On November 23, 2018, the Special Investigation Team submitted a charge sheet accusing eighteen men of conspiring together to murder activist and journalist Gauri Lankesh. By then they’d arrested sixteen of those men. The two remaining men were still at large. The charge sheet was a whopping 9,235 pages in length, a record of all the evidence the SIT had assembled against the men to make the argument that they should be charged with murder: forensic reports, hand-writing samples, witness statements, statements from most of the accused, narrative summaries, and much, much more, most of it in Kannada.

Article continues after advertisement

Johnson at The Indian Express gave me a scan of the thing when I got back to Bangalore in the summer of 2019, but I needed time to get the relevant parts translated into English. I was especially impatient to read the statements of the accused, in Kannada and Hindi, which alone totaled 255 pages.

There was one long English-language document included in the charge sheet: an entire book, titled Kshatradharma Sadhana, multiple copies of which were found in the suspects’ possession. Its author is Jayant Athavale, the founder and guru of Sanatan Sanstha. Eighty-six pages long, the book is volume 1E in Athavale’s Science of Spirituality series; its subtitle is Spiritual Practice of Protecting Seekers and Destroying Evildoers.

“Violence towards evildoers is non-violence itself,” he assures the reader. “It is a sin not to slay an evildoer….The sin of killing the undeserving is the same as not slaying one who deserves it.” And for these killings, the law of karma “does not apply”: “Destroy evildoers if you have been advised by saints or Gurus to do so. Then these acts are not registered in your name….But this is also not registered in the name of the saint or Guru because They both are the manifest forms of God.”

The spiritually motivated assassin is sure to succeed. “It does not matter if one is not used to shooting. When he shoots along with chanting the Lord’s name the bullet certainly strikes the target due to the inherent power in the Lord’s name.”

The book is nothing less than a manual for murder in the cause of spirituality.

The book is nothing less than a manual for murder in the cause of spirituality. It makes a point of repeatedly clarifying that this is not a metaphor: it is an extended argument for the “physical destruction” of any people whom “seekers” determine to be “evildoers,” complete with many quotations from multiple scriptures, all of them framed in a way that seems to exhort the reader to kill. The book enables murder as an act of goodness.

“Society has been invaded by germs in the form of evildoers. If these germs are not destroyed then the entire society shall be destroyed,” Athavale writes. “In order to protect yourselves it is now imperative to destroy evildoers in society otherwise they will destroy you.”

In typical Sanatan Sanstha style, everything is broken down mock-empirically, complete with multiple tables. “In general, society comprises of five percent evildoers and ten percent seekers. The rest of the eighty-five percent are passive, self-centered good-for-nothings from the social point of view as they are concerned only about their families.” The “crusade against evil,” Athavale calculates, is sixty-five percent a spiritual battle, thirty percent a psychological battle, and five percent a physical battle.

When a seeker is ready to destroy evildoers, the first thing to do is “start making lists of evildoers.” He suggests consulting the pages of Sanatan Sanstha’s newspaper, Sanatan Prabhat, for inspiration in compiling a hit list, because it publishes “news about evildoings.”

When the time comes to kill, the seeker should show no mercy. “Evildoers do not deserve to be pardoned. One should certainly not be moved by the emotional talk of an enemy and should never let him go scot free or pardon him.”

“This subject is quite different from others,” Athavale admits in the book’s conclusion. “Consequently you will probably be stunned. However you should contemplate on the topic then you will realize how essential it is for you with regard to spiritual progress.”

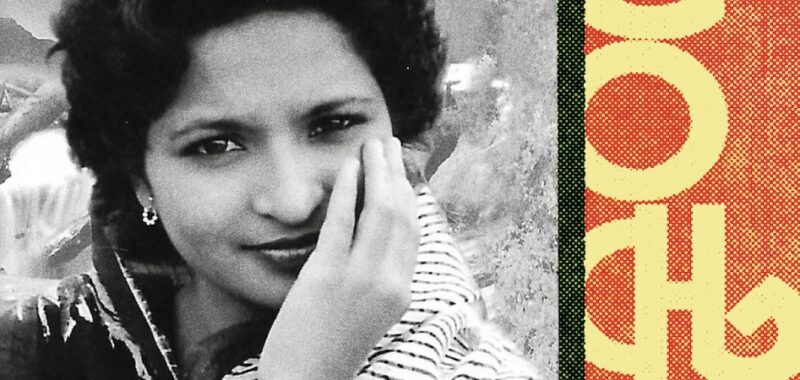

Before anything else I caught up with Gauri’s sister Kavitha. We met in her office on the top floor of her father’s office building, a room lined with posters of her own and her father’s films, along with favorites by other directors: Kiarostami’s Close-Up, Tarkovsky’s Nostalghia, Kurosawa’s Ikiru, along with Roman Holiday (Lankesh was an Audrey Hepburn fan). She looked stylish in a dark blue kurta and tortoise-shell glasses, and as usual she cried silently and continuously whenever we spoke of Gauri, wiping her tears away with a pink handkerchief.

Since I’d last seen her, she’d released a new film called Summer Holidays—a light, charming adventure about a group of kids who stumble on a mystery and learn a lesson about conservation. It was a family affair: in her film debut, Kavitha’s daughter, Esha, played the lead, alongside one of Indrajit’s sons. Even one of the family dogs had a role. And Gauri appeared in a cameo, which Kavitha filmed two months before her death—as a crusading journalist, naturally.

She was still deciding what to make next. “I got a very bad offer for a film that I didn’t like, so I refused to make it,” she said.

Some coming-of-age comedy, four boys trying to lose their virginity. You know how it is. I’m not in that mental state of mind. I mean, if I was twenty, maybe I would have thought of it. I’ve got another idea with two women protagonists. And one more. I seriously want to work on Gauri’s film, actually. A film on Gauri.

The next day we met at her home in southern Bangalore. Kavitha mentioned that her neighborhood, because it’s well-off, is a BJP stronghold, and she constantly hears her neighbors sing the praises of Modi. Her neighbor across the street stopped talking to her after Gauri was murdered. Esha appeared to say hello, a tenth grader now, bright and polite and seemingly happy.

I’d told Kavitha I’d wanted to interview Esha, but in the event I couldn’t bring myself to do it. It didn’t feel right to interrupt a fourteen-year-old’s good mood with a journalistic interrogation about her aunt’s murder. Anyway, I knew how she felt because she’d published an essay about it a few months before.

“One of the feelings I have thought about the most is pain,” Esha wrote.

A year has passed but I feel the pain as if it was yesterday. Maybe I am not crying anymore like I was back then, but the void inside me still feels just as deep as it did that day. Initially, I felt very angry towards the killers. I wanted to hurt them the way they hurt her. I wanted them to experience the pain we felt. I still do. But the bitter truth is that my aunt will not come back even if they suffer.

Gauri had always had a special connection with children; “in her spontaneity, she was like a child,” her friend Mamta Sagar wrote. She kept a stash of little toys to give to friends’ kids when they visited. If someone brought a kid to one of her parties, she’d sit on the floor and devote her attention to them. “She was very genuinely interested,” Vivek Shanbhag told me. “And they loved her, because she was very gentle with them.”

Esha was born just seven months before Gauri Lankesh Patrike debuted, and she was the only thing that could pull Gauri away from her newspaper and her activism. When she was little, Esha wrote, Gauri would tell her bedtime stories of Cinderella—but Gauri’s Cinderella was always a career woman who would never pine for a prince and who had adventures on her own terms.

When Esha was older, Gauri would take her to hear speeches by student activists or make her watch them on YouTube. But she didn’t want children of her own. In a 2015 interview, Pratibha Nandakumar made Gauri laugh by asking her how her life would be different if she were married.

“They’d have left me by now!” Gauri said, listing her weekly, her publishing work, her activism, and her court cases. “This leaves no room for me to miss anything. I am not one of those ‘traditional Indian women.’” At some point she had an abortion; I’d heard from one friend that she’d been pushed into it and regretted it, but Kavitha told me this wasn’t so.

“I knew what she did, I knew what she loved and I knew especially what she hated, but I did not know how many lives she had influenced,” Esha wrote. She was astonished to see how many thousands showed up to view her body. “I wish I had spent more time with her,” she wrote. “I wish I had told her more often how truly I loved her. I wish I had told her how proud I was of her and the work she did.”

A few days later I finally got to meet with M. N. Anucheth, the lead investigator of the SIT. Now that his investigation was nearly complete—”ninety-five percent done,” he said—he was able to talk and generous with his time.

We met at the Bangalore police’s Criminal Investigation Department complex, which is where the SIT is headquartered, and as we passed through its generic white cubicles, he told me that now there were fifteen members of the SIT, but at its peak there were no fewer than 226 police officers working on the investigation into Gauri’s murder, and forty or fifty people whose contribution was significant.

“It is not just a one-person show,” he said. “It was not Mr. B. K. Singh or it was not Anucheth who cracked the case. It was this SIT. So we always refer to ourselves as the team, never individually. That was a decision we took from the beginning: we swim together or sink together.” (Later in our conversation, though, he did single out Singh for praise: “I think he’s a genius! Very soft-spoken. His mind is always working. Even when he’s sleeping, I think he’s always thinking about this case.”)

Handsome, fit, and very serious, Anucheth walks fast and talks fast, although sometimes he’d freeze while searching for a word, apparently out of total exhaustion. (A few months earlier, citing his success in the Gauri investigation, the Supreme Court handed him an additional assignment as the new lead investigator for the Kalburgi assassination, on top of his primary duty as a deputy commissioner of police.) He wore a khaki uniform, a navy-blue beret, and a tidy black mustache, and laughed only when I asked him an unexpected question, but otherwise never smiled, and often winced.

From the police perspective, “it was a blind murder case,” he said.

The motive itself was not clear. We were groping in the dark. That was the biggest challenge. So we probed along the Naxal line, personal enmity, something to do with her official dealings, something to do with her writings, her personal life. A lot of people had filed defamation cases against her. There was a rumor that some Naxalites were unhappy with her, but we were able to talk with them and we sent feelers out, and that angle was ruled out. We probed even Indrajit Lankesh, because there was a fight with Gauri, and there was some bad blood, but it had been sorted out. We were not able to get clear direction. But we started eliminating the chaff from the grain.

He quoted a famous Sherlock Holmes line: “When you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth.” (In my experience, Indian Police Service officers love to quote Sherlock Holmes.) “We started closing in. There were only a few angles remaining. Finally we narrowed it down to this right-wing thing.”

The reason the charge sheet needed to be so unusually long, Anucheth explained, is that there were no direct eyewitnesses to the murder—and under Indian law “ocular evidence” is paramount.

The clincher for focusing on the right-wing angle, he said, came around two months into the investigation, when ballistic testing definitively proved that the same gun had been used to kill three of the victims in the pattern: Gauri, Kalburgi, and Pansare. Pansare had been shot with two guns, and the SIT was furthermore confident that the second gun used to shoot Pansare was also used on Dabholkar, the first victim in the pattern— meaning that only two guns were used for all four murders.

One of the suspects told the SIT that he’d thrown the guns into Vasai Creek, near Mumbai. The Central Bureau of Investigation was now attempting to search the creek for the weapons. It sounded like an enormous headache, not least because the search was constrained by environmental regulations since the creek is a protected mangrove area.

Before filing their 9,235-page charge sheet, the SIT had invoked Karnataka’s organized-crime law—a move that suggested that Gauri’s murder had been committed on behalf of a larger organization or syndicate. The invocation of the organized-crime law also had the benefit of extending the deadline to submit the document by another ninety days.

The reason the charge sheet needed to be so unusually long, Anucheth explained, is that there were no direct eyewitnesses to the murder—and under Indian law “ocular evidence” is paramount. That, he said, was their second-biggest challenge. So they had to collect an enormous amount of circumstantial evidence to compensate for the shortcoming.

Among the sixteen men so far arrested, he said, “some have been very reluctant to cooperate with the investigation. Some have cooperated with the investigation. I would say that the person who shot her did cooperate with the investigation.” He said that they had custody of Parashuram Waghmare, the suspected shooter, for fifteen days, and he cried the entire time.

In contrast, Amol Kale, the man they suspect of being the group’s ringleader, “just doesn’t care. He’s remorseless, just so coldhearted.” But when Kale realized how much they’d already figured out, “he was shocked. We were able to tell him that whether you cooperate or not, we’re going to find out. The shock on his face—that was good.

“This gang had done everything possible to conceal themselves,” he said. “It was very carefully and meticulously planned. They conspired, they planned, they rehearsed, they practiced, they executed. All five stages were done very professionally. The amount of evidence we get is very less. So we had to use some scientific techniques.”

Their first breakthrough after the ballistic match was aided by machine-learning analysis of phone data. First they compiled a list of phone numbers associated with thousands of different extremists, both on the left and on the right, and focused on calls placed in the two or three months leading up to Gauri’s murder. Based on the patterns they detected, they put a small number of people on the list under surveillance and intercepted their phone calls.

“One of them happened to be K. T. Naveen Kumar,” he said. “He was not known to us before this. We were not initially sure of it.” But then, in late October 2017, they listened in on a phone call in which Naveen Kumar told a friend that he’d been in hiding because of Gauri’s murder. “At random, why would a person talk about Gauri’s case?” he asked. “And why would he be absconding? We continued our surveillance. Then we realized they were planning the murder of Professor Bhagawan.”

They also collected all of the Bangalore traffic police’s CCTV footage from a five-kilometer radius around Gauri’s house and used artificial intelligence to pick out all motorcycles carrying two helmet-wearing people. This process helped them determine exactly one thing: the make and model of the motorcycle. Based on its local prevalence, this reduced the number of possible motorcycles from around five million to around thirty thousand.

They used AI, too, to help generate images of some of the suspects still at large. The accused deliberately knew very little about each other, precisely to make it difficult for the police if any of them got caught. “So we’ll get probably a fake number, fake name, fake accent,” he said. “The only thing we’ll get real about him is his physical description.” These images helped them make their second arrest, Sujith Kumar, whom they knew little about aside from what Naveen Kumar told them.

Local tech companies aided the SIT with these A. I. and machine-learning techniques, he said. “They don’t want to be named. But there are two companies which helped us.” I said that he must have had a lot of help to choose from, given that Bangalore tech firms are where lots of AI innovation is happening. “It’s…happening, but not many people want to cooperate once they realize it’s a criminal investigation,” he said. “They don’t want to get involved. It was difficult to find a company which does it and is willing. We did find. They did help us out. And we are very grateful for that.”

In the CCTV footage recovered from Gauri’s house, the shooter appears for only six seconds, and his face is obscured by his motorcycle helmet. And because it was night, the camera was shooting on infrared mode, which further muddied the image. “We had to prove very rudimentary things, like, is this the same guy, was he at the spot?” Anucheth said. “So we did something called gait analysis.”

In June 2018, after the SIT captured Parashuram Waghmare, they brought him to Gauri’s house and had him reenact the shooting to see if he moved in the same manner as the figure in the footage. “We reconstructed the entire sequence of events and recorded it using the same CCTV camera, and then it was matched frame by frame.”

Another suspect took the police to a wooded area where Waghmare and the other conspirators had practiced shooting. The SIT came equipped with an EDAX machine (for energy dispersive X-ray analysis). “We looked for holes in the trees, and we’d use this machine to see if there’s any copper or iron in it. That means a bullet has passed through, and we’d just cut it down and find it.” One of those bullets was a ballistic match for the ones that struck Gauri.

Given how little many of the suspects knew about each other, the interrogations were a challenge. “They kept the information compartmentalized,” Anucheth said. “It was on a need-to-know basis. There was only so much he could tell you. So it is like doing a big jigsaw puzzle where you have only few pieces of the puzzle.” Sometimes it was literally a puzzle—the police had to decode hundreds of phone numbers written in a cipher and dozens of aliases and code names that they found in the diaries they recovered from five of the suspects.

Mostly, though, the contents of the diaries were genuinely diaristic. “Generally their feelings, their perceptions in life, daily thoughts,” he said.

There is a rule in Sanatan Sanstha that you have to write your own faults. A lot of the diaries had this kind of faultfinding. So one guy writes that he had a dream about a girl and he had those nasty thoughts. They write down their faults, and they discuss it, and he tries to overcome it. That’s one of the techniques in their cult. It did give us an insight into their psychology.

The killers, it turns out, were writers, too. Unfortunately for me, their diaries are not included in the charge sheet.

Finally, there was genetic evidence. At one of the group’s hideouts, the SIT found a few strands of hair. DNA testing matched them to Amol Kale, the suspected ringleader.

DNA was also essential when the SIT recovered four toothbrushes. One of the suspects had been tasked with destroying all the killers’ clothing and other personal effects. He was supposed to have burned everything, but the things he couldn’t destroy by burning he threw on the roadside on the outskirts of Bangalore; every hundred yards or so he’d throw more evidence out of his car window.

When the SIT captured him, he showed them the spots where he’d tossed the items. They found a bag with four toothbrushes in it, and one of the toothbrushes was a DNA match for Waghmare, the shooter.

Anucheth seemed entirely unbothered by the constant criticism the SIT received when it appeared to the public that they had made no progress in the first half year after Gauri’s murder. “Naturally, we were derided, teased, criticized, mocked,” he said. “There was a lot of sarcasm spewed on us. But that never affected us, because when you’re doing a professional job, you can’t put a time limit on it.”

I asked him about the suspects’ allegations that they’d been tortured in custody. He groaned audibly. “Yeah, see, this is a standard tactic adopted by this set of advocates for this organization wherein they make allegations against everyone,” he said. “Right from the beginning they started making allegations against the police, citing custodial torture, assault, ill treatment.” He categorically denied that the SIT had tortured or otherwise mistreated the suspects.

I noted that the charge sheet includes the entirety of the Sanatan Sanstha book Kshatradharma Sadhana and asked him if the SIT had concluded that the killers were taking orders from the group. “There’s a link which is missing,” he said. He said that they know that the group was inspired by the writings of Sanatan Sanstha, and at least four of the accused had been members of the group, but the SIT found that they quit the Sanatan Sanstha “specifically to go underground” and start their nameless assassination syndicate.

“Specifically whether the orders came from Sanatan Sanstha, we have not been able to prove conclusively.” He said that they came quite close; in the course of their investigation, they found that the top editor of Sanatan Sanstha’s daily newspaper—Shashikant Rane, alias Kaka—was very close to the assassins.

But Rane died of a heart attack in April 2018, before the SIT knew of his involvement and before they’d arrested anyone but Naveen Kumar. He seemed to think that the moment to directly implicate Sanatan Sanstha had passed. Two of the suspects named in the charge sheet were still at large, but he did not expect any additional people to be charge sheeted.

I asked him about the reports that a local TV news channel had ruined the SIT’s plan to arrest one suspect at a wedding. Anucheth laughed with surprise, then looked miserable. “Yeah, it happened,” he said. “It’s all water under the bridge.”

In the end they did capture the suspect, albeit several months later. “The setback was that someone on our team had leaked operational information,” he said. “I was more worried about that, because it would put the operation in jeopardy and my team on the ground in physical danger.”

The officer responsible was removed from the SIT. After that, the SIT members shared their findings with each other only on a need-to-know basis. It occurred to me that this precaution paralleled the way the killers compartmentalized information.

Maybe the only way to function in India as an honest cop, as Anucheth seemed to be, was to lie to yourself.

I asked him if he had any concerns that any member of the SIT might be politically sympathetic to right-wing extremism. This struck me as highly probable, given that hundreds of policemen were assigned to the SIT at its peak. “Well, I think we were lucky to have a very professional investigation team which put aside its personal ideology or personal beliefs and just concentrated on doing the job at hand,” he said.

I don’t for a single instant believe any of our people were compromised or put their personal beliefs or ideologies ahead of their own professional work. I think we were lucky. This team was handpicked. So that helped. I myself, I’m a practicing Hindu. And that doesn’t mean that I have to compromise on my work. I mean, see, I don’t care who’s sitting next to me in a train, man. Or when I go to a hotel, I don’t ask, has it been used by somebody? I will not use that plate. When I’m traveling in a flight, I don’t mind chatting up the next person. I don’t ask him what is his religion or what is his caste. Majority of us are like that.

I asked him if, in the Indian police in general, there are political sympathies in one direction or another that interfere with police work. “I don’t think so,” he said.

I’ve been in the service for ten years. Never have I found any political party or anybody telling us to work in one particular way or favor one particular—never. See, end of the day, any person sitting in a responsible position understands the gravity of the situation. You cannot have a situation where people are killed for their voice or their beliefs. I think freedom of speech and expression is a fundamental right, and I think we should do everything in our power to uphold it. And everybody does so. There are some fundamental things which everybody believes in like the right to life, the right to speech. Everybody should uphold it, and they do uphold it. I’m talking about people in power. Otherwise it’s not possible to have a democracy. Democracy is on some fundamental principles. I think there’s a lot of focus in one section of the media to highlight intolerance, or so-called atrocities against the minorities. But I don’t think it is true. I think it is a perception created by certain sections of the media. No government supports any of these activities. When they come to the responsible post, everybody behaves responsibly.

It was one of the naivest things I’ve ever heard anyone say, and it was impossible that such an intelligent and perceptive man could be that naive. We were inundated with evidence of irresponsibility and intolerance among those in authority. It’s well documented that Hindu nationalists work systematically to increase their numbers in India’s police forces, and that Hindutva militias have often worked closely with police during riots and pogroms.

But Anucheth said it with total conviction, and he made a point of saying it. Maybe the only way to function in India as an honest cop, as Anucheth seemed to be, was to lie to yourself.

______________________________

I Am on the Hit List by Rollo Romig is available via Penguin Books.