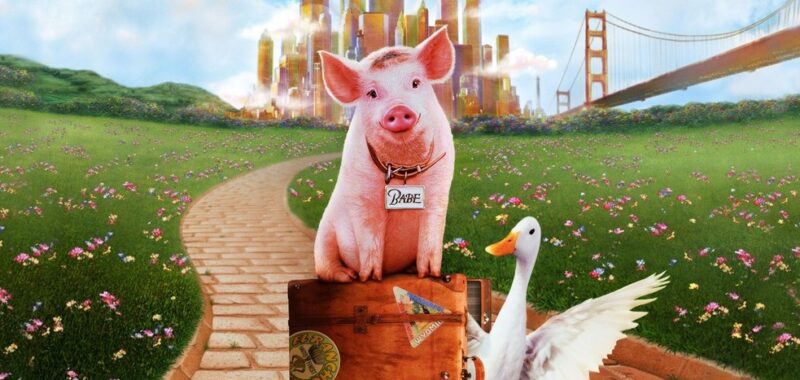

Babe: Pig in the City

(1998)

Article continues after advertisement

Director: George Miller

Studio: Universal

Budget: $90M

US gross: $18.3M

“But fate turns on a moment, dear ones, and the pig was about to learn the meaning of those two cruel words of regret: ‘if only’…”

–Roscoe Lee Browne as the Narrator

*

Farmer Hoggett (James Cromwell) gets maimed three minutes into Babe: Pig in the City, in a scene of horrifying physical trauma which tosses him to the bottom of a well, 6 foot 7 inches of kindly, shattered bones. So rapidly are the bucolic charms of the first Babe (1995) overridden by a base note of “harrowing nightmare” that my radar pings immediately for a pet favorite genre—“family films that might require therapy even for the adults watching” (see also Return to Oz, and Nicolas Roeg’s 1990 version of The Witches).

It is instantly, threateningly clear that we’re in for a George Miller movie, rather than a cozy sequel to Chris Noonan’s adorable sleeper hit, which Miller cowrote and produced. Thanks to the creative freedom Universal semi-accidentally gave Miller from the other side of the world, this one was likely to be at least 50 percent a Mad Max film revolving around a talking pig. It was going to be savage.

I paid to see it twice as an undergraduate in December 1998, agog at the film’s spine-tingling perversity, Miller’s frequently astonishing staging, and the blunt homage midway to the ghetto raid from Schindler’s List. I took friends. The way I remember it, seats clattering as entire families fled the movie formed an integral part of the soundtrack. I remain in awe of many things about it.

If Babe’s a round hole, with its human-porcine teamwork, Pig in the City is far too square a peg to get away with the pretense that it’s about the same things.

That mishap in the well serves notice: this film is going to be about mortality and happenstance, the cruel quirks of being alive, and trying to stay that way. (The Mad Max: Fury Road slave bride played by Rosie Huntingdon-Whiteley, who loses her foothold for that one irreversible moment, can surely relate.) Short of hanging “Beware!” signs around Babe’s neck with barbed wire, Pig in the City could hardly forewarn us more directly that it’s heading to some dark places.

Audiences, unfortunately, felt very much forewarned—in most cases, before they’d even bought a ticket. People tend to sound surprised when I tell them it flopped. In the US, it performed so dreadfully that Universal’s top-tier management was gone by Christmas. However badly they muffed up the release, and despite the emergency cuts it suffered, we owe them a debt of gratitude that the film even exists, in its trippy, rebellious, admittedly uneven form.

What seems hard to believe is that Universal had no idea what they’d paid for—at triple the cost of the first film, to boot. Noonan’s adaptation of Dick King-Smith’s beloved 1983 novel The Sheep-Pig was a runaway hit of rare perfection, which absolutely no one had a bad word for. Babe remains one of very few family-targeted films ever to score a Best Picture nomination, rightly won the Best VFX Oscar, and was nominated for five others, including Best Director for Noonan and Supporting Actor for Cromwell.

The next year, Universal commissioned a sequel, which Miller set to writing from scratch, with the eventual help of Judy Morris and Mark Lamprell. Noonan was out—amid something of a feud with Miller over who deserved creative credit for the first one. “The vision was handed to Chris on a plate,” Miller griped, while Noonan felt his own contribution had been undervalued. Cromwell even had to step in during Babe’s shoot to cool down an altercation. “Chris’s humanity and his heart and his sweetness, his vision, was really imprinted on the way he shot that picture,” the actor would recall 25 years later. “George thought there should be more edge [to Babe]. What he wanted was more like It’s a Wonderful Life. [And it got] darker, and darker, and darker.”

Universal kept faith, blindly, that Miller would deliver something they could promote. The whole production was outsourced once again to Sydney, on soundstages at what was then called Fox Studios Australia; Hoggett’s farm had to be built anew, because no one had expected Babe to be such a hit. “We won’t tear it down so quickly this time,” remarked the production designer Roger Ford, rather tragically. (There has never been a Babe 3.)

Forget the 1,200 extras, 600 crew members, and 50 animal trainers. Getting 799 animals to work together, in close quarters, for ten months was always going to be the hard part. These included 80 pigeons, 100 pigs, 130 cats, and 120 dogs, more than half of which came from dog shelters around Sydney, and were subsequently rehoused by members of the crew. (Miller took home a chihuahua.) The half-dozen mice who serve as a Greek chorus, trilling out Edith Piaf’s “Are You Lonesome Tonight?,” kept breeding like crazy—there were more than a hundred within weeks, until their friskier tendencies were somehow curbed. No one had any idea whether chimps could get along with pigs, until they gave it a whirl.

Mutterings later from the high-ups at Universal, that Miller had swanned off with a small fortune and taken them for a ride, make them come across as somewhat myopic—or just poor readers. Merely to describe the plot undoes their case. According to Miller, the shooting script had everything in it that would later cause conniptions. There’s the near-drowning of a bull terrier (voiced like a Brooklyn hoodlum by Stanley Ralph Ross), the flapping distress of a goldfish flung from its smashed bowl, and the pushing-up-daisies experience of a disabled Jack Russell named Flealick (Adam Goldberg), a chatty fellow with his own little wheelchair, who has a dangerous obsession with clinging onto mudguards by his teeth.

These and many other non-farmyard animals are met by Babe (voiced this time by squeaky-croaky E.G. Daily) when he finds himself stranded in the big city, at a woebegone boarding house beside a neon-lit canal. With Arthur Hoggett bed-bound, his wife Esme (Magda Szubanski) has hatched a desperate plan to save their farm from foreclosure with “the wee pig” in tow. But a sniffer dog at the airport raises a ruckus; Esme is humiliatingly strip-searched before being thrown in jail; in all these ways, their money-raising scheme comes unstuck. In the scary urban jungle, Babe gets room and board only thanks to the charity of pencil-like, jittery landlady Miss Floom (the Modiglianiesque Mary Stein, who’s delightful—her every utterance a question squeezed out between adenoids).

In this one-size-fits-all metropolis, we espy the Sydney Opera House, Big Ben, Christ the Redeemer, and the Eiffel Tower all poking out of the same cramped skyline. “This is all cities,” as Roger Ebert put it in his rave review. (Ford’s maximalist set design has hints of Brazil, Blade Runner, and Jeunet-Caro’s The City of Lost Children (1995), mashed together into a composite J.G.Ballard might have cherished.) While the curtains of snooty opera fans twitch from facing houses, Miss Floom has been a Samaritan on the down-low, taking in the city’s starving strays out of the kindness of her heart.

To be fair to Universal’s execs, there’s a great deal in Miller’s vision that the script alone could never have betrayed, including a level of characterization that’s disturbingly brilliant—funny and poignant at the same time, owing not just to the animal casting (and nonpareil wrangling), but the voice casting, too.

There’s a homeless pink poodle (Russi Taylor, wondrous) whose every line is a Blanche DuBois sob story: “Please, sir. Please. I know you’re different from the others. Those that had their way with me make their empty promises, but they’re all lies—lies!” The family of chimps indoors, with their string vests, hair ties and bubblegum, are typed in their turn as salt-of-the-earth slum lodgers. That’s the late Glenne Headly as warmhearted Zootie (“You gotta praablem, sweetie?”) and stand-up comic Steven Wright as her lugubrious bloke Bob, a shady customer given to philosophical musings on life (“It’s all illusory: it’s ill and it’s for losers…”).

As for Miss Floom’s Uncle Fugly, played with zero dialogue and unkempt clothes you can practically smell by a then-seventy-six-year-old Mickey Rooney, he’s fugly, all right. If you found him hanging around the festering apartment complex in David Lynch’s Tinseltown death-dream Mulholland Drive (2001), he’d be right at home. In the non-Lynch context of a family blockbuster sequel, he’s all the more hellish as a joyless clown, genuinely grotesque in his full getup for “the Fabulous Flooms,” with a giant egglike dome and pink candy-floss hair poking out.

We don’t get a lot of Rooney at all—his scenes became especially vulnerable at the cutting stage, when executives finally clapped eyes on what Miller had put in the can. Still, what’s left of him is distressing enough. His butler, the still center of this vortex, is a very special Bornean orangutan named Thelonius (laconically voiced by a Scotsman, James Cosmo), who gravely looks down on the madness from a stained-glass clerestory, passing silent judgment. The camera is mesmerized by his doleful, unblinking face.

You can’t stop trying to intuit what he’s feeling—say, when Babe trips Fugly up by mistake, causing havoc during the Flooms’ circus act in a children’s cancer ward. This is not what you’d call slapstick havoc. A fire breaks out, the traumatized chimps run for cover, the sprinkler system kicks in, and Uncle Fugly’s life’s work collapses in tatters. He and Thelonius stare back, shell-shocked, at the aftermath, in a slo-mo reaction shot that has a godforsaken poetry.

It’s amazing, gratifying, and kind of hilarious that as much of this survived as it did. Clearly, Miller provided so little cuddly stuff for the studio to fold in, they simply had to put up with much of what they were given—that is, once they’d finally persuaded him to show it to them and their families. A focus-group screening in Anaheim Hills, on November 8, 1998, went horribly with children—as you can well imagine—and the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) also came back with a PG certificate, which seems positively mild when you hear about what Miller’s original cut had in it.

Viewers of this even-darker version would have been treated, for instance, to a full scene of Esme being strip-searched—reduced, in the end, to the sound of a latex glove being snapped on by her tormentor. Ferdinand the duck barely escaped a chef’s cleaver turning him into Chinese takeaway. Rooney had a deathbed scene and numerous others too disturbing to see the light of day.

It could have been much worse. In early drafts of the script, Farmer Hoggett was actually supposed to die at the bottom of that well. One of the nosy neighbors was originally murdered by Esme and Miss Floom as comeuppance for being a snitch—a beyond-dark punch line they actually shot, but sensibly jettisoned early on.

Plenty more had to go, though. Babe nearly got pushed into the fire during the hospital inferno, until that scene was rejigged; he was also sadistically tricked by the chimps into clambering up a pyramid of junk and tumbling into the canal—yet another scene featuring Rooney that was binned outright. When the animals are impounded, there were rabbits smoking cigarettes, hair products being tested on cats, and all sorts. “That’s a vivisection laboratory,” as Cromwell recalls. “There [were] animals with posts drilled into their skulls and sores, cancers, it was—oh my God.”

It shouldn’t be funny. Imagine the faces of Casey Silver, then chairman of Universal Pictures, and his boss Frank Biondi Jr., when they beheld Babe’s entire life flashing before his eyes in near-subliminal flickers, as the narrator asks us to ponder his relentless pursuit by scrapyard dogs and, by extension, the senseless cruelty of the universe. “Something broke through the terror—flickerings, fragments of his short life, the random events that delivered him to this, his moment of annihilation.”

That bull terrier, dangling off a bridge by his studded collar, jerking out his last breaths. The goldfish, flapping and helpless. These are moments that actually made the final cut—the drowning of the dog, per Cromwell, was shot using an animatronic puppet and massively cut down, but as he rightly says, “It’s still pretty harrowing.” Just before Flealick goes to heaven, one wheel on his overturned chair squeaks out a final few rotations, before grinding to a pitiful halt.

That might be Miller’s most profound image—his answer to life’s brief candle sputtering out. But it’s soul-scarring. Did no one spot that his film’s whole middle act was an immigration parable, Dickensian in its pathos, crossed with Animal Farm? The excluded, the outcast, all find shelter in a sanctuary that’s a long way from utopian—the only food’s jelly beans. Cats and dogs are on the verge of hostilities. And then it’s round-up time. The Gestapo-like raid on the boarding house (after a tip-off from the neighbors) also had to be trimmed down into less harrowing form, so the film could at least look like wholesome family fare.

The MPAA did finally come back with a G rating—heaven knows how. But the alley cat was out of the bag. The schedule for recuts was worsened by a sound glitch: the entire film was “an assault on the ears,” according to Miller, because of an overly loud mix that had somehow passed muster in Australia. To fix the problem, Universal’s dubbers supposedly had to work 20-hour days against the clock. They had no choice but to cancel a benefit premiere, scheduled for November 15, while the work was done—and after this announcement reports started to leak out far and wide that the film was a problem child undergoing a severe remedial program. (This was surely, partly, true.)

It’s hard to know how a film as perverse as this could have ended satisfyingly in a way that keeps faith with its themes.

Days before this, Universal’s parent company Seagram fired Biondi, the overall head of its entertainment division. Babe’s unfinished state and a string of other underperforming films were factors, but the most obvious trigger for his departure was the brand-new failure of Meet Joe Black—the three-hour long, $90M romantic drama starring Brad Pitt as Death, which had just opened to baffled reviews and a dud, third-place opening weekend. Pressure only intensified on Babe, and on Silver, who was hanging on to his own position by a thread.

By the end of the month, he was gone, too. Pig in the City’s Thanksgiving release slot might have looked like prime real estate a year before, but November had since filled up with the most brutal competition possible (except Meet Joe Black, of course). Delaying the release wouldn’t work, because the trailers, ad spots, and cross-promotional tie-ins were all cued up.

Pixar’s A Bug’s Life went on wide release right at the same time, and was instantly massive, grossing nearly triple in a week what Babe would achieve over its entire stateside run. Coming in second was Paramount’s The Rugrats Movie, out a week already, and gobbling up even more of Babe’s core audience. Babe crawled in fifth—a miserable result Silver couldn’t escape from, and very much the kind of high-profile flop that makes studio regime change a foregone conclusion.

*

I still love the film. (So does Tom Waits.) If we’re picking holes, I’ve never been wild about Miller’s climax at a hospital ballroom gala, with Esme strapped into the late Fugly’s clown suit and swinging about on a chandelier—it’s a descent into boisterous Roald Dahl slapstick that doesn’t give Babe himself nearly enough to do. It’s hard to know how a film as perverse as this could have ended satisfyingly in a way that keeps faith with its themes, but this is too much of an abdication toward generic hoopla.

“That’ll do, pig” from Farmer Hoggett was the first film’s motto, but when it’s trotted out at the end here, with Babe safely back at the farm, it plainly doesn’t work. Our pig’s various acts of kindness, such as saving the bull terrier and goldfish from near-certain death, have gone without human notice at any stage. If Babe’s a round hole, with its human-porcine teamwork, Pig in the City is far too square a peg to get away with the pretense that it’s about the same things. It’s about other things instead—mainly, the heroism of lending a hand when there’s no one watching.

None of these considerations caused it to flop, though. Beyond the poorly planned release and too-late flurries of studio panic—over legitimate issues that ought to have been addressed far sooner—it conveys so little desire to mollify its intended audience that they blatantly smelled a rat. Particularly in the US, newspaper reports raising eyebrows at lofty ambitions (“Felliniesque,” “much darker in tone”) rarely fail to put off wary consumers, who paid more attention to the bad press hounding the film than the decent clutch of impassioned reviews. It fared better abroad—but not nearly well enough to erase the taint of a serious failure.

Miller has barely talked about it ever since. Further setbacks stalled him—the planned shoot of a fourth Mad Max in 2003 was aborted by Warner Bros., because the US dollar had collapsed after the Iraq War, and security concerns made shooting in Namibia too dicey. In the meantime, Mel Gibson went down his own fury road and was written out of the franchise. Miller pivoted to Happy Feet (2006)—the one about dancing animated penguins—thereby regaining faith that he could be trusted again with family entertainment. But that film’s 2011 sequel repeated Babe’s pattern by, yet again, flopping; he would be stung again by the underperformance of Furiosa in 2024.

Sequels are expensive: everyone involved demands more money, and you need an airtight vision to stop audiences feeling jaded. Miller had an astonishingly clear one for Mad Max: Fury Road (2015) by the time that got off the ground, but the production was still chaos, and could easily have resulted in a ruinous turkey with cult appeal only. His next one, Three Thousand Years of Longing (2022), landed in that terrain—an archetypal passion project cum folly that essentially set fire to $60M on an auteur’s whim and took a bow. Even Fury Road wound up costing so much it barely broke even, but it staked its rightful claim as the action blockbuster of the decade, and the fan worship more than compensated.

Miller keeps charging on, in pretty fearless pursuit of doing things his own way. He reminds me less of Babe than the intimidating bull terrier, who openly admits, “A murderous shadow lies hard across my soul.” Feel free to commiserate with the execs dishing out such foolhardy blank checks, but when the films soar—and scald—like this one, there’s almost no budget I’d wish to deny him.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Box Office Poison: Hollywood’s Story in a Century of Flops by Tim Robey. Copyright © 2024. Used with permission by Hanover Square Press, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.