ROSWELL, New Mexico — The smelt fish finally arrived at the Smith River this year, in late July.

Earlier in the month, Dominick Porras had messaged me with a seasonal update: “In my recent journey up north, there was nothing [no people], due to the absence of the fish this year. Which has become increasingly random with each anticipated harvest.” The importance of their arrival, and the ensuing harvest, was all the more palpable after I visited Porras’s exhibition at the Roswell Museum, Silvery Synthesis, which includes black and white photographs of the fish and the Bommelyn family of Tolowa Dee-ni’ in California, who continue the traditional practice and methods of drying smelt.

Porras is an interdisciplinary Chicano/Coahuiltecan artist whose work is tied to his lived experiences of connection within communities and to nature — for instance, his reflection upon recurrences like that of the smelt’s journey to the Smith River. He literally and figuratively frames the exhibition with rasquachismo art, using abandoned silkscreen frames and film developer hangers, mirroring the resiliency of community and tradition he portrays in his images. The approach is one of resourcefulness and imagination, seeing value in that which has otherwise been abandoned or cast aside.

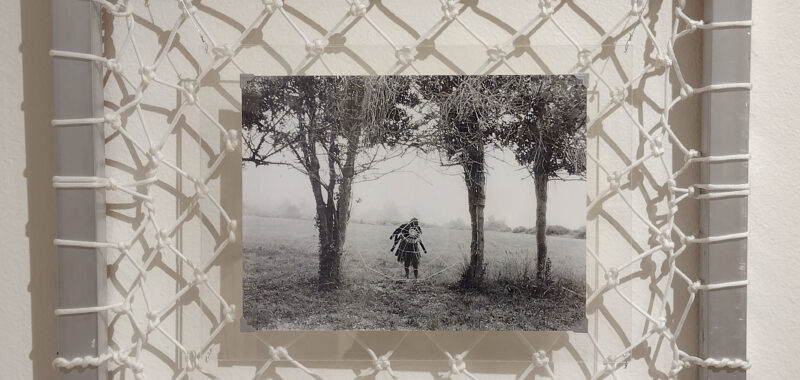

Texture, pattern, repetition, and practice combine with chance and the reality of climate change — will there be fish this year? — in Porras’s Da’-chvn-dvn series from 2023, five photographs that correspond to the number of bays used for drying smelt under the sun. The fish are arranged row by row, side by side, alternating head to tail on grass beds. It wasn’t until I examined installation images of the show that I realized the netting in the Da’-chvn-dvn works — attached to and stretched between all sides of each silkscreen frame, providing a support for the photos — is constructed with clover knots, countless wishes of good fortune. And with those knots, the artist forms a grid, bringing abstraction into the mix.

In addition to the photographs of the fish camp, Silvery Synthesis features images of a family burial in Texas and scenes from the Sacramento Valley. In particular, I haven’t been able to stop thinking about “Yaya and Madboy / Tehachapi Mountains” (2024). In the photo, the artist’s sister, Andrea Porras, dances in the Tehachapi Mountains of California with a sculpture of a buffalo ear made by Madelynn Boyiddle (Kiowa). Alone in an open field, she holds strings attached to the sculpture, reaching her arms up and out, with one leg stretched behind her. Bending at the hip, her body becomes parallel with the horizon as her other leg grounds her movement, maintaining a connection between the land and the sky. The photo is one of many portrait-like images framed in individual film developer hangers, arranged in parallel groups of four and displayed in stepped formations on the wall. Similar to the netting in the Da’-chvn-dvn series, the repeated pattern implies a structure of support — in this case related to images of family, surroundings, and personal practices, traditions, and rituals.

Also in the show is a grouping of Fallen Harps (2024), for which Porras again repurposed silkscreen frames, this time using guitar strings and pegs to create sculptures that double as musical instruments. By installing them alongside three-dimensional works made from 35mm film cassettes, paracord rope, and beads, the artist emphasizes how objects can be used for multiple purposes and brings together abstraction and rasquachismo, incorporating whatever materials are on hand.

As the title implies, silver plays a central role in the exhibition, the artist’s first solo museum show since graduating with his MFA from the Institute of American Indian Arts last year. As a chemical component of the developing process, silver gives analog photographs that classic shimmery quality. As a color and its variations, the silver of Porras’s frames, the black and white netting, and the gray shadows on white walls together visually cohere the show. Repetition is suggested throughout, and I can’t help but think of how silver is also used to create a mirror by coating glass, reflecting back to us the cyclical process of looking, forgetting, and remembering.

Dominick Porras: Silvery Synthesis continues at the Roswell Museum (1011 North Richardson Avenue, Roswell, New Mexico) through August 18. The exhibition was curated by Aaron Wilder, curator of Collections and Exhibitions.