It is conventional wisdom that novels are either plot-driven or character-driven, but I’ve long been fascinated with the way structure can drive a story. Structure is the vessel we pour our narrative into. It goes a long way to determining its shape. Unusual structures produce surprising novels. There’s nothing wrong with Freytag’s Pyramid, I suppose, but sometimes you need to flip the pyramid on its head or blow it up and build something else altogether.

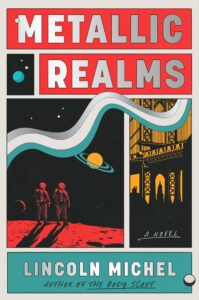

My fascination with structure became something of an obsession while writing my new novel, Metallic Realms, which is constructed as a series of faux-scholarly essays about a set of gonzo science fiction stories. Within this structure, the narrator reveals his own story as well as chronicles the rise and fall of the writing collective that wrote the otherworldly adventure tales. Metallic Realms is, among other things, an homage to Vladimir Nabokov’s Pale Fire—a novel that rewired my understanding of the possibilities that structure can open in a text. Pale Fire is famous enough that I don’t need to recommend it here—although if you haven’t read it, do so now!—but below are ten more novels I love that will expand your understanding of structure and therefore the possibilities of fiction.

*

Dictionary of the Khazars: A Lexicon Novel by Milorad Pavić (translated by Christina Pribićević-Zorić)

I may as well start with the most formally bizarre novel that you will ever encounter. Pavić’s 1984 novel, Dictionary of the Khazars, has no plot or characters in the traditional sense. Instead, the book consists largely of three different and contradictory dictionaries: The Red Book (Christian sources on the Khazar question), The Green Book (Islamic sources on the Khazar question), and The Yellow Book (Hebrew sources on the Khazar question). The novel was inspired by the real history of the Khazar people and their conversion to Judaism in the 8th century. It also serves as an exploration of countries and peoples that sit at the crossroads of rival powers, such as Pavić’s own native Yugoslavia. If the format of the novel wasn’t extraordinary enough, it also comes in both “male” and “female” versions that contain one slight yet significant difference.

The Vegetarian by Han Kang (translated by Deborah Smith)

Kang, the most recent recipient of the Nobel Prize in Literature, made her name in America with this book about a woman who decides to stop eating meat and then becomes increasingly distanced from her family, Korean society, and humanity writ large. It’s a lovely and dark dream of a novel. And it’s unusual structure helps enhance the themes. The novel is written in three parts, each from the POV of someone other than the central character, allowing the protagonist to remain a mystery to both the characters and the reader.

The Fifth Head of Cerberus by Gene Wolfe

Gene Wolfe is my go-to recommendation for readers who don’t believe that science fiction can be as stylish, complex, and narratively inventive as so-called “literary fiction.” His best work is probably the Book of the New Sun series, but The Fifth Head of Cerberus is a great introduction to his melding of mind-bending SFF concepts and high literary style. The setting is a pair of sister planets far off in space. The story is filled with mad scientists, shape-shifting aliens, robots, and other classic science fiction concepts. But the narrative is, in addition to being beautifully written, unusually structured. Like The Vegetarian, the novel is three novellas. The novellas are written in very different styles and each successive part subverts and complicates our understanding of the preceding one(s).

My Lesbian Novel by Renee Gladman

The most recent entry on this list, Gladman’s 2024 novel is both the titular lesbian romance novel and a novel about writing that novel. The main narrative of the book is a conversation between an interviewer named “I” and the authorial stand-in “R” as they discuss R’s struggles with writing a lesbian romance novel. Passages from the novel-in-progress are excerpted throughout the conversation, which I and R dissect and debate. It’s a fresh and surprising structure that allows Gladman to comment on genre, writing, love, and much more.

If on a winter’s night a traveler by Italo Calvino (translated by William Weaver)

There are many Calvino novels that would fit on this list, especially the works written after the protean author joined the Oulipo group in 1968. The Oulipians were dedicated to using unusual constraints to generate new types of literature. Calvino’s Oulipian era produced books like Invisible Cities (a novel composed of descriptions of fictional cities) and The Castle of Crossed Destinies (a novel structured around tarot cards). But the most formally fascinating Calvino novel from this period must be If on a winter’s night a traveler. The novel has a braided narrative. One part follows the second-person POV adventures of you, the reader, as you try to read Calvino’s new novel. The other half is a series of first chapters of different novels, each written with their own Oulipian constraints. The result is wild, audacious, and one-of-a-kind.

Life: A User’s Manual by George Perec (translated by David Bellos)

Speaking of Oulipian writers, George Perec is perhaps the epitome of an Oulipian writer using a variety of bizarre constraints to generate highly original works. Most famously, his novel La disparition (or A Void in English) was written entirely without the letter “e.” But his most structurally unique novel might be Life: A User’s Manual, which is a series of interlinked stories taking place in a single apartment block. The order of the stories was derived by imposing the knight’s tour—where a knight piece moves around the chessboard without touching the same square twice—on top of a grid layout of his fictional setting.

Erasure by Percival Everett

Everett has long been one of America’s great yet underread living writers. Thankfully, the underread part has started to change with the release of his bestselling (and National Book Award-winning) novel James as well as the film adaptation American Fiction. For those looking to dive into Everett’s stellar back catalog, there’s no better place to start than Erasure. Even if you’ve seen the American Fiction film, you probably won’t be prepared for the scathing satire of the novel that includes an audacious parody-novel-within-a-novel that stretches for nearly 70 pages in the middle of the book.

Why Did I Ever by Mary Robison

Mary Robison’s Why Did I Ever is a hilarious and moving mosaic novel composed of over 500 fragment chapters. While many fragmented novels exist today in our social media scrambled age, Robison wrote hers in 2001, long before Twitter and TikTok existed. Robison is often associated with the “Kmart Realism” writers like Raymond Carver who wrote realist stories in minimalist prose. Why Did I Ever is a great example of how inventive structures can be applied to any genre, including literary realism. Robison has said the draft of the novel was originally written on notecards without any organization, which shows how structure and composition can align.

The Story of My Teeth by Valeria Luiselli (translated by Christina MacSweeney)

Another novel where the composition shaped the structure is Luiselli’s excellent 2013 novel The Story of My Teeth. Following the story of auctioneer and raconteur Gustavo “Highway” Sánchez Sánchez, the novel’s chapters leap around in subject and style. One chapter consists of descriptions of stories about famous historical figures’ teeth, for example. The novel’s unusual form is shaped by the even more unusual circumstances of its creation: Luiselli wrote the work in conjunction with workers in a Jumex juice factory in Mexico. Luiselli would send a chapter for the workers to read, who would send feedback that Luiselli would then use to write the subsequent chapter.

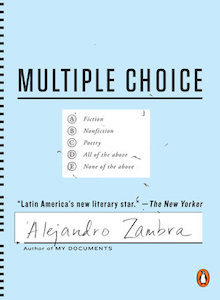

Multiple Choice by Alejandro Zambra (translated by Megan McDowell)

I’ll end this list with one of the most unclassifiable works I’ve had the pleasure of reading. Zambra’s Multiple Choice is a novel (or is it a novel?) that is shaped like the Chilean Academic Aptitude Test. Basically, the Chilean version of the SAT. This means there is a chapter of Sentence Completion questions and another of Reading Comprehension questions. Somehow, Zambra is able to pull humor, pathos, and lyricism out of these extreme constraints. While I’m calling it a novel, the English translation cover itself hints at the unclassifiable nature of the work. The cover shows a set of multiple-choice answers: “(A) Fiction (B) Nonfiction (C) Poetry (D) All of the above (E) None of the above.”

__________________________________

Metallic Realms by Lincoln Michel is available from Atria Books, an imprint of Simon & Schuster.