STANFORD, California — Some of the first artworks I encountered when I visited Spirit House were doors. Installed along an outer wall of the Cantor Arts Center, James Clar’s wooden door is etched with motifs commonly found in the Philippines. A programmed LED light along the bottom gap makes it appear as if people are walking past, though, of course, the door is just a facade. Similarly, Do Ho Suh’s “Doorknobs: Horsham, London, New York, Providence, Seoul, Venice Homes” (2021), a collection of delicate door handles sewn from colorful translucent fabric, are based on ones found in his previous residences. The handles have been divorced from their original function and are too delicate to touch. Both these pieces deny passage while hinting at a presence beyond what is seen: the illusion of passersby in Clar’s door and the memory of previous spaces in Suh’s.

The artists in Spirit House, organized by Stanford University’s Asian American Arts Initiative, grapple with being denied passage, instead caught within the personal, family, and global stories of the Asian diaspora, and within the intellectual cul-de-sac of racial identity. These works are all spirit houses, as they manifest the ghosts that haunt Asian Americans and, in doing so, learn how to live beside them.

In popular culture, ghosts are portrayed as being between worlds, often because something in their past remains unresolved. Asian Americans know a little something about being in between, and we remain a spectral presence in American racial discourse, never quite injured enough to warrant serious discussion. Even when Asian Americans are the target of explicit violence, as in the 2021 Atlanta spa shootings, we spend inordinate amounts of energy trying to convince others that there is, indeed, still racial discrimination against Asians. Or we are a wedge used to further oppressive structures, as seen in the recent dismantling of affirmative action.

In her groundbreaking 2001 book The Melancholy of Race, Anne Cheng used Freud’s concept of melancholia to examine how American racial discourse remained mired in a state of unresolved grief, and how the country’s collective obsession with racial grievance centered the conversation on “getting over race” rather than on figuring out how to properly grieve. The artists in this exhibition know that we cannot simply “get over” the history and process of racialization, as well as the destructive, intergenerational wake left by US imperialism and militarism in Asia. They seem instead to ask: How do we grieve, understand, honor, and ultimately live with these ghosts?

Many of the artists in Spirit House have family stories that are intimately connected with one of the several collective traumas experienced by Asians and Asian Americans in the last century. The central structure in Greg Ito’s “The Weight of Your Shadow” (2023) is a small building that evokes the barracks where Japanese Americans, like Ito’s grandparents, were incarcerated by the United States during World War II. The building is surrounded by family heirlooms from the artist’s grandmother and placed on a reflective blue surface. In the work viewers literally see themselves alongside Ito’s history, showing how our own identities are braided together with the stories of our families, communities, and ancestors.

Kelly Akashi’s bronze and glass casts of her own hand wear her grandmother’s jewelry or hold natural elements such as twigs, stones, or pinecones scavenged from Poston, Arizona, the site of a detention camp where the artist’s family was incarcerated. According to her research, many of the pines that stand today were originally planted by some of those incarcerated Japanese Americans, and they serve as solemn monuments to a painful history. Akashi’s colored glass sculptures, such as “Inheritance” (2022), seem to glow, as if this act of casting can transform her physical body into a spirit in order to reach across time to touch this moment in her family’s history.

Jarod Lew’s photography series In Between You and Your Shadow is based on Lew’s discovery as an adult that his mother was the fiancé of Vincent Chin. Chin’s brutal and racially motivated murder and his murderers’ light sentencing galvanized and reshaped the Asian American community. Lew’s mother agreed to be photographed on the condition that her face be hidden, and through a series of light flares and compositional moves she becomes both the subject and a ghostly, unknowable presence in these photographs — refusing to be used as a political symbol. Instead, she asserts her right, and that of minoritized individuals and communities, to invisibility.

A touching and at times hilarious installation by Heesoo Kwon also negotiates themes of selective visibility. Kwon inserts avatars from her fictional feminist religion into childhood photographs and family videos. The avatars are only visible when viewing the images from a certain angle, which can make visitors question whether or not they actually saw them. By retroactively inserting these images into decades-old photos and videos, the artist perhaps recognizes that these protective spirits were always there, guarding Kwon and the women in her family, or she uses them as a way to grieve a life that could have been.

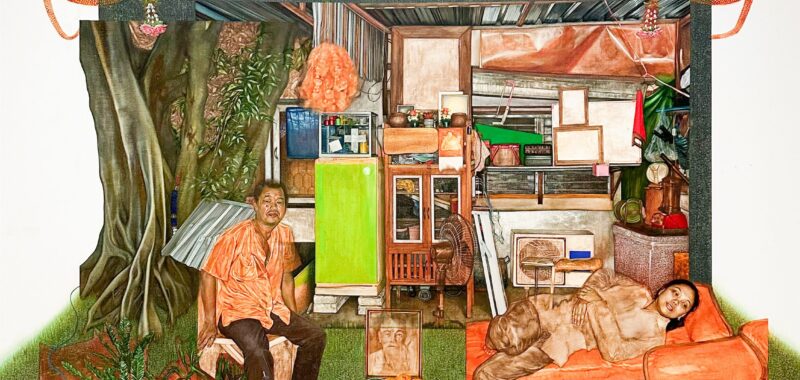

One the show’s highlights is a painting by Nina Molloy featuring detailed depictions of her great-grandfather, grandfather, and mother, each appearing in various states of translucency. It combines the density of Dutch altar painting, the flattened perspective of Korean chaekgori painting, and the structure of a Thai spirit house in its dollhouse-like composition. Replete with representations of objects, materials, and decorative items that would commonly be found in Southeast Asia, the monumental scale and hyperrealistic rendering of this masterful work stirs a feeling like religious ecstasy. This painting represents the exhibition’s central conceit, that art can collapse time, ideas, and memory. Just as one makes a spirit house in Thailand before beginning construction to honor and shelter the local spirits, the artists in Spirit House show us that art is a way to construct meaning and make sense, a way to understand, grieve, and ultimately care for the myriad collective and individual spirits that have shaped the Asian diaspora.

Spirit House continues at the Cantor Arts Center (328 Lomita Drive, Stanford, California) through January 26, 2025. The exhibition was curated by Aleesa Pitchamarn Alexander, Robert M. and Ruth L. Halperin Associate Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art and Co-director of the Asian American Art Initiative at the Cantor Arts Center, with Kathryn Cua, curatorial assistant for the Asian American Art Initiative.