“The Hunger Artist” (2024) was the first of Joshua Hagler’s paintings that I saw in his debut New York solo exhibition, Nihil III/Already Paradise, at Nicodim Gallery. Impressive in scale, abraded by an open-ended process of layering and scraping, the largely tan, orange, and purple painting depicts a tiger standing on its hind legs, scratching the wall of its enclosure. I learned later from Hagler’s Instagram account that he had previously installed the painting on the distressed walls of the abandoned Cedarvale School in New Mexico.

When I discovered that many of the works in this exhibition had been installed in abandoned churches and schools in New Mexico, where the artist and his wife live with their young daughter, I thought about context and audience, large paintings in abandoned spaces and what happens to them when they are installed instead in a large, pristine gallery, where art and commerce meet.

Hagler clearly contemplated this question after he moved from Los Angeles to the very different geographical environment of New Mexico, where he could afford to work in much larger spaces. In Franz Kafka’s short story “A Hunger Artist,” a nameless performer travels with his manager across Europe seeking a location where he could lock himself in a cage and fast for public spectacle. Unsurprisingly, things devolve when he refuses to comply with his “impresario” and end his fast after 40 days; eventually, he ends up in a circus where he starves to death, shunned by those around him, including audiences. After he dies, the circus reclaims the cage for a panther, who draws huge crowds.

Does Hagler want to be the panther with the large audience in Kafka’s story? What is the alternative to popular entertainers in a world where spectacle and diversion are highly valued? Who does one paint for when success is measured by marketability? Hagler pondered this dilemma after moving away from Los Angeles, where he felt rejected, despite having some exhibitions. What trajectory should he pursue?

This is how he described the inspiration for “The Hunger Artist” on his website:

I had several visualizations, dreams, and in one holotropic breathwork session, a powerful physical sensation of encountering and merging with a mountain lion. In the snowy Sandia Mountains [in New Mexico], I had tracked one a short distance before sanely turning back. When I wanted to draw one, I didn’t try to find it in the wild or turn away from the idea altogether; I went to the Albuquerque zoo where I drew imprisoned cats of all kinds, including lions and tigers.

In recounting his out-of-body experience, Hagler echoes the shamanic belief that the soul is free to leave a given body and become one with another. This threshold experience is essential to the artist’s definition of art, in which his breakdown of the figure/ground relationship through strategies such as merging and layering goes beyond formal issues.

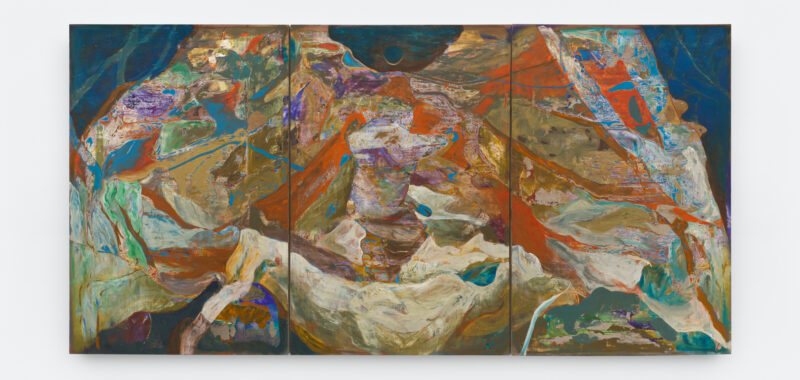

These strategies are evident throughout Hagler’s work, from the contour drawings done in graphite, charcoal, oil pastel, and wax on pages of a found Baptist notebook (dated 1981–2024) to the monumental triptych “The Hermit” (2024), which is 10 feet high and 20 feet wide.

While Hagler worked on the three drawings that serve as studies for “The Hermit” from 1981 to this year, he completed the painting in one year (2024). This indicates that his art underwent a dramatic change — that he shed one self and began growing into another with his relocation to New Mexico. By embracing the state’s landscape, as well as its confluence of cultures and temporalities, from the historical to the geological, he recognized that humans are social animals, but one can choose to align with different societies.

The triptych depicts what looks like a nude man, either leaning against a rock or standing, pointing at the night sky, which is framed by twin buttes. In the middle of the sky floats a lunar eclipse. With their worked surfaces, the different colored, interlocking planes and shapes become a visual puzzle. In the foreground, a ghostly white shape with tints of blue, green, and violet stretches across the triptych, hovering between figural form and geological accretion. I was reminded that when Antonin Artaud entered the land of the Indigenous Tarahumara people in Mexico, he saw a mountainous landscape marked by what he understood as the indecipherable imprints of higher spirits.

This is the path Hagler seems to want to follow, one where logic and convention are left behind in favor of visions and dreams. He has identified this path through his choice of subjects such as a hermit and tiger, and related paintings like “The Gates (Already Paradise)” (2024), whose title indicates that it’s necessary to see the gates, but not to pass through them, to know that transcendence is possible.

In “The Book of Hours (Yeso, New Mexico, 1957)” (2021), the format — a blackish-brown grid of rectangular sheets adhered to a larger dark brown surface — suggests that a calendar might be covered over. Yeso, New Mexico, is a ghost town of a half-dozen houses, founded in 1906, when the railroad was extended to this spot. Its only business is a post office. Having moved into a realm brimming with heightened states of consciousness, I am curious to see where Hagler, one of the most engaging and interestingly ambitious artists to make his New York debut in a long time, goes to next on his path.

Joshua Hagler: Nihil III / Already Paradise continues at Nicodim Gallery (15 Greene Street, Soho, Manhattan) through October 12. The exhibition was organized by the gallery.