In his 1958 work of criticism The Poetics of Space, Gaston Bachelard notes, “It is better to live in a state of impermanence than in a state of finality.” There is perhaps no fictional figure who understands this better than Pinocchio, the titular character of the 1883 tale penned by Italian satirist and children’s author Carlo Collodi. Pinocchio is crafted from a piece of living lumber, a chunk of wood with spirit who needs to be mobile in order to move across the world. He is born in a state of impermanence and, ultimately, he arrives in a state of finality: he becomes a flesh and blood person. This is why I read Pinocchio as a tragedy.

Article continues after advertisement

*

It’s the summer of 2019, and I am at a writing residency in Red Wing, Minnesota, running a path that borders a creek through the woods. If I run fast enough, I can avoid the mosquitos while still hearing the running water. At one point I stop to observe what I count to be seventeen turtles lingering on the top of the water. Passing under a bridge, I see a collection of what I think are hornets nests but later discover are the homes of barn wallows. I am thinking a lot about shells (the turtles) and nests (the barn swallows), both literally and figuratively.

I pass someone biking the opposite direction and I smile and they smile back. This is the universal sign for, “We are engaging with each other, sharing this moment through locked eyes, and we’ll likely never do so again.” It is then—just after I smile at this person and happen to let my gaze slip from their face to a butterfly managing its tentative route to the ground—that I see something flat and blue with text along the path. I could keep running to the rhythm of the creek. Instead, I choose to stop and read it.

I am traversing the universe in order to find the story I need to tell.

In the chapter of The Poetics of Space titled, “Nests,” Bachelard talks about the paradoxical imagery bird nests instill in us. They are contingent and precarious, of course, but they also create the illusion of safety and security. This paradox resides between the seemingly contradictory knowledge—perhaps we could call it the fiction—that requires we be both confident that the homes we build will protect us while also aware that those structures cannot fully defend against whatever antagonism lingers beyond its walls.

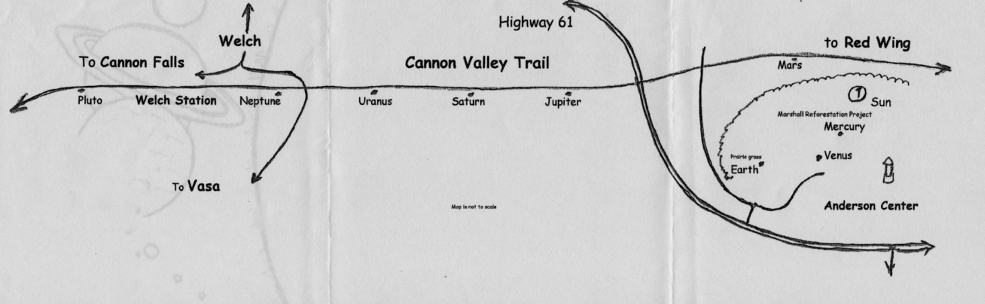

On the rectangular piece of blue cement is a planet with rings. Above this reads one word: Saturn.

I take stock of Saturn and then I finish my run, return to the house that I am calling home for a month. I am in a liminal space—not yet moved from a rental in Charleston, South Carolina to my new life in a rental in Salt Lake City, Utah. I am in the middle of that move and in the middle of the country: Red Wing, Minnesota.

“It is better to live in a state of impermanence than in a state of finality,” Bachelard says. At this point, I believe him.

At dinner that night, the other artists and I discuss what we are working on and then we talk about our mediums: light and dance and language. I tell them I found Saturn. We talk about politics. We talk about food. We talk about how feeling is evoked from certain colors and what we wish we didn’t remember from our childhoods. We eat a lot of ice cream. We walk it off by taking a stroll through the sculpture garden. We go to bed. I re-read Johnathan Swift’s 1726 classic Gulliver’s Travels for about the 100th time. It is a book exposing the absurdity of Swift’s nation but obliquely enough to feel like entertainment instead of political critique. I decide the book I am writing will be about a world without birds and what that might do to the human mind. I decide the book is also a kind of 21st century retelling of Pinocchio. It will be a story about a puppet who wants to be real because the world around her isn’t. Or is, but doesn’t feel so anymore.

Two nights later, a revelation. The minute we all sit down to dinner, the light artist turns to me and says, “I went for a walk today along the path to try to find Saturn. But I didn’t. Instead, I found this.” He then proceeds to show me a photograph, an image of a blue cement block with a planet-like orb and the name Jupiter embossed above it.

My pulse, in this moment, goes wild. Something is unfolding in my heart. There is magic in the world. Buried in the borders of a path in the woods, there is evidence the world contains riddles, which a woman could choose to solve. It has been a long time—a very long time—since I have felt the blood pumping through my form like this, from the welcome disquiet of possibility.

“The world is the nest of mankind,” Bachelard says in the chapter titled, “Nests.” In the chapter titled, “Shells” he says, “One must live to build one’s house, not to build one’s house to live in.”

I decide I will find all the planets—each one. I will search for the planets and in so doing, learn what should be done with this not-yet-written book about the puppet woman in a world that is somehow more unreal than she is. I run the path, read Gulliver’s Travels, run the path again. I search for the planets in the morning and at dusk, spend the rest of my time writing pages and pages of a play that I never intend to be performed. I run and I read and I write a play that is longer than a novel and I try to find all the planets. I think: Which artist planted them? I think: How long did it take to do it? I think: Why paint the planets blue?

I find Uranus. Then Mercury and Venus. With the help of the other artists, Neptune and eventually Pluto, which tells me the project was made before the planet was demoted in 2006.

At a dinner in the last week of my month in Red Wing, Minnesota, the residency director reveals she’s learned of my obsession with finding the planets. I tell her what I’m doing, which is living a fiction that is also a truth. I am traversing the universe in order to find the story I need to tell. I have also written over 300 pages of a play that will never be performed, I tell her. The director puts her chin to her chest and I am worried I’m in trouble. Instead, she hands me a pamphlet that contains a map.

In his extremely short story “On Exactitude in Science,” Borges offers an anecdote that illustrates how any map is always incomplete. It is only in the dimensions of a map that perfectly replicates—to the very proportions—the territory it aims to illustrate that a map could truly be called accurate. But a map under those circumstances would be pointless, of course. For it would—in its adherence to perfect replication—hide the very thing is it meant to elucidate.

The project, the pamphlet explains, is not the work of a vetted and successful sculptor. The project is a collaborative, community effort by a science instructor and his students at the alternative school adjacent to the residency house. It was made in 1999. The map reveals the distance between each planet corresponds to their distance in the sky. I’d known they were in order but had no idea the distance was measured accurately. It’s a piece of art made in the name of science by a group of people thinking about the universe at the end of the last millennium.

There is a moment in Gulliver’s Travels when Gulliver is in Laputa and he meets a series of professors who work in speculative learning. They are testing out experiments in language. One of the experiments is this: no language at all. The end of speaking words, so that we only use a bag of items to communicate. This will be in service of brevity but also in service of health, as everyone knows speech “corrodes the lungs.” The logic is that since words are merely stand-ins for objects, we’ll just use the objects themselves. It’s simple. People will carry massive bags around and pull out an object when it’s needed, converse by using objects in response. It will be a universal language. It will eliminate all hierarchy.

Of course, Gulliver’s Travels is satire. The novel is the Western world we know—the world that is familiar—packaged in a world estranged. It is what Dorrit Cohn in her book The Distinction of Fiction calls “fictional” which she distinguishes from “fictitious.” Fictitious claims point toward lies. Fictional claims points toward truths. Bachelard describes the same phenomenon of estrangement in the chapter titled “Miniature” in the The Poetics of Space. Basically he says this: if you look at an object you’ve seen your whole life through a magnifying glass, the object you know so well becomes a different thing altogether.

When I finally find Earth I stand over the blue block, admiring that the moon is also present on this marker, and I think: where is home?

I leave Minnesota with over 350 pages of a play.

I teach my classes, realize I probably made a mistake taking this job, come to understand I likely don’t understand myself, question what it all means, continue to fail to write the puppet woman novel, run miles and miles and miles every day. Then, one day in March of 2020, everything stops. I don’t need to tell you why. For weeks I look out my window. I think of the puppet woman, pulled by the strings of systems she doesn’t know she is controlled by. The world is revealing itself to be more unrecognizable than was thought possible. There is a problem with which we are grappling.

The problem is global. It is planet-wide. I look out my window—as so many others do—and what I see are birds. Many, many people—including me, for the first time in my life—look at the birds.

In The Distinction of Fiction, Cohn says: “Life tells us that we cannot tell it while we live it or live it while we tell it. Live now, tell later. On existential grounds, this différence may be a source of despair.” For the rest of her chapter, she talks about how fiction combats that despair through the use of what she calls simultaneous narration. Basically, that means 1st person, present tense.

Over the next three years, I write the puppet woman book. It is a struggle, but the guts of the story are there from the day I found Earth in Red Wing, Minnesota. The planets are with me all through that writing, lodged in my mind and my heart. One day I realize they are also lodged in the book. The book gets further and further away from Pinocchio but closer and closer to what it needs to be. The play starts showing up inside the novel. The universe directs this. I had thought I was the marionettist, but I am the puppet woman. At least now I know I am a puppet. I try to grow familiar with the forces that govern my strings.

One morning, I wake from a dream about the planets—I dream about the planets a lot, several blue squares planted on the crust of a green Earth—and over coffee I decide I want to know the person behind this project. I need to know the name of the science teacher and what prompted him to make the universe. Bachelard says, “All small things must evolve slowly, and certainly a long period of leisure, in a quiet room, is needed to miniaturize the world.”

After I get his name from the residency director, I find Tom Wolters’ email in a letter to the editor from Physics Today. It is a really beautiful letter. I love the letter so much that I think there is a chance he might not think I am absurd.

They started with the sundial, Tom Wolters writes to me. Students at Red Wing High School—the other institution where Tom taught—found the correct angle for the gnomon and aligned it the night before they poured the concrete to make sure it matched up with the North Star. Each planet marker was formed from a cast made of lumber and plywood and modeling clay. This was all done by the students, who also sketched the orbs of each planet. The lettering was done by a printer where the font was enlarged and reversed. They poured Quikrete into the molds and then cleared the dried cement of the clay that cast the letters and shapes on the block surfaces.

The reason they chose blue is because that was likely the only can of spray paint they had lying around the shop.

Each planet marker weighed 120 pounds so it was a struggle loading them up and placing them at the exact dimensions that would mirror—in miniature—the real distance each planet lives from the others in space. The sundial was about 8 feet long, which is about 1/6,000,000 of the sun’s diameter. Eventually they had to use a surveyor’s wheel because the distance spanned so far—from the sundial to Pluto, which was still a planet in 1999. They’d track the location, then use a wheelbarrow and a shovel to get there and put the planet from the sky into the ground.

Cohn writes in The Distinction of Fiction that even in the case of nonfiction (which she calls texts that adhere to referential presentation, since they gesture toward some real-world event or phenomena, an assumption we can’t make with fiction), there is a space between the “I” who lives the story, the “I” who writes the story, and the “I” on the page, enacting the events. In essence, there is a kaleidoscope of selves orbiting around any given experience. The map cannot be the territory, Borges says in his short story. The map can never be the territory because the territory is the world itself; the map can only ever be that land’s mimetic rendering.

I had thought I was the marionettist, but I am the puppet woman. At least now I know I am a puppet.

Tom sends me an article in the Republican Eagle—Red Wing’s local newspaper—about the project’s construction. The article was published before the planets were placed in their spots, the very spots where, 20 years later I would find Saturn. From the article it is clear that the project is very much unfinished. At the time of the article’s writing, the Big Bang has happened but each planet in the solar system hasn’t yet taken its celestial place on stage.

The final line of the article is a student recalling the process of calibrating the center of the fictional solar system. “I’ve never seen a sundial before,” the students says. “They actually work.”

In June of 1999, I would have been younger than him, just about to turn thirteen. In 1999 I, too, had not seen a sundial—indeed, hadn’t seen one until I saw the very one he’s making in this photo, coming to me 25 years later, nearly to the day. I think then of modernity’s ability to rip me from the world around me, among me, within me, the world of which I am composed.

Which brings us to now. The puppet woman book will come out soon and I don’t know which—if any—real human beings will hold that book in their hands or read it on their screens. This is the magic of writing, of course: that you cannot know to whom you are writing because those readers might be people you never speak to or see, people you never get to know because they haven’t yet been born and will miss you and your time on this planet. This is the great irony of the professor’s proposal in Gulliver’s Travels: a language without language and only objects might be, admittedly, a more pure way to communicate in the present. But what about the past? It is speech and words that allow us to keep and correspond with all we’ve lost and are losing, with our private and shared histories.

“The gesture of closing is always sharper, firmer, and briefer than that of opening,” Bachelard says in the chapter of The Poetics of Space titled “House and Universe.” At the end of Gulliver’s Travels, Gulliver goes home but he is so transformed by his experiences, he becomes a recluse. At the end of Pinocchio, the puppet leaves his status as wood and turns to flesh, from mischievous, curious child to solemn and less interesting adult. At the end of the puppet woman novel—given how few people will actually read it, I’ll tell you now—time and space collapse until the woman, who has suspected she’s a puppet but not let herself know it fully, faces this reality.

“There were many lessons in this project,” Tom says in one of our most recent correspondences, and I think: present tense. Substitute “were” for “are.” There are so many lessons in this project. Dear Tom. You cannot know.

The lesson he highlights most is that the students “came away with a greater understanding of our place in the universe.”

That. It is only and always that. From Tom’s students’ hands in 1999 to my heart in 2019 to your eyes reading this story right now, possibly in 2024, maybe in some other future year.

“To use a magnifying glass is to pay attention, but isn’t paying attention already having a magnifying glass?” Bachelard says. “The surest sign of wonder is exaggeration.” In The Distinction of Fiction, Cohn writes: “Novels present us with a semblance or illusion of reality that we don’t take in a conditional sense, but that we accept as reality so long as we remain absorbed in it.”

In Salt Lake City, the sun sets beyond the mountains. I think of the past, a series of perpetual yesterdays, governed by the sun. In Red Wing, Minnesota, where time is different—it is one hour earlier there, though that is, to some extent, a fiction—the creek is running, butterflies lingering along a wooded path. In Charleston, South Carolina, time is different—it is two hours earlier there—and the moon is controlling the tides. “The world is a nest for mankind.” Tom writes to me, “Don’t go away.”

Dear Tom: I hope not to. I am trying to amplify that which surrounds me. I am trying to pay attention.

__________________________________

The Avian Hourglass by Lindsey Drager is available from Dzanc Books.