BERLIN — I first encountered Pia Arke’s video “Arctic Hysteria” (1996) in 2021 at the 34th São Paulo Biennial. In it, the Greenlandic-Danish artist crawls naked across a large black and white photograph of the Arctic landscape before tearing it up. Her hypnotic work invites comparisons with artists such as Ana Mendieta; both used their bodies in performances and films to reflect on both their countries’ violent colonization and women’s bodies as an oppressed other. Poised at the intersection of feminism, post-colonialist critique, and ecology, Arke’s art, spanning the 1980s to the early aughts, is lesser known internationally, but it’s been recognized in Nordic art institutions since her death in 2007.

Comprising over 100 works, Arctic Hysteria at KW Institute for Contemporary Art is her first posthumous retrospective outside Denmark, organized by KW with John Hansard Gallery in Southampton, England. Curator Sofie Krogh Christensen frames Arke’s practice as addressing the contrast between Denmark’s colonialist narratives, characterizing the invaders as benign, and the lived experience of colonization marked by invisibility and ethnic stereotypes. As Ros Carter writes in the catalog, when Arke first began to make art, “it is questionable as to whether Denmark even regarded itself as having been a coloniser in the same sense as other countries. Instead, it was, and still is, a common belief within Denmark that its relationship with Greenland was based on a softer, more sympathetic and benevolent form of colonisation.”

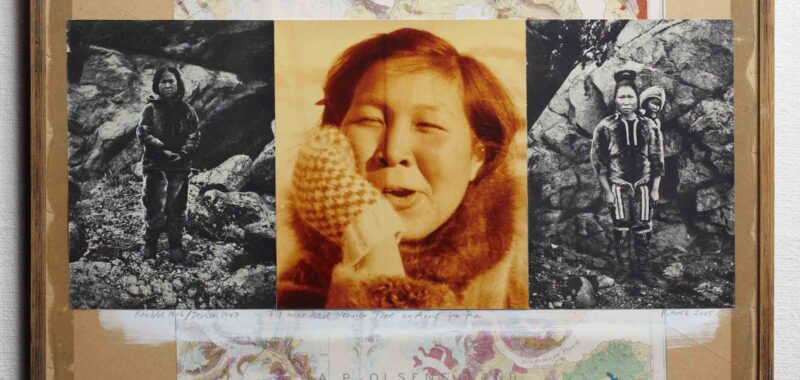

Arke’s works pierce this fantasy. For instance, her collages of old photographs in the series Arctic Hysteria IV (1997) alternate photos of unidentified and unclothed Greenlandic women with those of named and fully clothed White explorers. A work in another collage series, Legend I–V (1999), for which Arke layered photographic portraits over Western researchers’ maps of Greenland, incorporates an old picture of Arke’s Inuit mother (her father was Danish) and another young woman smiling alongside a White man. It’s this kind of propaganda that, as artist Tiara Roxanne notes in her catalog essay, the Danish government used to justify the forced urbanization of Inuit people — as well as the destruction of their livelihoods and traditions — as modernization.

The complex role of science in legitimizing imperial conquest, as colonizers manipulated it to rationalize their means and ends, is a recurring motif in Arke’s work. It informs her various photographic series picturing ethnographic books, juxtaposing the books’ musty, sumptuous allure — the photos convey their physical heft and beauty — with the racist ideas that these often scientific books contain. The resulting aesthetic and cognitive tensions are but one example of what Roxanne calls Arke’s many “archival ruptures.” Similarly, the whimsically titled “May Only Be Touched with Thumb and Little Finger” (1999) depicts a book as a staggered tower of paper on the floor, rising perilously high.

Arke’s haunting series Nature Morte alias Perlustrations I–X (1994) intercalates black and white images of scholarly texts by Arctic explorers with portraits depicting subjects such as an extended forearm, a childhood toy dog, and a close friend, the friend also shown with Arke and her cousin in the photographic quadriptych “The Three Graces” (1993) and alone in “Perlustrations (Susan Mortensen in Clinic)” (1994). In Nature Morte, a closeup reveals the corrugated scarring from Mortensen’s mastectomy. “Perlustrations,” in which Mortensen poses in motion, with and then without white gloves — which could allude to her surgery — is particularly eloquent. In these deeply personal works, Arke stresses the gestural power and vulnerability of actual women’s bodies, contrasting them with the discursive bodies in her images of books embodying scientific knowledge.

The exhibition also sheds new light on the video after which it is titled by including an archival source: a photograph of a distraught Inuit woman, naked from the waist up, restrained by two White explorers. In 1995, the Explorers Club in New York denied Arke the right to reproduce the image, citing its “sensitive” (in their words) nature; a fax from the club is displayed in a glass vitrine alongside a copy of the photograph. Arke’s bold interventions pick up on the early definition of the term “hysteria” in psychoanalysis, dating back to Freud and Charcot, as a quintessentially female condition. The artist exposes it as a chauvinist, colonialist construct by drawing viewers’ attention away from medical terminology and back to the historical and geographic context that shaped it.

Arke’s project of archiving her Inuk lineage later in her career was cut short by her death from cancer at age 48. Some of the show’s final galleries are devoted to numerous photographs and stories that she collected while revisiting the area where she was born and other Greenlandic Inuit regions. She published these in her book Stories from Scoresbysund (2003), some of whose pages are exhibited as a single sprawl. Her impressive quest to create an archive harks back to her earliest photographic series. For Imaginary Homelands alias Ultima Thule alias Dundas ‘The Old Thule’ (1992/2003), she captures Greenlandic home construction with a pinhole camera. She also made works with a camera obscura that she built so she could fit inside of it as if inside a house (a replica is on view). In “Self-Portrait” (1992), for example, she poses naked against Greenlandic landscapes. These late and early works, which together compose an archive that’s both intimate and communal, trace Arke’s desire not simply to call forth memories but rather to reinscribe them with the reality of the body against its representation by White colonizers. While questioning the historical tools of archiving, she also re-anchored it in actual physical bodies — starting with her own.

Pia Arke: Arctic Hysteria continues at KW Institute for Contemporary Art (Auguststraße 69, Berlin, Germany) through October 20. The exhibition was curated by Sofie Krogh Christensen with curatorial assistance from Aykon Süslü.