VENICE — The air was full of energy outside Jeffrey Gibson’s (Mississippi Choctaw/Cherokee) United States Pavilion at the Venice Biennale on Saturday, October 26, after White People Killed Them finished their performance. Raven Chacon (Diné) played a keyboard synth, pitch shifter, and distortion pedals, as well as vocalized and used a loop cassette player, while John Dieterich played the electric guitar at the base of Gibson’s bright-red sculpture comprising empty plinths and pedestals titled “the space in which to place me,” sharing a name with the exhibition itself. Marshall Trammell played a drumset on top of the interactive sculpture’s front pedestal, performing with such passion that his bass drum kept sliding toward the edge of the pedestal. Near the end of the performance, Gibson rose from his seat in the audience and retied a cement block placed on the base of the drum to prevent it from crashing down. Afterward, several Native curators, artists, and scholars confided that they felt their insides vibrate from the sheer volume of the electronic music.

This was the last performance of if I read you/what I wrote bear/in mind I wrote it, a three-day convening hosted by Bard College’s Center for Indigenous Studies to “address the interdisciplinary, transnational nature of Jeffrey Gibson’s work in the US Pavilion.” Before White People Killed Them took the stage, members of the Colorado Inter-Tribal Dancers and Oklahoma Fancy Dancers welcomed the large crowd gathered around the pavilion and performed to hand drumming and singing by Miwese Greenwood (Otoe-Missouria-Chickasaw-Ponca). At the beginning of the blended performance, dancer Kevin Connywerdy (Kiowa and Comanche) told the audience that Gibson’s presence at the pavilion was not only an honor for the artist himself but for “all of our people.”

As a Diné audience member who spent the previous three days at the convening, I shared Connywerdy’s sentiment of Native pride. It was stunning to witness the various performers making the sculpture their stage, with dancers surrounding it in brightly colored regalia that matched the color of Gibson’s block text across the top of the pavilion that read “THE SPACE IN WHICH TO PLACE ME” and “WE HOLD THESE TRUTHS TO BE SELF EVIDENT.” As Greenwood’s drum echoed, it was not only heard but deeply felt.

This specific feeling of a hand drum’s echo is found across the United States at Native cultural events, powwows, and performances. And in accordance with the spirit of Native humor at those events, Connywerdy jokingly told the audience to get ready to hear some Grateful Dead when he introduced White People Killed Them. In the middle of the performance, Nick Ohitika Najin (Cheyenne River Sioux) from the Colorado Inter-Tribal Dancers seamed the two separate performances. The crowd cheered as he rejoined the sculpture-stage and danced around the trio. The bells on his regalia joined Trammell’s drum beat. While Chacon’s fingers quickly moved around the keyboard synth, Ohitika Najin waved his feather fan around the keyboard. This fusion of radically different styles was representative of the convening, which gathered Native and non-Native poets, academics, artists, musicians, curators, teachers, and students. The convening as a whole felt like an energizing disco, a kaleidoscopic exploration of Native identities in all their rich dualities, contrasts, and dichotomies: familiar and unfamiliar, past and future, joy and sorrow, detailed and monumental.

During the first panel of the convening, Gibson spoke with Bard Center for Indigenous Studies Director Christian Ayne Crouch as well as the pavilion curators: Kathleen Ash-Milby (Navajo), curator of Native American Art at the Portland Art Museum, and independent curator Abigail Winograd. Gibson noted that his first studio visit when he moved to New York in 2002 was with Ash-Milby, who added that, a few years later at the 2007 Venice Biennale, the two discussed one day showing Gibson’s work in the US Pavillion.

“It seemed like this super crazy idea,” said Ash-Milby, adding that she felt frustrated “that there wasn’t more recognition for Native artists” at the time.

Those of us in the audience carefully followed the story of how that idea became reality, and the very reason we all sat together in an auditorium in Venice. Beginning in 2022, that eagerness eventually led Gibson, Ash-Milby, Winograd, commissioner and SITE Santa Fe Executive Director Louis Grachos, and their teams to prepare to apply for the US Pavilion exhibition space, which they received in 2023 and opened this past April. Ash-Milby described the process as a “nonstop sprint.” Gibson, currently an artist-in-residence at Bard College, reflected on this process and said, “I think the fact that the story would be ‘Jeffrey Gibson as the first Indigenous artist with a solo exhibition’ is true, but it was really difficult for us to push the story in a much broader way.”

“I think one of the goals was for people to understand how many different tribal nations there are, how many different cultural contexts there are, and how many different languages there are,” he continued. “My hope is that we’ve been able to push some of those conversations to the next subject or the next place.”

As an attendee, I noticed collaboration woven into all of the events. There was no strict focus on Gibson, but rather an emphasis on his web of relations with colleagues, friends, and inspirations. It reminded me of Gibson’s book, An Indigenous Present (2023), a curated selection of work by over 60 contemporary Native artists, musicians, and writers. For Native people, such spirit of collaboration is a familiar one, forming the key to our relationships and communities.

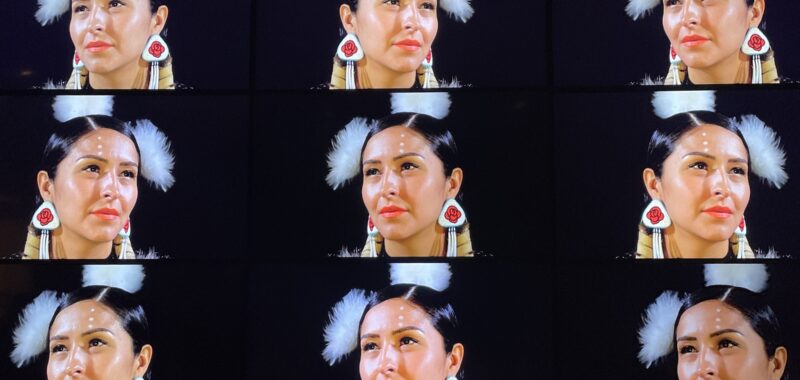

At the pavilion itself, Gibson’s artwork wholly embodies this spirit. In the final room, several screens play his short film “She Never Dances Alone” (2020), comprising a mesmerizing kaleidoscopic abstraction of Sarah Ortegon HighWalking (Eastern Shoshone and Northern Arapaho) dancing in jingle dresses to “Sisters” by the Halluci Nation, a song that fuses electronic and First Nations pow wow music. Gibson brought the club and the pow wow to Venice.

As I watched, I noticed that multiple fellow onlookers tapped their feet and moved their heads to the steady drumbeat as the collaged shots of Ortegon HighWalking dancing overlapped with one another. “She Never Dances Alone” reminded me of the crucial ways in which Indigenous matriarchs are born from and molded by community with other Native women, which we continue to create and cultivate. Ortegon HighWalking is the only person featured in the exhibition; the other figures are tall, ancestral sculpture spirits and intricately beaded busts set on marble bases. Alongside her fellow Colorado Inter-Tribal Dancers, Ortegon HighWalking performed at the opening and closing performances for the convening. She introduced herself to the crowd as a staff member for the Native American Rights Fund, a nonprofit legal advocacy organization for Native people. When I spoke with her afterward, she commended Gibson for his openness and sincerity throughout their collaboration. In keeping with that collaborative ethos, most of the performers and speakers presented in groups and in dialogue with one another.

Notably, Layli Long Soldier (Oglala Lakota) read her poetry on her own. The space in which to place me borrows its name from lines in Long Soldier’s poem “Ȟe Sápa,” published in her acclaimed book, Whereas: Poems (2017). The name of the convening, if I read you/what I wrote bear/in mind I wrote it, is culled from another of Long Soldier’s poems, “Vaporative.” She began her reading at the Human Safety Net building in Piazza San Marco with a dedication to children, reciting a poem she had written the night before. The words were displayed across the screen, and we read along to Long Soldier’s gentle and intentional voice: “I dedicate this to all children / the world’s children and for those children who suffer I pour each vowel humbly as a cup of water.” The words rang through the room. I, and I’m sure many others present, immediately thought about the Palestinian children who were suffering at that very moment in the Gaza Strip.

As Long Soldier continued to read, she shared writings about how she and her family processed the news of a mass grave of 215 Indigenous children found on the grounds of the Kamloops Indian Residential School in Canada in May of 2021. The moving testimony touched on the seething reality of pain within past and present Native life. In the pavilion, a geometric rainbow multimedia work by Gibson referenced the assimilation policies of US federal Indian boarding schools. The work displays the title, which is a direct quote from the Commissioner of Indian Affairs in a 1902 letter, in the artist’s stylistic block text: “THE RETURNED MALE STUDENT FAR TOO FREQUENTLY GOES BACK TO THE RESERVATION AND FALLS INTO THE OLD CUSTOM OF LETTING HIS HAIR GROW LONG” (2024).

The trauma of Native American boarding schools has trickled down to many Native people, and as Long Soldier read, my mind flashed to this work by Gibson. Long Soldier explained that she, her son, and her aunt coped with their pain by braiding 215 pieces of fringe in honor of the students, which eventually became a large artwork resembling a northern-style wing dress. When Long Soldier finished reading, multiple audience members wiped tears from their eyes. She received a standing ovation.

To continue the dialogue, poet Natalie Diaz (Gila River Indian Tribe/Mojave) asked the audience during her panel session the next day to consider the stakes of this gathering of Natives and non-Natives around Gibson’s work. She answered her own question with a powerful declaration: “I believe the stakes are at least each of our bodies. And I also wager that, since the American pavilion is next door to the Israeli pavilion, which did not exist until 1950 after the Nakba, what else is at stake is the bodies and freedoms of Palestinians.”

Though the last official program for Gibson’s time at the US Pavilion, this convening did not feel like an ending but rather a spark igniting the work to come. In a panel about future-making, scholar Jolene Rickard (Tuscarora) offered crucial insights about the direction of Indigenous art. Rickard’s husband, Timothy McKie, presented on her behalf and read her words about Haudenosaunee beadwork, tribal sovereignty, and Native diplomacy. “Why share this history? The arts are essential in the worlding process,” read her speech. “Indigenous peoples globally live in the strike zones of the climate crisis. We all live in the age of end-stage capitalism…Is it possible that Jeffrey Gibson’s takeover of the US Pavilion has challenged us to consider the space in which to place me will be realized in 100 years in an Indigenous future present?” Rickard called in via Zoom for a Q&A, sharing that she believes there will one day be Indigenous pavilions at the Venice Biennale that recognize tribal nationhood and sovereignty.

“Nothing comes easily. Change is hard,” she continued. “My presentation this morning was just a small element of all of the change that our ancestors had to constantly stand up for.”

In the same panel, scholar Philip Deloria (Yankton Dakota Sioux Nation) commented on Gibson’s incorporation of quotes in his work at the pavilion from influential Black leaders and advocates like Frederick Douglass, Booker T. Washington, and Nina Simone. Deloria asserted that the space in which to place me is an “Indigenous voicing of an African-American critique of American claims to authority on the basis of human rights” and that the exhibition invites us to develop an Afro-Native conversation as a way of thinking through history. Throughout the panel, audience members feverishly nodded their heads, hummed in agreement, and scribbled down notes. Despite the anxieties about the future that loom over us all, there was also a strong atmosphere of solidarity in that room. As the panel moderator Ginger Dunnill commented, it was a rare “space of love.”

So, what’s next for the space in which to place me after it closes at the end of this month? What will stitch it to the “Indigenous future present” that Rickard mentioned? One answer to these questions is further education. Irene Kearns and Catherine Hammer from the National Museum of the American Indian told me in an email that the museum is creating educational resources in partnership with the Portland Art Museum and SITE Santa Fe, both of which selected five educators each to attend the convening. Through this endeavor, images and videos of Gibson’s exhibition in Venice as well as art activities will be available to K–12 classrooms across the country.

I asked Margarita Paz-Pedro (Laguna Pueblo/Santa Clara Pueblo), a teacher at the Institute of American Indian Arts and Central New Mexico Community College, to share her biggest takeaway from the space in which to place me and the convening as a whole. “What I see in this work by Jeffrey Gibson is ‘the space in which’ we place ourselves is what we make it and what we want it to be,” she replied. “Gibson has shown us a path of possibilities.” Indeed, the sense of collective strength was as palpable as the beats of the drums, the rhythms we felt in our gut. I hope we can translate that thrumming energy into the classroom, where the next generations can imagine and advocate for an Indigenous future.