge from the city and started driving on the highway. “These idiot vigili don’t know their own city! They need a man born elsewhere to teach them their own streets, their history and their own language too.” As he drove, my uncle decided to test my logic and math and gave me a puzzle to solve, which, I vaguely recall, went something like this: if a car drives at eighty kilometers per hour and bypasses another running at forty kilometers per hour, how much faster will the slower car have to accelerate if it wants to reach destination X at the same time as the faster car?

I couldn’t understand the question, let alone figure out an answer. I said I knew the formula but didn’t recall it just then. “You don’t need a formula, you simply don’t know. Why not say I don’t know, Uncle Claude.” Then, pricked by some evil insect, he asked my brother to decline any Latin noun he pleased. My brother told him he didn’t know Latin but had just started studying it on his own. “So you know nothing, my good man. He doesn’t know math, you don’t know Latin, and clearly neither of you knows Italian, since you couldn’t understand what the vigile was saying.”

I was almost tempted to tell him that he couldn’t understand the vigili either, but stayed quiet. Still, he wasn’t giving up, and turning to my brother, he asked: “What’s the plural of house in English?” “Houses?” the rise in my brother’s voice almost asked rather than answered, no longer certain of being right. “No, it’s pronounced houzez.” “What about the plural of this?” he asked me, pointing to his forehead. “Foreheads?” Like my brother, I hesitated. “Almost right, except you don’t pronounce the h. So English isn’t really one of your strengths either. Now tell me this,” he said, turning to me again, “what book have you read recently?” I told him that I was reading The Greeks by H. D. F. Kitto. “E chi è ’shto Kitto?” Who might this Kitto be? A kitten? he asked in mock-Roman dialect. “An author of detective novels?” And before hearing my explanation, he began poking fun at the name with all kinds of rhymes in Italian, howling with intensified laughter each time he came up with yet another rhyme: “Vitto fritto, zitto zitto, fritto misto, letto sfitto.” My mother, seeing him laughing, and not realizing that her sons were being systematically demolished with derision and scorn, affected a muted smile to harmonize with his beaming joy, which made him think that she agreed with him, and he threw a look of winking complicity at her. “Even your mother thinks you’re a fool, even your mother!”

At some point on the highway he decided we needed to stop at a snack bar. My uncle parked the car and, staring at my mother, brought the bunched fingers of his left hand in front of his mouth to signal the word food. As he locked the car and we began heading toward the restaurant, he put a tentative arm around my shoulder, and I would have accepted and been pleased with the conciliatory let there be no bad blood between us gesture had he not shoved me through the revolving door with a renewed surge of contempt, meaning, Don’t just stand there like a child, be a man and move in. Haven’t you ever seen a revolving door before? Quietly I entered the restaurant. I did not look back, but I was sure that the thought had crossed his mind to slap me on the nape.

From that moment on I swore I would one day come to spit on his grave.

Claude ordered a dish with his favorite wine, Rosatello il Ruffino. My mother ordered a ham sandwich. We ordered spaghetti with tomato sauce because we couldn’t tell what the other sauces on the menu were. And for a quick dessert, my brother and I ordered a strawberry ice cream. Claude ordered a bowl of raspberries. He encouraged my mother to order the same. Knowing he was a miser and that another bowl of raspberries would cause an added expense, she declined the offer. I knew that my mother adored raspberries. But I also knew what was running through her mind. She was still hungry. Watching my mother fold her cloth napkin and put it away, I felt for her. He told me to tell my mother that when eating ham, one should always remove the fat, which is something he’d always done. I took my time passing along his message. “Tell her!” he said. I told her. But she was quick to sense the enmity in the air and simply nodded and whispered that I should tell him to go hang himself. She, too, by then, had determined to spit on his grave.

Several years later, he died in his sleep in a glamorous hotel in Monte Carlo.

I never made it to his grave.

*

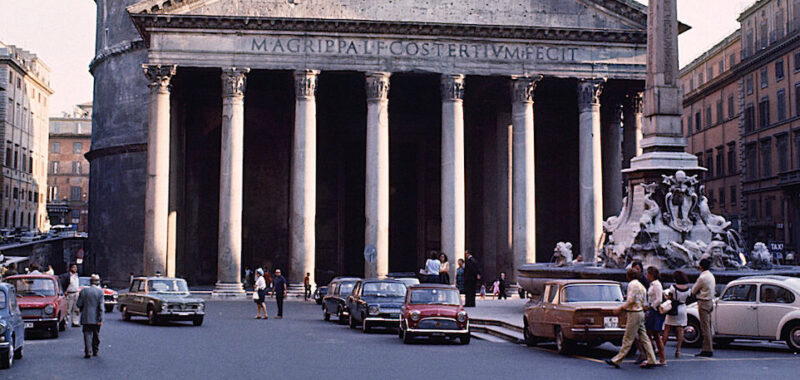

It was late in the day when we arrived at Via Clelia. The neighborhood, it took me no time to realize, was thoroughly working-class—many buses crowding the main thoroughfare of Via Appia Nuova, drab, ill-lit stores everywhere, and so much soot on buildings that time had discolored them. The grandeur of imperial Rome had no place here. Via Clelia itself was ugly, dirty, and at the approach of dusk seemed sad. This, I thought, was a neighborhood for poor folk, not a refugee camp, but not much better. I said nothing, my mother said nothing, my brother sat totally stunned in the car. When we parked and opened the door, we saw a group of screaming boys playing calcio on the sidewalk.

Uncle Claude walked upstairs with us, while my brother and I lugged our two suitcases. He opened the door to the furnished apartment he was subletting to us, and a whiff of something between incense and old wood shavings hit me, as though the place hadn’t been aired in weeks. The apartment was very warm. Uncle Claude opened one window, and all I heard was the sound of the same boys playing downstairs. He then gave my mother the keys, saying that we should make copies at the ferramenta, the hardware store, down the street. He said he hadn’t had time to ask Grazia, the portinaia, our concierge, to purchase some staples for us, but if we hurried we still had time to go to the supermarket on Via Appia Nuova two blocks down. We’d find everything there. Grazia was under instructions to bring up pots and pans and a tiny refrigerator, all of which for some reason she’d been keeping in her basement. One of her brothers had promised to carry it up as soon as he was back from work that evening. “These people are so lazy,” Uncle Claude said. He told us he would come by in three to four days; he was a member of a golf club on Via Appia Antica nearby and had many obligations there. “They made me an important member of the club because I am Jewish. We are in a completely different world here. And you want to go to America!!!”

You feel nothing because there’s nothing to feel, the pain is still working itself out, has yet to come, will come, just never when you expect.

Another put-down.

He said he would send a telegram to my father that very evening to tell him of our safe arrival.

As he was about to go, he remembered to give my mother some bills for buying food. On leaving Egypt, we’d been allowed only the equivalent of five dollars and had spent what we had for extra food in the snack shop on board. Once again, he reminded us to hurry, as the supermarket might be closed; otherwise we’d have to buy what we could at the corner grocery or see what the caffè-bar nearby had for snacks. He explained that every month he would give us a certain sum drawn from my father’s small account in Switzerland, which was under his care. “Not a gold mine by any means, let’s be clear,” he added. Then, before shutting the door, he took a good look at us and said something totally startling: “And please, don’t hate me. I’m no ogre.”

I smiled politely, as if to say, What could possibly have put such a notion in your head? But he didn’t pay me any heed. He nodded three times as though he’d been granted a pardon. Atonement, in his view, however perfunctory, always expiated the crime.

Once he was out the door, my mother, who had a gift for mimicry, imitated his features when he’d tried to charm the girl at the refugee camp. It made the two of us burst out laughing. My brother imitated her imitation, which made me laugh even harder. But we were crushed.

This was our first late afternoon in Rome, and not only had my uncle’s attitude already made me hate Rome, but the thought of living in this small apartment stirred a wave of gloom that none of us was able to tame. We sat facing one another in what appeared to be a living room and didn’t say a word. I don’t know how long this lasted, but when I looked outside again, the streetlights on Via Clelia were already glowing. So this was evening, I thought. I felt the evening’s full weight and couldn’t shake it off. I wished it hadn’t come so soon. I wasn’t ready for evening yet. Maybe it was much later than I thought. Maybe we needed time before facing our first night in Rome. Eventually, Mother found a light switch, and the light helped, but the oppressive, mournful feeling wasn’t lifting away and was heavier the darker it grew outside. When we stood up and walked over to the narrow kitchen whose back window already faced the night, concealing everything that lay beyond, we realized we didn’t even want to know, much less see, what darkness hid from view outside.

What I felt at that moment was not sorrow, not even anger at my uncle. What I felt was the persistent, undefinable numbness that eventually overtakes you and won’t let go. You feel nothing because there’s nothing to feel, the pain is still working itself out, has yet to come, will come, just never when you expect. I tried to feel grief instead; grief was easier because it was factual and thinkable—grief for what was lost, for who we’d been and had left behind, grief for old habits that were meant to die but hadn’t yet, grief for my father, who was still in Egypt and might be arrested on who knows what trumped-up charges before even being allowed to rejoin us, grief for my deaf mother, who knew not a word of Italian and was as broken and rudderless as my brother and I. I felt like a child who had strayed from his mother’s grip and was now stranded and helpless in a huge department store that was about to close for the day, except that I knew Italian and my mother did not, and I was the grown-up and she the child.

That night we did go to the supermarket. We’d never been in a supermarket before, nor pushed a shopping cart, nor could we tell one coin from the next. We liked the supermarket. The only ones we’d seen were in American films. But none of us was hungry. All we wanted was to sleep and put the day away. The apartment had three rooms and a tiny alcove, but that night the three of us slept in the same bed.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Roman Year by André Aciman. Published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux, a division of Macmillan, Inc. Copyright © 2024 by André Aciman. All rights reserved.